Although the Supreme Court dismissed Ruthenberg v. Michigan, 273 U.S. 782 (1927), on the death of Charles Ruthenberg, the national executive secretary of the Communist Party of the United States, its deliberation in this case proved influential in Whitney v. California (1927).

Justice Louis D. Brandeis used the dissent that he had been preparing in Ruthenberg to form the backbone of his famed concurrence there. Brandeis’s concurrence in Whitney is considered foundational First Amendment law.

Ruthenberg was charged with attending Communist Party meeting

Ruthenberg, a long-time communist agitator, spent most of his life in Ohio, where he had run on several occasions for political office. The Supreme Court had previously sustained his conviction in Ruthenberg v. United States (1918) for interfering with military conscription.

Michigan subsequently charged Ruthenberg with having attended a secret meeting of the Communist Party, which the state alleged had been “formed to teach and advocate the doctrines of criminal syndicalism.”

Brandeis through state had criminalized mere assembly

As the majority of the Supreme Court prepared to uphold the conviction, Brandeis authored a vigorous dissent, refining the “clear and present danger” test that his colleague Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. had introduced in Schenck v. United States (1919).

Although Brandeis expressed clear distaste for communism, he believed the Michigan law attempted to criminalize a “mere act of assembling.”

Brandeis argued that “[i]n a democracy public discussion is a political duty.” Brandeis said that “no danger flowing from speech can be deemed clear and present, unless the incidence of evil apprehended is so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion. Only an emergency can justify repression.”

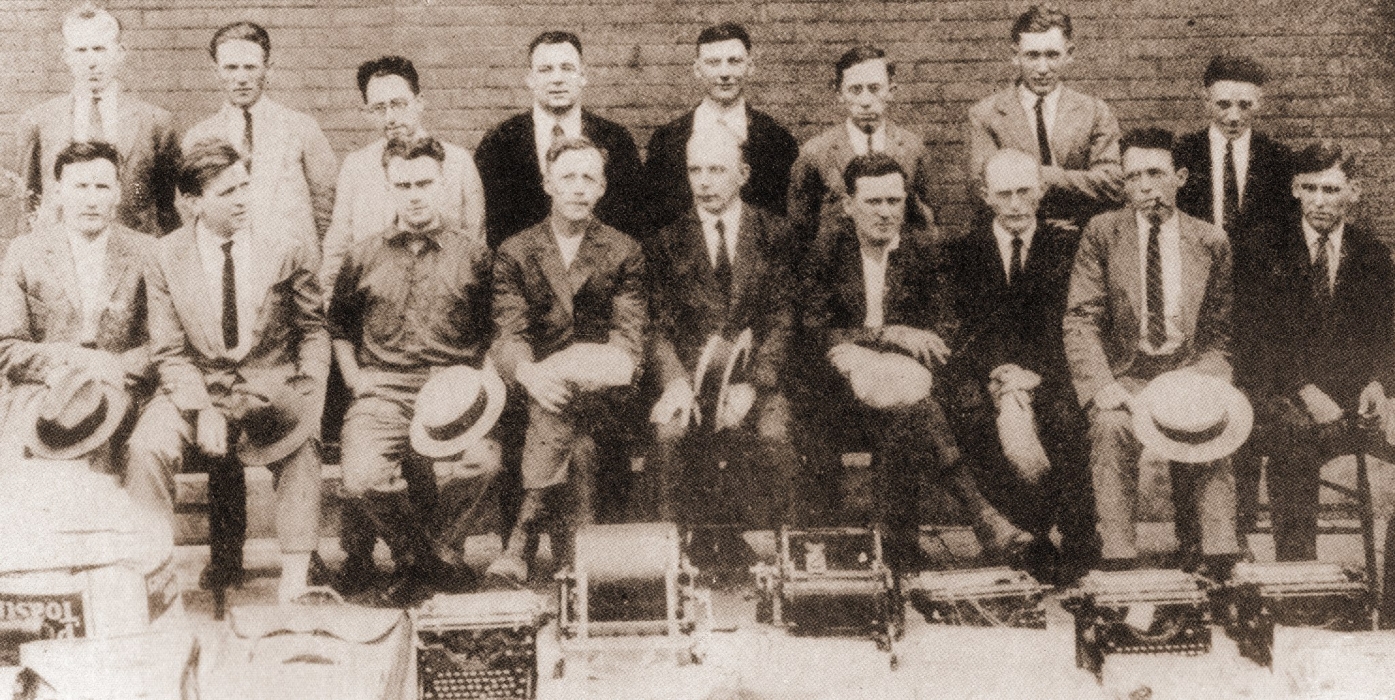

Charles Ruthenberg, seated fifth from left, was among those arrested in the August 22, 1922 raid of the Communist Party convention at Bridgman, Michigan. His conviction under Michigan’s criminal syndicalization law was appealed to the Supreme Court, but was dismissed upon his death. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Brandeis refined First Amendment doctrine to protect speech

Criticizing the “bad tendency” standard for suppressing speech that the Court had announced in Gitlow v. New York (1925), Brandeis said, “Mere bad tendency of the utterance cannot [justify repression].” He noted that “if the only evil apprehended was illegal violence in the final struggle, there could be no basis for a claim that mere assemblage with this society, although formed to advocate the noxious doctrine, would create imminent danger of the evil. There was absent that proximate relation of cause or consequence of which alone the law commonly takes account.” Brandeis observed that Ruthenberg’s advocacy had fallen “short of incitement.”

Ruthenberg died before case was heard; Brandeis used dissent in Whitney concurrence

After Ruthenberg’s death, Brandeis transposed much of this decision to his concurrence in Whitney, for which he had originally authored a short two-paragraph opinion (not surprisingly, scholars have long noted that his concurrence reads more like a dissent). Consistent with the gender of the individual involved in the latter case, in Whitney he added the memorable line that “Men feared witches and burnt women” (Collins and Skover 2005, p. 374).

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) later overturned criminal syndicalism laws, like those that the Court majority had been prepared to uphold prior to the plaintiff’s death in Ruthenberg and that it did uphold in Whitney.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.