The American Romantic and Transcendental movements of the 19th century were a reaction against the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment’s emphasis on science and rationalism as ways of discovering truth.

The writers associated with these movements advocated the right of individuals to dissent and to engage in civil disobedience. They also believed that government may not interfere with freedom of expression.

Their writings influenced the civil rights, equal rights, and anti-war protest movements of the 1960s and 1970s. They also influenced the thinking of some Supreme Court justices and, indirectly, judicial interpretation of the First Amendment.

Among the Romantics were literary giants Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Transcendentalists valued individualism and self-reliance

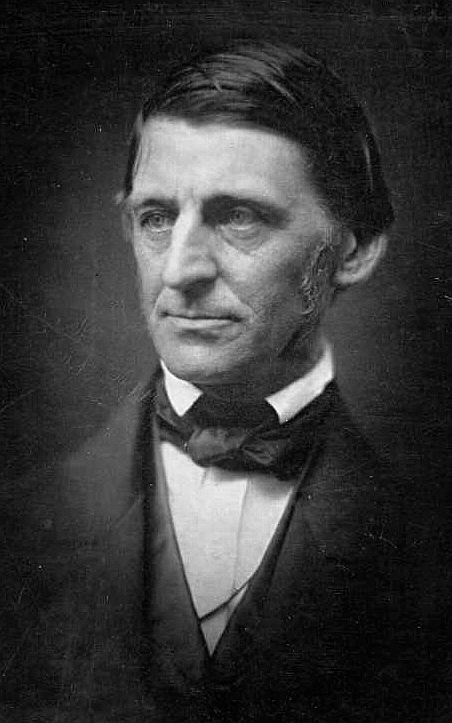

Transcendentalism, which lasted from about 1830 to 1860, was a vital part of the Romantic movement. Ralph Waldo Emerson was its putative leader. Henry David Thoreau and Margaret Fuller were among the principals of the movement.

The Transcendentalists believed there is a divine spirit in nature and in every living soul. Through individualism and self-reliance human beings could reunite with God. A significant part of Transcendentalists’ intellectual foundation was Immanuel Kant’s concept that all knowledge is concerned with ways of knowing objects, not with objects themselves — that is, all knowledge is transcendental.

Emerson’s influential essay Nature (1836) explains Transcendentalism’s main tenets. In Walden (1854), Thoreau explains how to live the good life and be at one with nature. His celebrated essay Civil Disobedience (1849) lauds the benefits of peaceful resistance.

