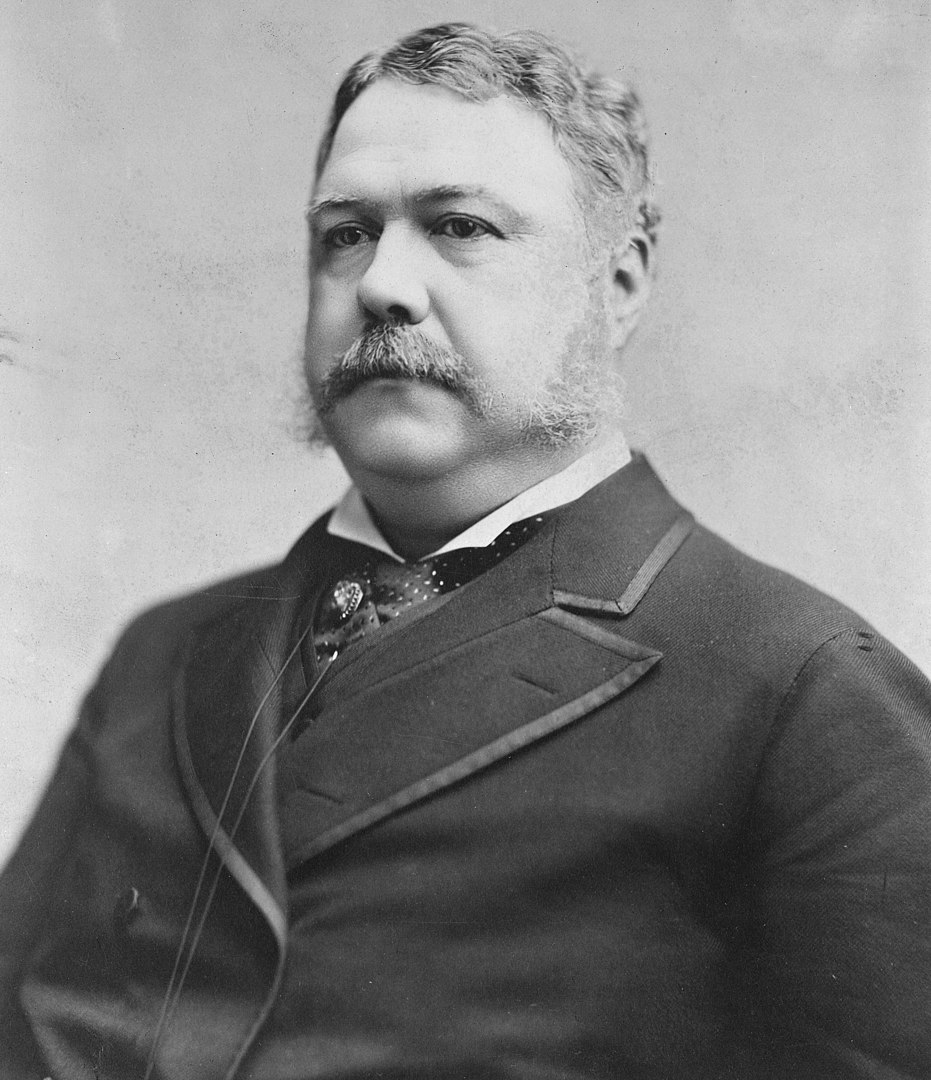

Chester A. Arthur (1829-1886) was born in Vermont (his father was a Baptist minister) but was raised in New York where he spent most of his life. He graduated from Union College, served for a time as a teacher, read law, and was admitted to the New York bar.

During the Civil War, he served as a brigadier general over the state militia. In 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him as Collector of the Port of New York, a post from which Rutherford B. Hayes suspended him in 1878. He then served as chairman of the New York Republican Party and as vice president under James Garfield, who had selected him to balance the ticket.

Because Garfield was assassinated by a disappointed office seeker after less than a year in office, Arthur served almost a full term from 1881 to 1885. It is believed that Arthur may have been the first person to add the words “so help me God” to his presidential oath (Vile 2023, 119).

Arthur was president when the Supreme Court decided in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883 that the provisions of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, which were designed to prohibit discrimination in places of public accommodation, were unconstitutional because such actions represented private rather than public action. In 1873, the court had previously decided in the Slaughterhouse Cases that the privileges and immunities clause of the 14th Amendment had not intended, as some argued, to apply the provisions of the First Amendment or other provisions of the Bill of Rights to the states.

It was not until the court’s decision in Gitlow v. New York (1925) that the court would begin applying provisions of the First Amendment to state entities, thus limiting judicial review in this area.

Arthur vetoed a law banning Chinese immigration for 20 years, but signed a subsequent law, passed by more than the two-thirds majorities of both houses and thus likely to be adopted over his veto, that shortened this time to 10 years (Sutton 2016, 280). In another setback for civil rights, the Supreme Court held in Elk v. Wilkins (1884) that the 14th Amendment had not made citizens of Native-American Indians other than those who went through the naturalization process.

First Amendment issues during Arthur’s presidency

Although Arthur had been long associated with the spoils system, in 1882, Congress adopted and he signed the Pendleton Act, which helped create the civil service system. That same year, in Ex parte Curtis, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld an earlier law that prohibited U.S. governmental officials from requesting or receiving money from other employees for political purposes, despite a dissent from Justice Joseph Bradley, who thought the law conflicted with the First Amendment.

The Hatch Act of 1939 has imposed further limits on partisan activities by governmental employees.

In 1862, during the Civil War, Congress had adopted what was known as the “Ironclad Test Oath,” requiring civil servants to pledge not only that they supported the U.S. Constitution but that they had always done so. Congress repealed this requirement in 1884.

In another matter, in 1882, Congress also adopted the Edmunds-Tucker Act, seeking to take property from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, which was still advocating polygamy. The Supreme Court upheld this law in Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints v. United States (1890) and church leaders subsequently renounced polygamy.

Arthur appoints Gray, Blatchford to Supreme Court

Arthur appointed two justices to the U.S. Supreme Court. They were Horace Gray who served from 1881 to 1902 and Samuel Blatchford who served from 1882 to 1893.

Arthur suffered from a kidney ailment known as Bright’s Disease and died within a year after he was succeeded in office by Grover Cleveland, the first Democrat to be elected since James Buchanan.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 17, 2023.