In 1969 President Richard M. Nixon appointed Warren Earl Burger (1907–1995) as the 15th chief justice of the United States, a position Burger held for 17 years.

Burger was born in St. Paul, Minnesota, on September 17, 1907, the fourth of seven children of railroad cargo inspector and traveling salesman Charles Burger and his wife Katherine. Suffering from polio at the age of eight, Burger spent a year at home, reading autobiographies of judges and attorneys; he knew at a very young age that he wanted to be a lawyer.

When Burger reached college age, he turned down an insufficient scholarship from Princeton University and instead enrolled in extension classes at the University of Minnesota in 1925. Two years later, he started to attend night classes at the St. Paul College of Law (now the William Mitchell College of Law), from which he graduated magna cum laude in 1931. He was admitted to the Minnesota Bar the same year.

Burger began his legal career in 1931 as an associate at a law firm where he became a partner in 1935. While practicing law, Burger also taught contract law at his alma mater from 1931 to 1953. A lifelong Republican, Burger played an active part in politics. During the 1952 Republican National Convention, he supported the eventual party nominee, Dwight D. Eisenhower, which led to his appointment in 1953 to head what is today the Civil Division of the Justice Department. President Eisenhower later nominated Burger to the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals in 1955.

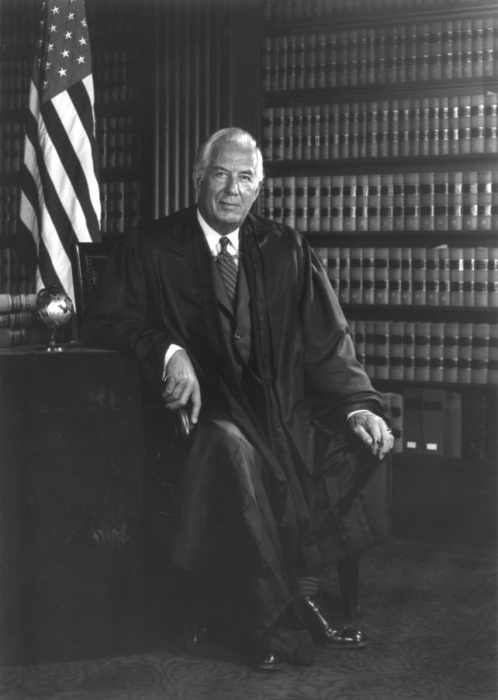

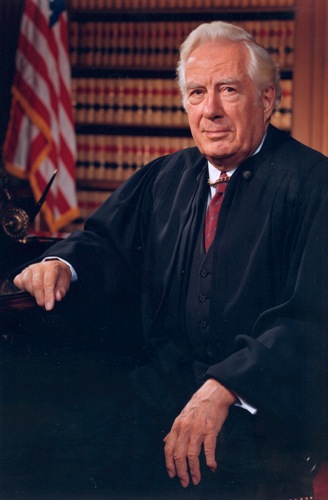

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger in his office at the Supreme Court in 1969. On religious liberty, for example, the Burger Court kept and extended many of the liberal Warren Court’s precedents outlawing state-sponsored religious exercises in public schools. Writing for the Court in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), Burger established a three-prong test for determining whether laws or government actions effectively established religion in violation of the First Amendment. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Burger was a surprise choice for chief justice

Although Burger’s record during his 13 years on the appeals court was largely conservative, especially with respect to criminal cases, he was considered a surprise choice for the Supreme Court when Nixon nominated him to replace retiring Chief Justice Earl Warren.

Burger, who critics said lacked analytical rigor and great eloquence, brought a common sense approach to his decisions, and he was a strong advocate for the Court. He worked to balance liberal and conservative extremes on the Court, to the disappointment of hard-line conservatives who had hoped he would take the Court in a more conservative direction.

Burger Court established the Lemon Test

On religious liberty, for example, the Burger Court kept and extended many of the liberal Warren Court’s precedents outlawing state-sponsored religious exercises in public schools. Writing for the Court in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1971), Burger established a three-prong test for determining whether laws or government actions effectively established religion in violation of the First Amendment. The Lemon test permitted laws supporting religion only if they had a secular purpose, had a primary effect that neither advanced nor harmed religion, and did not create an excessive entanglement between church and state.

