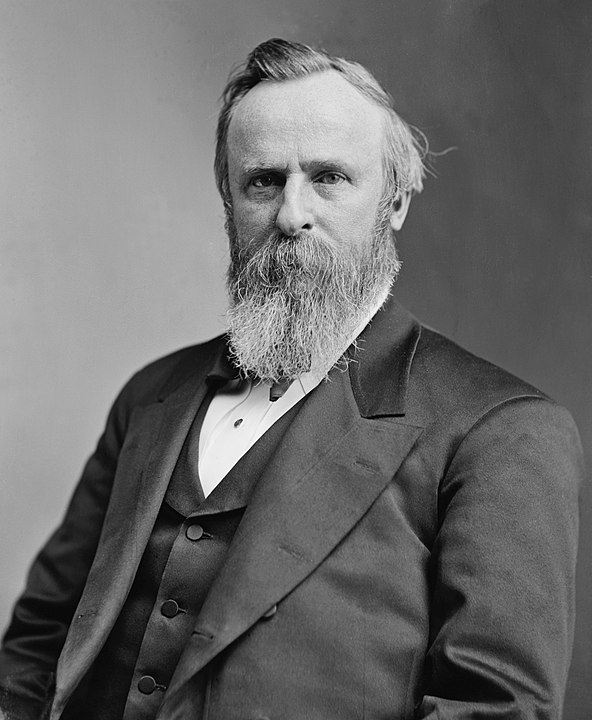

Rutherford B. Hayes of Ohio, a former Whig who became a Republican, served a single term in the presidential office from 1877 to 1881. He followed Ulysses S. Grant and was succeeded by James A. Garfield.

A graduate of Harvard Law School, Hayes had risen to the rank of brigadier general in the Union army and had served in the U.S. House of Representatives and as an Ohio governor before being elected as president.

Hayes wins contested election of 1876

Although Hayes lost the popular vote in the presidential election of 1876 to Samuel A. Tilton of New York, a special congressional commission awarded him all of the 20 contested votes in the electoral college to give him the victory. Hayes, who had supported African American rights, including the adoption of the 15th Amendment enfranchising African American males, promised Democrats to withdraw federal troops from the South, although he continued to fight for African American rights, including the right to vote. In his inaugural address, Hayes, who had promised not to run for reelection, observed that “He serves his party best who serves his country best.”

Hayes vetoed bills to narrow African American rights

Hayes enhanced the powers of the presidency in part by advocating civil service reform. He employed federal troops to break the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, and he used his veto power to void a number of bills seeking to narrow protections for African American rights that Congress adopted during his tenure. Hayes also sought to educate Native Americans.

During Hayes’ term, the Supreme Court decided in Ex parte Jackson (1878) that a congressional law barring information regarding lotteries to be sent through the U.S. mail did not violate the free speech and press clauses of the First Amendment.

In Reynolds v. United States (1879), the high court further ruled that a federal law against polygamy did not violate the free exercise of the First Amendment.

Although Hayes advocated federal aid to education for whites, Blacks, and Native Americans, he supported strict separation of church and state and opposed the establishment of Catholic schools. His wife Lucy, a pious Methodist often dubbed “Lemonade Lucy,” was a strong supporter of the temperance movement.

Hayes appointed John Marshall Harlan I to Supreme Court

As president, Hayes appointed John Marshall Harlan I to the Supreme Court. Harlan became known for penning some of the most notable dissents on the court, including his dissent in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the decision that had approved racial segregation. Harlan was an early advocate of applying the guarantees in the Bill of Rights to the states as well as to the national government.

A state in Paraguay is named after Hayes because he helped negotiate a border dispute between Argentina and that nation that was favorable to the latter (Bombay, 2023).

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Jan. 19, 2024.