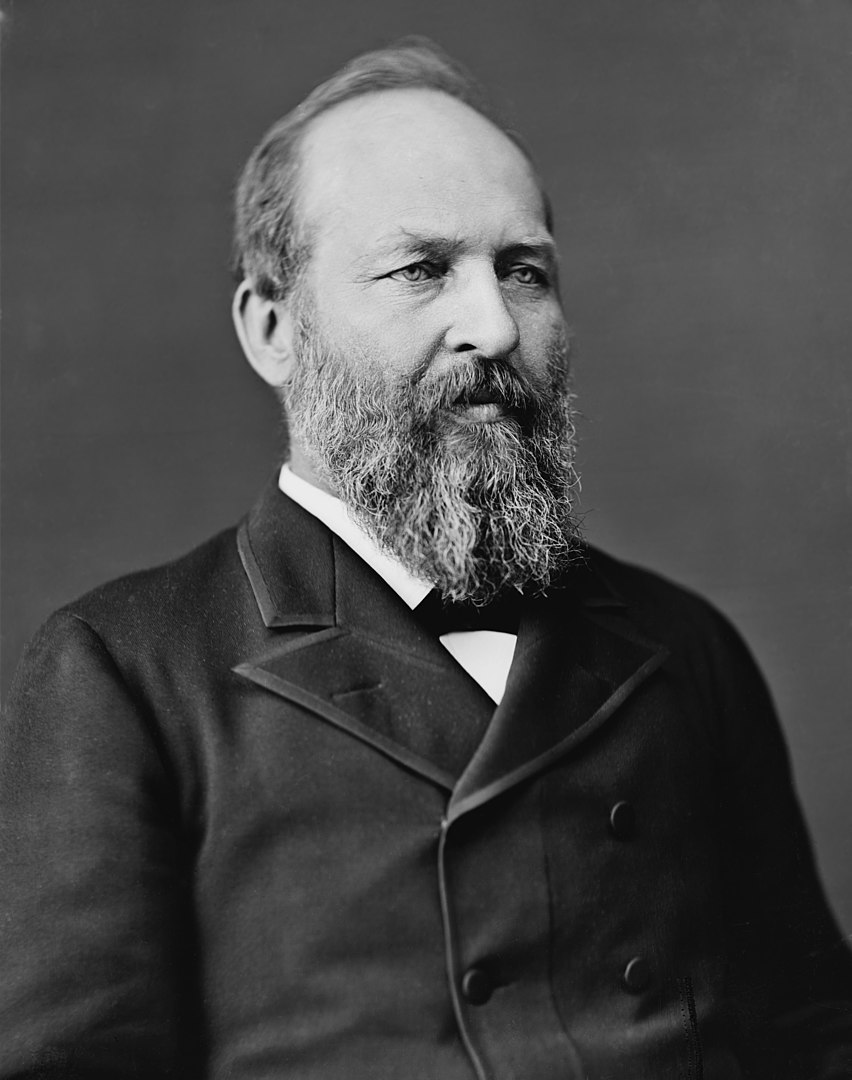

James A. Garfield (1831-1881) was from Ohio and was the last president to have been born in a log cabin. After some time doing manual labor, he studied at what later became known as Hiram College, which was run by the Disciples of Christ, and became a preacher. He subsequently graduated with honors from Williams College, read law and was admitted to the bar.

Garfield argued before the Supreme Court in the case of Ex parte Milligan (1866) where he was able to save civilian Confederate sympathizers who had been sentenced to death by a military court during the Civil War. Garfield had successfully argued that such military courts had no jurisdiction over civilians in areas where such civilian courts were still operating.

After serving in the Ohio Senate, Garfield distinguished himself in the Union Army, rising from the rank of lieutenant to major general. He later served with distinction in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was elected the nation's 20th president in 1880 in a contest with Major General Winfield Scott Hancock. The Republican Party was split between those like Garfield (the Half-Breeds), who favored civil service reforms, and those dubbed the Stalwarts who wanted to continue with the spoils system. Garfield was in the former camp and chose Chester A. Arthur, who was a member of the latter, in part to balance his ticket.

Garfield argued for equal protection for former slaves

Because Garfield died 100 days into his presidency, his interactions with and influences on the First Amendment were not as extensive as that of most other presidents. Moreover, he was president at a time when the Supreme Court had ruled that the provisions of the First Amendment did not yet apply to the states.

In his inaugural address, Garfield argued that American institutions provided “no middle ground for the negro race between slavery and equal citizenship. There can be no permanent disfranchised peasantry in the United States.” Freedmen should accordingly “enjoy the full and equal protection of the Constitution and the laws” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 143). Responding to objections that many African Americans were too illiterate and ignorant to vote, Garfield advocated “the savory influence of universal education” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 144). He further advocated a sound currency backed by gold and silver.

Garfield supported religious freedom, but laws against polygamy

In his inaugural address, Garfield observed: “The Constitution guarantees absolute religious freedom. Congress is prohibited from making any law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.”

Like others of his day, Garfield thought that polygamy was an evil similar to that of slavery, and he believed that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was stymieing the enforcement of polygamy laws. “The Mormon Church not only offends the moral sense of manhood by sanctioning polygamy, but prevents the administration of justice through ordinary instrumentalities of law,” he said, adding that “it is the duty of Congress, while respecting to the uttermost the conscientious convictions and religious scruples of every citizen, to prohibit within its jurisdiction all criminal practices, especially of that class which destroy the family relations and endanger social order.” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 146).

Garfield gained public approval and affirmed presidential appointment power when he appointed William H. Robertson as collector for the Port of New York without the support of the state’s two senators, both of whom resigned in protest (Sutton 2016, 269-270).

Garfield’s Supreme Court appointee upholds law denying polygamists the vote

As president, Garfield appointed to the Supreme Court Stanley Matthews, who served until 1889. In Murphy v. Ramsey (1885), Matthews upheld a federal law denying the right to vote to polygamists.

When Garfield died from an assassin’s bullet and poor medical care 100 days into his administration, his vice president Arthur took up the standard of civil service reform and the Pendleton Act was adopted in 1882.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 17, 2023.