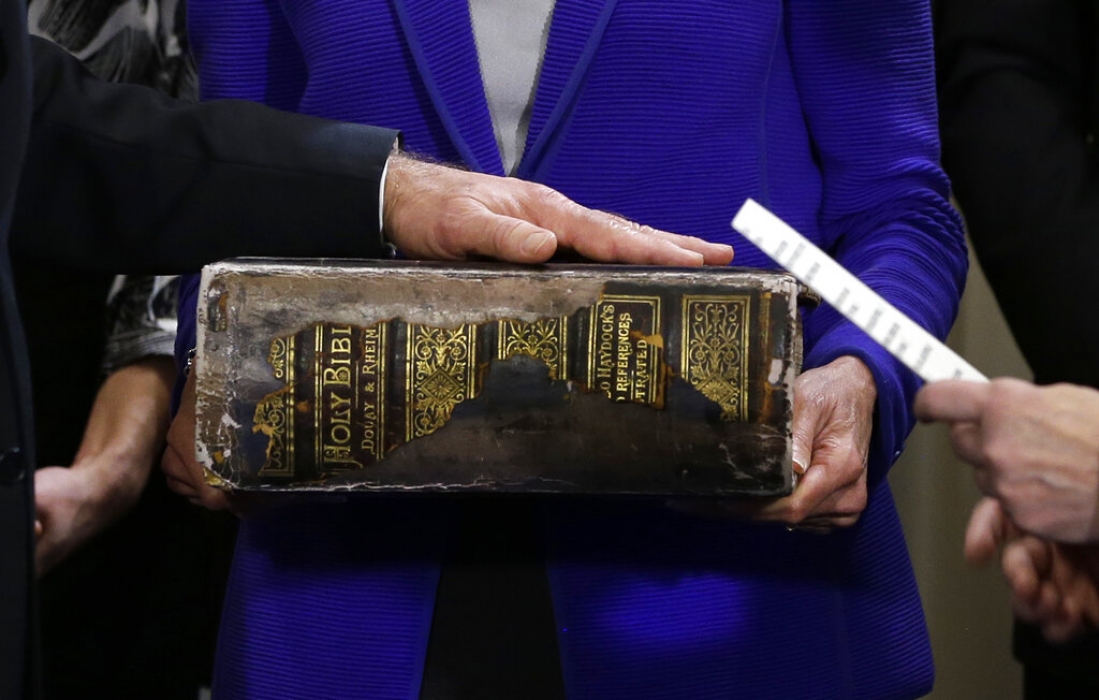

Following European custom, all 13 of the original American colonies required an attestation of religious belief or affiliation — a religious oath — as a prerequisite for an individual to hold public office.

These oaths were viewed as instruments of social control, given the traditional view that citizens were trustworthy as civil servants only if they were willing to affirm their allegiance to basic religious tenets. It was not until a U.S. Supreme Court decision — Torcaso v. Watkins (1961) — that such religious tests were invalidated at the state level as violations of the First Amendment’s free exercise clause.

Religious oaths to hold public office were common

In the eight-year period following independence in 1776, 11 of the 13 original states adopted new constitutions. Many of the states ended their religious establishments, but most continued to require religious oaths for civil officeholders.

Only Connecticut and Rhode Island failed to adopt new constitutions, but the constitutions of each of these two states required officeholders to be Protestants. Of the states adopting new constitutions, most simply reaffirmed the religious tests that had been in force during the colonial era. The states that allowed only Protestants to hold office were Georgia (1777), Massachusetts (1780), New Hampshire (1784), New Jersey (1776), North Carolina (1776), South Carolina (1778), and Vermont (1777).

Three states — Delaware, Maryland, and Pennsylvania (all 1776) — required only that officeholders be Christian.

Of the new state constitutions adopted prior to the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, only the Virginia and New York constitutions declined to require religious oaths for civil servants. In New York — in the absence of a constitutional provision addressing the matter of test oaths — state legislation continued to require a test oath that prevented Roman Catholics from holding office until the turn of the century.

The Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, written by Thomas Jefferson and enacted in 1786, proscribed religious test oaths.

U.S. Constitution prohibited religious oaths for federal officeholders

Neither the Articles of Confederation nor the Constitution of 1787 required religious test oaths of federal officeholders.

The Articles were silent on the matter; in seeking to secure religious liberty, however, the Constitution prohibited religious tests for federal officials in Article 4, clause 3. In crafting these documents, the early national leaders did not displace existing religious tests in the states, just as they did not displace religious establishments. Few would have tolerated interference with the states’ exclusive jurisdiction over religion.

Nevertheless, the federal Constitution’s clause prohibiting religious tests became a model that many of the states chose to adopt.

Supreme Court said religious oaths violated First Amendment in 1961 case

By 1800, the states of Georgia, South Carolina, Delaware, Vermont, and Tennessee either had prohibited or removed their constitutions’ religious tests. Moreover, as a newly admitted state, Kentucky, in its 1792 constitution, opted not to require a religious test for civil officeholders. Other states retained their religious tests, however, well into the 19th and even the 20th centuries.

The Supreme Court did not rule on religious tests until 1961, when in Torcaso v. Watkins it ruled that Maryland’s constitutional requirement that every state official declare a “belief in the existence of God” was a violation of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment. The case ruled out the possibility that government at any level can impose constitutionally valid religious tests for public office.

This article was originally published in 2009. Derek H. Davis is the former director of the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies and editor of Journal of Church and State. He is also the former director of the University of Mary-Hardin Baylor Center for Religious Liberty. He now practices law in Dallas, Texas. He is the author or editor of nineteen books and has also published more than 150 articles in various journals and periodicals. He serves numerous organizations given to the protection of religious freedom in American and international contexts.