In one application of the Lemon test, the Burger Court voted 5 to 4 in Stone v. Graham (1980) to invalidate a Kentucky law that required the posting of the Ten Commandments on classroom walls on the grounds that it violated the first prong of the test and thereby the First Amendment.

The Burger Court, however, sometimes took a more expansive view of the First Amendment religion clauses. For example, in Widmar v. Vincent (1981) the Court concluded that a state university, which had feared violating the establishment clause, could not exclude religious student groups from meeting in facilities available to secular student organizations. Separately in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972), Burger wrote the majority decision that rejected compulsory high school education for the Amish, deeming it a violation of their freedom of religion.

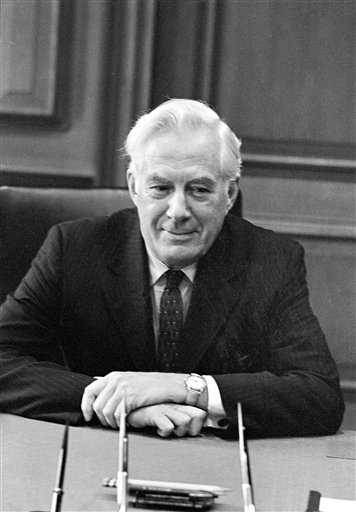

In First Amendment free expression and association cases, the Chief Justice Warren Burger’s Court clarified the Court’s position on prior restraints on the press, maintaining that the government must demonstrate a “heavy burden” of justification to impose such restraints. (Image via Wikimedia Commons)

The Burger Court clarified the Court’s position on prior restraint

In First Amendment free expression and association cases, the Burger Court clarified the Court’s position on prior restraints on the press, maintaining that the government must demonstrate a “heavy burden” of justification to impose such restraints. Burger himself was protective of the freedom of the press; for example, he argued in Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974) that newspapers should not be required to give space to people who were criticized in their pages and wished to reply. He also struck down a gag order restricting coverage of a criminal case in Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart (1976). However, Burger dissented in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), when the majority prohibited prior restraint in the publication of the Pentagon Papers.

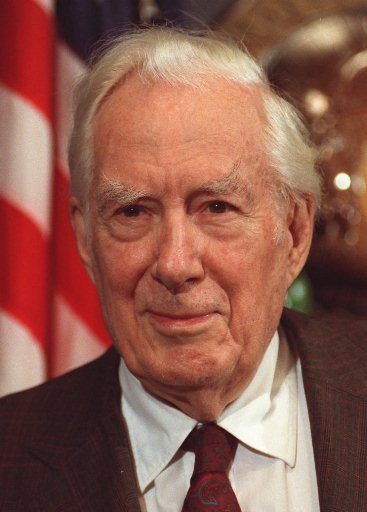

Retired Chief Justice of the United States Warren Burger in 1991. Burger was chief justice from 1969 to 1986, the longest tenure this century. Burger dissented in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), when the majority prohibited prior restraintin the publication of the Pentagon Papers. (AP Photo/Barry Thumma, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Burger was willing to regulate certain categories of speech in schools

In addressing other issues that often arose under the First Amendment, Burger showed willingness to regulate pornography, dirty words, and disruptive speech in schools. He wrote the Court’s decision articulating standards under which government could prosecute obscenity in Miller v. California (1973) and its companion case, Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton. In Bethel School District No. 403 v. Fraser (1986), his last opinion for the Court, Burger wrote that public school officials could punish students for lewd and vulgar speech.

Burger retired in order to chair the Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution. He was delighted that the Constitution’s 200th birthday, September 17, 1987, was also his 80th birthday. After his wife, Elvera Stromberg Burger, passed away in 1994, Burger’s health rapidly deteriorated; he died of congestive heart failure on June 25, 1995. He was laid in state in the Great Hall of the Supreme Court and buried next to his wife at Arlington National Cemetery.

Salmon A. Shomade, J.D., Ph.D., is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Oxford College of Emory University and an Adjunct Professor of Law at Emory University Law School. Dr. Shomade is the author of Decision-making and Controversies in State Supreme Courts (2018). This article was published in 2009 when Professor Shomade was at University of New Orleans.