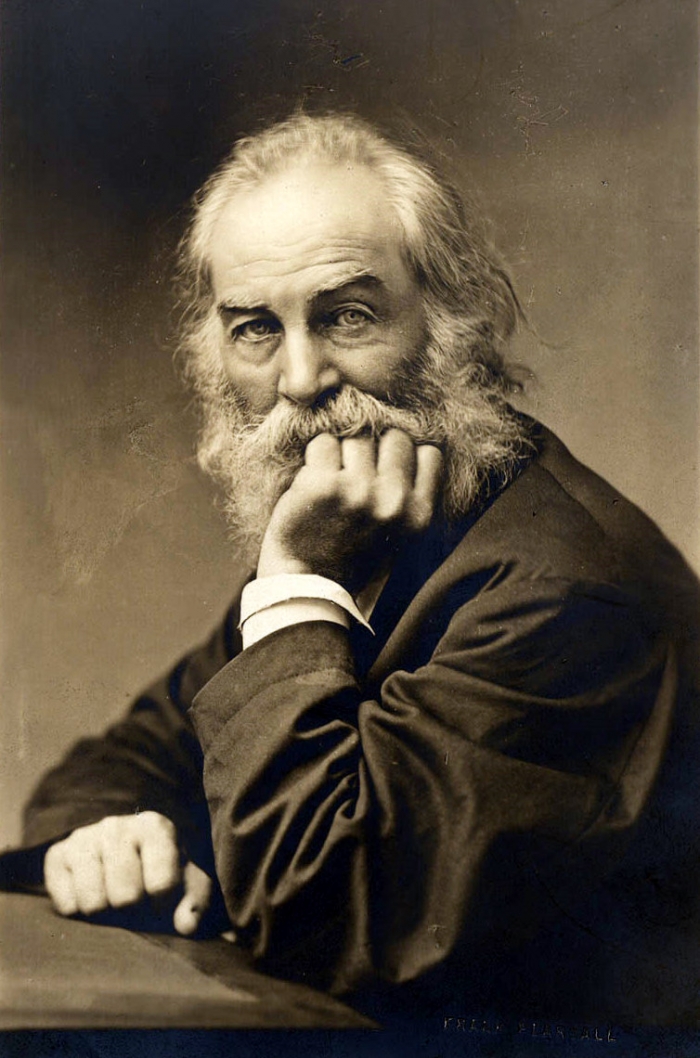

Walt Whitman, who wrote toward the end of the movement, advocated accepting human’s animal nature and reuniting with God through the natural world. His Leaves of Grass (1855) and other poems celebrate freedom, independence, and the value of nonconformity.

Reasoning behind some First Amendment law has roots in Transcendental movement

As a child, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. knew Emerson and repeatedly acknowledged his esteem for the writer.

Although a direct Emersonian influence on Holmes’s thinking remains elusive, some scholars suggest that Holmes’s dissent in Abrams v. United States (1919) not only reflects Emerson’s philosophy of self-reliance but also began a transformation of Holmes’s views on freedom of expression.

And his dissent in United States v. Schwimmer (1929) has a distinctly Emersonian flavor: “If there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other it is the principle of free thought — not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate.”

Justice Louis D. Brandeis, Holmes’s close friend and intellectual partner in developing modern First Amendment law, also admired Emerson. Brandeis’s ideas are thought to have roots in Emerson’s concepts of self-reliance, nonconformity, and individuality. In turn, these two justices influenced the direction of First Amendment jurisprudence.

The opinions of other justices also evoke the Transcendentalist concepts of individuality and nonconformity.

For example, Justice Robert H. Jackson’s stirring words in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), in which he declared that “[i]f there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation” it is that government cannot control what people think or believe, echo Emerson’s and Whitman’s views of the relationships among individuals, religion, and government.

Justice William J. Brennan Jr. revealed a streak of romantic individualism, as well as a belief in personal liberty, in his defense of boycotts, demonstrations, and other forms of civil disobedience as valid means of expression. Examples are his opinions in NAACP v. Button (1963), Edwards v. Aguillard (1987), and Texas v. Johnson (1989).

Walt Whitman, who wrote toward the end of the movement, advocated accepting man’s animal nature and reuniting with God through the natural world. Justice Robert H. Jackson’s stirring words in West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), in which he declared that “[i]f there is any fixed star in our constitutional constellation” it is that government cannot control what people think or believe, echo Whitman’s views of the relationships among individuals, religion, and government. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, circa 1869, public domain)

The Court has referred to writers in First Amendment opinions

There are references to both American Romantic and Transcendental writers in some First Amendment opinions.

- Chief Justice Warren E. Burger referred to Thoreau’s isolation at Walden Pond in his opinion for the Court in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972).

- Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist quoted from Emerson’s “Concord Hymn” and from “Barbara Frietchie,” a poem by Romantic poet John Greenleaf Whittier, in his dissent in Texas v. Johnson (1989).

- Justice Sandra Day O’Connor alluded to Thoreau’s Civil Disobedience in Simon and Schuster v. Members of the New York State Crime Victims Board (1991).

- And in United States v. National Treasury Employees Union (1995), which struck down the section of the Ethics in Government Act of 1978 precluding members of Congress and government employees from accepting honoraria for speaking or writing on issues unrelated to their jobs, Justice John Paul Stevens cited Melville, Hawthorne, and Whitman as examples of government employees who wrote on issues unrelated to their government jobs.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. Judith Ann Haydel (1945-2007) was a political science professor at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and McNeese State University.