The Sedition Act of 1918 curtailed the free speech rights of U.S. citizens during time of war.

Passed on May 16, 1918, as an amendment to Title I of the Espionage Act of 1917, the act provided for further and expanded limitations on speech. Ultimately, its passage came to be viewed as an instance of government overstepping the bounds of First Amendment freedoms.

Sedition Act passed during World War I

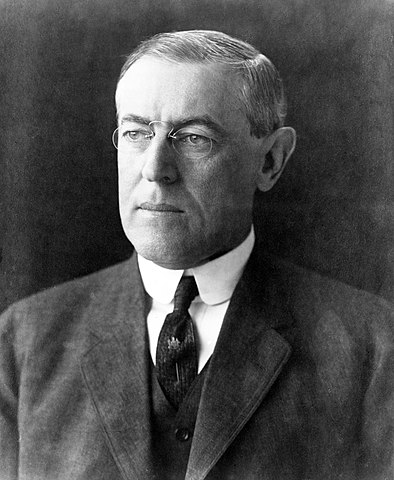

President Woodrow Wilson, in conjunction with congressional leaders and the influential newspapers of the era, urged passage of the Sedition Act in the midst of U.S. involvement in World War I. Wilson was concerned about the country’s diminishing morale and looking for a way to clamp down on growing and widespread disapproval of the war and the military draft that had been instituted to fight it.

Targets were typically individuals who opposed the war effort

The provisions of the act prohibited certain types of speech as they related to the war or the military.

Under the act, it was illegal to:

- incite disloyalty within the military;

- use in speech or written form any language that was disloyal to the government, the Constitution, the military, or the flag;

- advocate strikes on labor production; promote principles that were in violation of the act; or

- support countries at war with the United States.

The targets of prosecution under the Sedition Act were typically individuals who opposed the war effort, including pacifists, anarchists, and socialists. Violations of the Sedition Act could lead to as much as 20 years in prison and a fine of $10,000. More than 2,000 cases were filed by the government under the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918. Of these, more than 1,000 ended in convictions.

Sedition Act convictions upheld against First Amendment challenges

The Supreme Court upheld the convictions of many of the individuals prosecuted under the Sedition Act.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. established the “clear and present danger” test in Schenck v. United States (1919). In upholding Socialist Charles Schenck’s conviction, Justice Holmes wrote that “the most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic.”

The court also unanimously upheld convictions in Debs v. United States (1919) and Frohwerk v. United States (1919).

In Abrams v. United States (1919), the Court reviewed the conviction under the act of Jacob Abrams, who, along with four other Russian defendants, was prosecuted for printing and distributing leaflets calling for workers to strike in an effort to end military involvement in the Soviet Union. The court in late 1919 upheld the conviction.

However, in this instance Holmes, along with Justice Louis D. Brandeis, dissented from the majority, arguing that the “clear and present danger” test was not met under the circumstances arising in the case. Specifically, Holmes felt that Abrams had not possessed the necessary intent to harm the U.S. war effort. In contrast to his majority opinion in Schenck, Holmes’s dissenting opinion in Abrams urged that political speech be protected under the First Amendment.

The Sedition Act of 1918 was repealed in 1920 although many parts of the original Espionage Act remain in force.

This article was originally published in 2009. Christina L. Boyd is an Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Georgia. Her current research focuses on the quantitative examination of judges and litigants in federal courts.