Expressive conduct is behavior designed to convey a message; its function as speech means that it has increasingly been protected by the First Amendment. Two rough synonyms are symbolic speech, statements made through the use of symbols rather than words, and speech plus, behavior used by itself or in connection with language to communicate a message.

Expressive conduct allows individuals to express their opinions and contributes to societal debate, but it sometimes produces results that Congress seeks to prevent. When faced with legislation that infringes on expressive conduct, the Supreme Court generally asks whether the regulation is aimed at the expressive or the nonexpressive aspects of the conduct. When the regulation aims at the expressive aspects, the Court assesses it using strict scrutiny. When the regulation aims at the nonexpressive aspects, the Court assesses it using intermediate scrutiny.

Key symbolic speech cases

- The Supreme Court began to address the use of symbols as speech in Stromberg v. California (1931), in which it struck down as a violation of the free-speech clause of the First Amendment a California law that prohibited the display of a red flag as a sign of opposition to government. In writing the opinion for the Court, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. asserted that red flags were a part of free political discussion, and were thus entitled to First Amendment protection.

- In West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), the Court held that compulsory flag salute laws were unconstitutional because they amounted to compelled symbolic speech.

- In Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), the Court held that black armbands worn by students to protest the Vietnam War were symbolic speech, and that this conduct was entitled to First Amendment protection.

- In Texas v. Johnson (1989), the court recognized as speech the burning of an American flag and held that the state could not prohibit this action, either for its message or for its alleged, but unsubstantiated, tendency to cause breaches of the peace.

Two-part test developed

In determining whether expressive conduct deserves First Amendment protection, courts often apply a two-part test taken from the Supreme Court’s decisions in Spence v. Washington (1974) and Texas v. Johnson. First, the speaker must intend to convey a particular message. Second, the message must be one likely to be understood by listeners.

Some expressive conduct involves actions alone, with no use of recognizable symbols. During the Civil Rights movement, protesters used tactics such as sit-ins and freedom rides to show — not just tell — the unfairness of segregation.

In Garner v. Louisiana (1961), sit-in participants were arrested for disturbing the peace. Chief Justice Earl Warren argued for the majority that there was not enough evidence to convict the protesters. Justice John Marshall Harlan II, in concurrence, pointed out that the sit-in behavior was speech, and as such could not be curtailed by a general breach-of-peace prohibition.

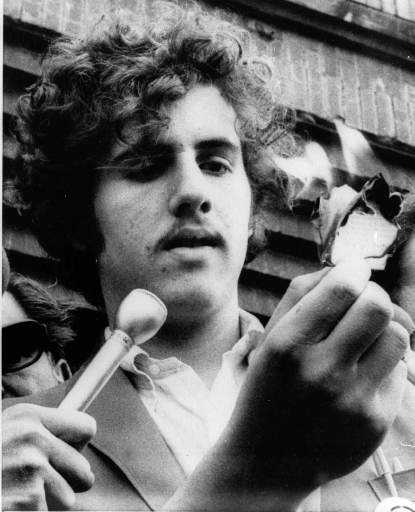

In United States v. O’Brien (1968), the Court, addressing a law prohibiting the burning of a draft card, disaggregated this conduct into its expressive and nonexpressive elements. The Court recognized that burning a draft card was expressive but pointed out that there were valid reasons, unrelated to expression, why the state had an interest in preventing it.

As a result of this opinion, some restrictions on the time, manner, and place of the conduct are permitted as long as they have a minimal impact on the expressive part of the conduct.

This article was originally published in 2009. Katrina Hoch was a doctoral student at the University of California San Diego.