Felix Frankfurter (1882–1965) championed civil rights during 23 years as a justice on the Supreme Court, but he frequently voted to limit civil liberties, believing that government had a duty to protect itself and the public from assault and that the Court should exercise judicial restraint to promote democratic processes.

Frankfurter was an immigrant who taught at Harvard Law School

Born in Vienna, Austria, Frankfurter arrived in New York City with his family in 1894, knowing no English. They lived in a Jewish ghetto on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, where his father became a door-to-door salesman. Adapting quickly to his adopted nation and its language, Frankfurter entered City College of New York in 1897 as part of a program that allowed him to finish high school and to earn a college degree. He graduated magna cum laude in 1902 and briefly attended New York Law School. He then transferred to Harvard University, became editor of the Harvard Law Review, and graduated at the top of his class in 1906.

After a stint in private practice, Frankfurter became an assistant U.S. attorney in New York under Theodore Roosevelt appointee Henry L. Stimson. In 1911 Stimson was appointed secretary of war by President William Howard Taft; Frankfurter became counsel to the Bureau of Insular Affairs. In 1914 Frankfurter accepted a position teaching at Harvard Law School.

Throughout his tenure at Harvard, Frankfurter was known nationally as the consummate teacher and scholar, an outspoken advocate of liberal causes, as well as a skilled participant in public affairs. President Woodrow Wilson appointed him as a judge advocate to investigate labor unrest, and then as counsel to the Mediation Commission. He also served as a Zionist delegate to the Versailles Peace Conference, and he urged Wilson to incorporate the Balfour Declaration into the treaty.

Frankfurter helped start the ACLU

In 1920 Frankfurter helped to organize the American Civil Liberties Union. Two years later, in 1922, he, along with Roscoe Pound, published Criminal Justice in Cleveland, a study of crime reporting in Cleveland newspapers. The study concluded that the recent crime wave in Cleveland was a fiction created by the press that resulted in inflated punishments and gross miscarriages of justice.

His vigorous criticism of the conviction and 1927 execution of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, the anarchists accused of bank robbery and murder in Braintree, Mass., resulted in another book, The Case of Sacco and Vanzetti (1927). In all, Frankfurter authored or edited 12 books and many scholarly articles for law journals, and he frequently contributed articles to the New Republic, which he helped to found.

Justice Felix Frankfurter had an illustrious career before his time on the Supreme Court. He was an Austrian immigrant who went on to teach at Harvard and help organize the American Civil Liberties Union. In this photo, Frankfurter and wife Marion are shown leaving their home in 1939 for the Supreme Court. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Frankfurter was an influential champion of outcasts

In his speeches and writings, Frankfurter remained a steady and passionate champion of the poor, the downtrodden, the persecuted, and the wrongly convicted. He was sometimes maligned as a “Red,” and on one occasion Harvard alumni demanded that he be fired.

Frankfurter also conveyed an unshakeable love for his adopted country and its laws and institutions. He had a fine sense of the American democratic process that emphasized the supremacy of the legislature, and he held to a belief that appointed judges should not inject their personal viewpoints into law. He increasingly advocated that the will of the people be exercised through their elected legislatures and not by an appointed judiciary.

Frankfurter influenced both his students and the government. He was a nationally recognized expert on labor law, constitutional law, and civil procedure. Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis D. Brandeis relied on Frankfurter to appoint their law clerks, who usually were his top students. Many of them went on to serve important posts in the New Deal. He also regularly communicated with Justice Harlan Fiske Stone after President Calvin Coolidge appointed Stone to the Court in 1925.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt’s election to the presidency in 1932, Frankfurter frequently visited the White House, where he became a valued adviser to New Deal programs. He enthusiastically supported the social and economic engineering of the programs Congress adopted, some of which he helped to formulate. When Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo died in 1938, FDR nominated Felix Frankfurter to replace him. The Senate confirmed his appointment on January 16, 1939, and he was sworn in on January 30.

As justice, Frankfurter favored judicial restraint, precedent

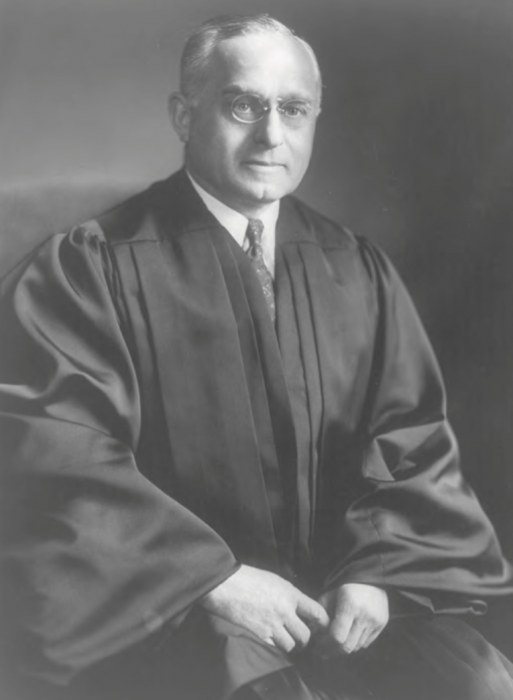

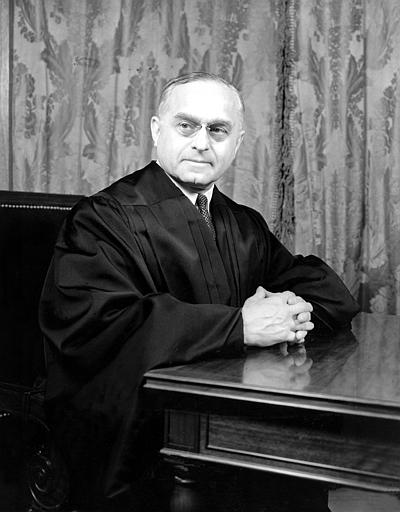

Justice Felix Frankfurter in 1939. As a justice, Frankfurter relied heavily on precedent and judicial restraint. He believed strongly in not inserting his opinion into his judgements “no matter how deeply I may cherish them or how mischievous I may deem their disregard.” (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

