John Paul Stevens (1920 – 2019 ) is a former U.S. Supreme Court Justice who was one of the longest-tenured jurists in Court history, serving from 1975 until his retirement in 2010. In his 35 years on the Court, Justice Stevens contributed mightily to First Amendment jurisprudence and seemingly became more speech-protective in his later years on the Court.

Born in Chicago, John Stevens earned his undergraduate degree from the University of Chicago. He then served in World War II as an intelligence officer in the U.S. Navy. He earned a Bronze Star during his military service.

After returning home, he went to law school, earning his degree from Northwestern University Law School. Upon graduation, he clerked for U.S. Supreme Court Justice Wiley Rutledge, a noted defender of church-state separation. Professor Laura Krugman Ray writes that from his clerkship experience, Justice Stevens maintained a deep interest in the Establishment Clause. (Ray, 263).

After his clerkship, Stevens worked mainly in private practice in Chicago, establishing a reputation as an excellent antitrust lawyer. In 1970, President Richard Nixon appointed Stevens to the Seventh U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. In 1975, President Gerald Ford nominated Stevens to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Senate confirmed him unanimously 98-0.

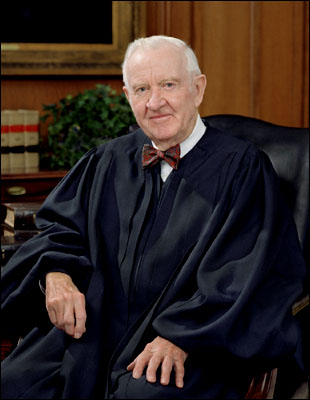

Justice John Paul Stevens in 1975. Stevens was a consistent defender of church-state separation in freedom of religion cases. He wrote the Court’s decision in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), invalidating an Alabama moment of silence law. Stevens reasoned that the Alabama legislature had a clear religious purpose of bring prayer back into the public schools. (AP Photo/DE, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Stevens defended church-state separation

Stevens was a consistent defender of church-state separation in freedom of religion cases. He wrote the Court’s decision in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), invalidating an Alabama moment of silence law. Stevens reasoned that the Alabama legislature had a clear religious purpose of bring prayer back into the public schools. Stevens also authored the Court’s decision in Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000), invalidating a Texas high school district’s practice of announcing prayers over the loudspeakers at football games.

Stevens defended commercial speech

Stevens was a consistent defender of commercial speech in his years on the Court. He authored the Court’s decision in 44 Liquormart v. Rhode Island (1996), invalidating two Rhode Island statutes that prohibited the display of liquor prices. He also authored the Court’s decision in Greater New Orleans Broadcasting Assn v. United States (1999), invalidating a federal law regulating gambling ads. It was during this period that the Court increased the free-speech protections for commercial speech.

Stevens became more speech-protective

Stevens appeared to become more speech-protective when it came to indecent or low-value speech in his later years on the Court. For example, in his early years Stevens authored the Court’s decision in Young v. American Mini-Theatres, Inc. (1976), upholding a Detroit ordinance that regulated the location of adult businesses. Stevens introduced into the Court’s jurisprudence the concept of secondary effects. In a footnote, he explained that the purpose of the law was not to silence or mute offensive expression, but to combat the harmful, secondary effects of adult businesses, such as increased crime and decreased property values.

However, many years later, Stevens dissented in the Court’s secondary-effects cases, such as City of Erie v. PAP’S A.M. (2000). In that decision, Stevens warned that the Court had expanded the secondary effects doctrine beyond its original purpose of upholding land-use regulations of adult-businesses to regulating the content of adult expression, in this case totally nude dancing.

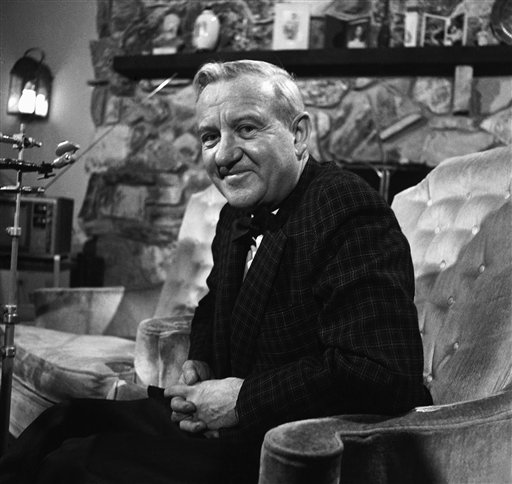

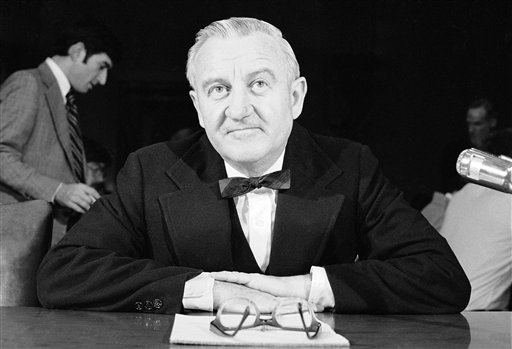

John Paul Stevens waits to testify before the Senate Judiciary Committee for his confirmation hearing in 1975. Stevens appeared to become more speech-protective when it came to indecent or low-value speech in cases like City of Erie v. PAP’S A.M. (2000) in his later years on the Court. Stevens also seemingly became more speech-protective in indecency cases such as Reno v. Aclu (1997). (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Stevens also seemingly became more speech-protective in indecency cases. In his early years on the Court, Stevens wrote the Court’s plurality opinion in FCC v. Pacifica Foundation (1978), upholding the power of the federal agency to fine radio stations for broadcasting indecent speech during daytime hours. However, nearly 20 years later, Stevens wrote the Court’s opinion in Reno v. ACLU (1997), invalidating two provisions of the Communications Decency Act that criminalized the online transmission of indecent or patently offensive expression.

Stevens expressed support for the idea that society should tolerate even offensive speech. In a 1991 address at the University of Chicago Law School, he talked about the “principle of tolerance embodied in the First Amendment.” (Stevens, 29). He delivered a lecture at Yale Law School in October 1992 on the importance of the First Amendment and protection for freedom of speech. He concluded in memorable language: “Let us hope that whenever we decide to tolerate intolerant speech, the speaker as well as the audience will understand that we do so to express our deep commitment to the value of tolerance — a value protected by every clause in the single sentence called the First Amendment.” (Stevens, 1313).

Stevens died on July 16, 2019 at the age of 99.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Daniel Baracskay teaches in the public administration program at Valdosta State University.