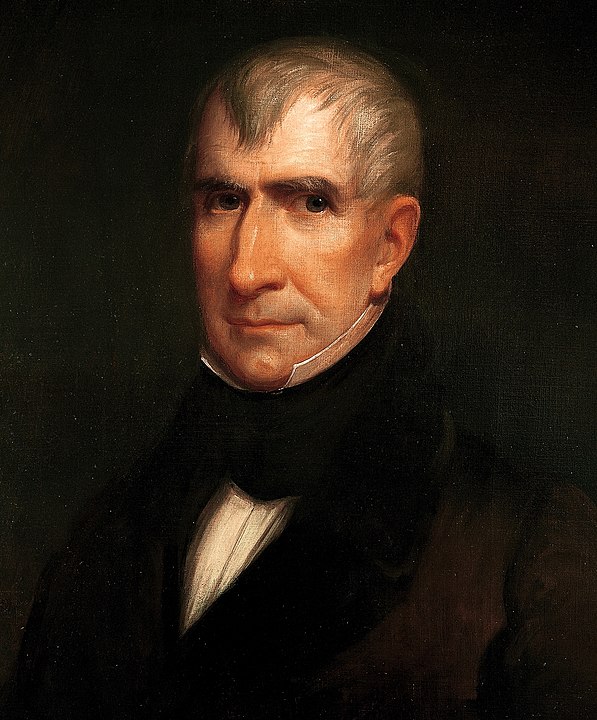

William Henry Harrison (1773-1841) was the first representative of the Whig Party to be elected as president and served the shortest time of any U.S. president after dying of natural causes 31 days after his inauguration.

Born to an aristocratic family in Virginia (his father, Benjamin Harrison, had signed the Declaration of Independence), Harrison had attended Hampton-Sydney College and briefly studied medicine at the University of Pennsylvania before embarking on a military and political career.

After establishing a reputation in battles against Native American Indians and in the War of 1812, he served as Secretary of the Northwest Territory, as the territory’s delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, and as its governor, before then serving as a member of the House of Representatives from Ohio, as a member of the Ohio Senate, as a U.S. Senator, and a Minister to Gran Columbia.

Harrison served only 31 days as president

He was an unsuccessful candidate for president against Martin Van Buren in 1836. But he later elected president and served from March 4 to April 4 of 1841. He was succeeded in office by John Tyler of Virginia.

In the presidential election of 1840, the Whigs had portrayed Harrison as a man of the people who had been born in a log cabin and loved hard cider. Running under the label of “Tippecanoe [the place where Harrison had won a battle] and Tyler Too,” they developed mechanisms, such a torch-light parades that increased voter turnout and essentially beat the Democrats at their own game.

Harrison is best known for having delivered the longest Inaugural Address in history and for his short tenure in office.

Harrison: Citizens are ultimate judge of constitutional meaning

Harrison’s speech is best known for articulating the Whig philosophy that Congress was the central organ of government and that the people were the ultimate judges of constitutional meaning.

Harrison observed that the U.S. Constitution contained both “declarations of power granted and of power withheld” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 72). He observed that “there are certain rights possessed by each individual American citizens, which in his compact with the others he has never surrendered” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 73). Contrasting American government with that of ancient Rome, Harrison expostulated at length on the rights that Americans enjoyed as a result of the First Amendment and other constitutional guarantees:

Far different is the power of our sovereignty. It can interfere with no one’s faith, prescribe forms of worship for no one’s observance, inflict no punishment, but after well-ascertained guilt, the result of investigation under rules prescribed by the Constitution itself. Thee precious privileges, and those scarcely less important of giving expression to his thoughts and opinions, either by writing or speaking, unrestricted but by the liability for injury to others, that that of a full participation in all the advantages which flow from the Government, the acknowledged property of all, the American citizen derives from no charter granted by his fellow-man. (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 73).

Harrison, who feared the effect of power on rulers, thought that the Constitution was defective in allowing presidents to serve for more than a single term and vowed that he would not do so. He further pledged that he would never remove a Secretary of the Treasury without legislative consent, and he recommended that members of the District of Columbia should not be treated as “the subjects of the people of the states” but as “free American citizens” (Inaugural Speeches `1969, 81).

Harrison lauded the presidential veto power as “a conservative power, to be used only first, to protect the Constitution from violation; secondly, the people from the effects of hasty legislation where their will has been probably disregarded or not well understood, and, thirdly, to prevent the effects of combinations violative of the rights of minorities” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 77).

Harrison valued press freedom as a bulwark of civil liberty

Harrison abhorred governmental control of the press. He observed that:

“The maxim which our ancestors derived from the mother country that ‘the freedom of the press is the great bulwark of civil and religious liberty’ is one of the most precious legacies which they have left us. We have learned, too, from our own as well as the experience of other countries, that golden shackles, by whomsoever or by whatever pretense imposed, are as fatal to it as the iron bond of despotism. The presses in the necessary employment of the Government should never be used ‘to clear the guilty or to varnish crime.’ A decent and manly examination of the acts of the Government should be not only tolerated, but encouraged” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 79).

Like a number of presidents who would follow, Harrison thought that talk of abolitionism “is productive of no other consequences than bitterness, alienation, discord, and injury to the very cause which is intended to be advanced” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 830).

Harrison’s penultimate paragraph combined civil religion and religious liberty. Harrison expressed “a profound reverence for the Christian religion and a thorough conviction that sound morals, religious liberty, and a just sense of religious responsibility are essentially connected with all true and lasting happiness; and to that good Being who has blessed us by the gifts of civil and religious freedom” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 87).

Harrison did not nominate any federal judges during his shortened presidency.

His successor, John Tyler, made history by insisting that he was president through the end of the term and not simply an “acting president” until another election could be called. Tyler, who had previously been a Democrat, did not adhere to the Whig philosophy and was not renominated. He was succeeded by Democrat James K. Polk. Harrison’s grandson, Benjamin Harrison, a Republican, later served as president from 1889-1893.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Jan. 16, 2024.