On the Court, Frankfurter initially voted to uphold the constitutionality of New Deal programs. He generally supported the civil rights of minorities, personally opposed the death penalty, and often voted to rein in the powers of the police. He became the most fervent proponent of judicial restraint, often lecturing in his opinions on the propriety of allowing the elected branches of government great leeway in their interpretations of the Constitution and frequently quoting Holmes and Brandeis in his opinions as a tribute to their judicial self-restraint. He also tended to sustain precedents as a matter of principle.

In a notable majority opinion in Minersville School District v. Gobitis (1940), Frankfurter upheld the constitutionality of a Pennsylvania law requiring schoolchildren to salute the American flag. In this case, the two Gobitis children,

Frankfurter stressed that national unity promoted national security, that the Court should avoid interfering with the legislative prerogative in passing such laws, and that the free-exercise clause did not excuse people from complying with general laws of the state that do not aim to restrict religious beliefs — the “secular regulation” rule. After the Court’s ruling, violent incidents broke out across the nation targeting Jehovah’s Witnesses and their property.

Frankfurter believed he could not inject his personal opinions into the Constitution

In Jones v. City of Opelika (1942), also a Witnesses case, Justices Hugo L. Black, William O. Douglas, and Francis W. Murphy stated in a dissent that Gobitis should be overturned. That change of sentiment led directly to West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), a similar flag-salute case, in which the Court reversed Gobitis.

Justice Robert H. Jackson’s classic 6-3 majority decision stressed that the government could not compel patriotism through a forced flag salute. Frankfurter felt compelled to justify his earlier opinion by writing a vigorous dissent that is now a classic in its own right. As a member of “the most vilified and persecuted minority in history,” he believed he was not “insensitive to the freedoms guaranteed by the Constitution,” but that “as a member of this court” he believed that he had no justification for injecting his personal opinions into the Constitution “no matter how deeply I may cherish them or how mischievous I may deem their disregard.”

Frankfurter preferred to examine perceived violations of the due process clause of the 14th Amendment on a case-by-case, or fundamental fairness, basis. By contrast, Justice Hugo Black and others advanced the idea of total incorporation — that is, applying all the provisions of the Bill of Rights, including those of the First Amendment, to the states by means of the due-process clause of the 14th Amendment. Frankfurter generally preferred to evade exercises of judicial review and to protect civil liberties through statutory construction rather than through constitutional interpretation.

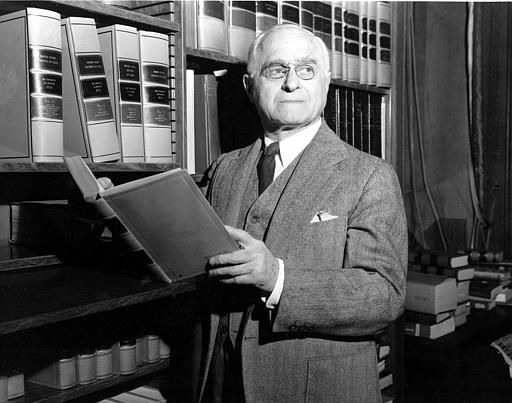

Justice Felix Frankfurter in his office in 1957. Frankfurter was not known as a champion of First Amendment rights. He upheld a group libel law and upheld statutes that some characterized as prior restraint. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Frankfurter was not a great defender of the First Amendment

Frankfurter was not one of the great defenders of the First Amendment during his long tenure on the Court. For example, he wrote the Court’s majority opinion in Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952), which upheld an Illinois group libel law. Similarly, he wrote the Court’s majority opinion in Kingsley Books, Inc. v. Brown (1957), which upheld a New York law allowing city officials to seize material alleged to be obscene before a judicial hearing. The dissenters — which included free-speech stalwarts William Douglas, Hugo Black and William J. Brennan Jr. — deplored the statute as a classic prior restraint.

Although he was regarded as a liberal, Frankfurter is not easily categorized. Intensely loyal to his adopted country, he firmly believed that the elected representatives of the people should be as free as possible of judicial intervention.

He was a brilliant scholar and an opinionated advocate of ideas, often appealing to his supporters and yet irritating to his adversaries. His public disagreements with Justices Black, Douglas, and Frederick M. Vinson at times caused tension on the Court. In an obscure admiralty case, Justices Owen J. Roberts and Frankfurter severely criticized Justice Harlan Fiske Stone for his tendency to overturn precedent, which to Frankfurter appeared “gloatingly to show up the unwisdom, if not the injustice, of our predecessors.”

He believed that such a tendency would ultimately bring the Court and the law into disrepute. Eventually, Black and Frankfurter reconciled their differences. Douglas, however, never resolved his conflict with Frankfurter. Frankfurter resigned from the bench in 1962 after a severe stroke and died three years later.

This article was originally published in 2009. James R. Belpedio was a Professor of History at Becker College.