Although many U.S. Founding Fathers believed that slavery was at best a necessary evil, and some supported the American Colonization Society, with the intention of allowing freed slaves to return to Africa, over time northern sentiment grew more opposed to slavery.

Meanwhile, southern leaders increasingly defended the institution as a positive good that was beneficial to both Whites and Blacks, the latter of whom they considered to be inferior. In truth, slaves had few, if any, of the rights guaranteed in either the First Amendment or the Bill of Rights, and their families could be split at the will of their masters

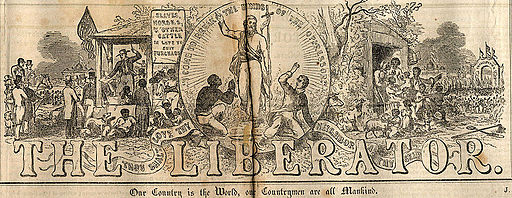

Although it had earlier roots (most Quakers had, for example, opposed slavery), the movement to abolish slavery is usually tied to William Lloyd Garrison’s founding of the abolitionist newspaper the Liberator in 1831. The Liberator called for immediate end of slavery. The movement spread swiftly and ferociously.

The movement prompted defenders of slavery to use legal and some illegal means to stem the tide of anti-slavery sentiment, including limiting the ability to speak against the practice of slavery.

Events in the 1820s created fear of abolition in the South

Several events created an atmosphere of fear in the South so that measures to thwart abolitionism could be passed under the guise of maintaining peace and order.

The 1820 Missouri Compromise was crafted to accommodate the demands of pro-slavery as well as pro-abolition movements, by pairing Missouri’s acceptance into the Union as a slave state with Maine’s entry as a free state and banning slavery in the west north of the line 30°30’. In fact, it satisfied only the moderates on both sides. Extreme pro-slavery elements objected to it because it provided a precedent by which Congress had power to regulate slavery. Abolitionists opposed it because it allowed slavery to continue to spread in some of the areas.

The 1822 revelation of Denmark Vesey’s planned slave rebellion in South Carolina shocked southerners. Vesey had organized to lead an army of slaves through Charleston, killing white people in their path. Only the betrayal of Vesey by some of his army prevented his plan from being put into practice. The realization that blacks in several states actually outnumbered whites made residents of slave states all too aware of their tenuous position of power.

The tariff of 1828, designed to aid Northern manufacturers by increasing the cost of imported goods, also raised fears of economic pain. Having barely recovered from the Panic of 1819, economic interests in the South cast about for a way to fight back. John C. Calhoun provided that means with his impassioned advancement of “nullification” of federal laws. Eventually the tariff was repealed, but the legal justification of independent state action had been broached.

Forceful abolitionist speech was met with speech bans

Abolitionists began to push more forcefully, urging “any means necessary” to defeat slavery. Within a few years, they would organize the Underground Railroad to help slaves escape. In response to mass mailings of the Liberator, North Carolina passed laws to forbid teaching blacks to read or to provide them with reading material. Nat Turner, an enslaved preacher, led an uprising in 1831 in Virginia, which responded by banning nighttime religious services for slaves.

In 1835 and 1836, there was an unsuccessful movement in Congress to ban abolitionist writings from the U.S. mail.

Abolitionist preaching led to heightened tensions in the North as well. In 1834–1835, such tensions resulted in riots in New York City and in Philadelphia. In the wake of these events, Alabama, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia published open letters and sent official communications to northern states urging them to control the disruptive activities of abolitionists.

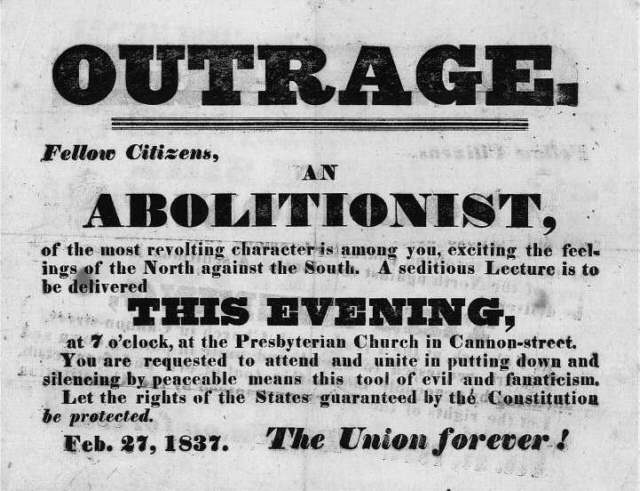

Forceful abolitionists led to tensions in the North and the South. Opposition to abolition led to the limiting of some First Amendment freedoms. (Advertisement urging the peaceable breakup of an abolitionist meeting in New York via Library of Congress, public domain)

Congress passes gag rule to limit anti-slavery speech

In response to the overwhelming submission of petitions to the U.S. House of Representatives in support of abolitionist legislation, pro-slavery and moderate anti-slavery forces banded together to pass a gag rule in the House.

The rule, originally passed in 1836 to produce a “cooling off” period, was renewed and strengthened to ban virtually any mention of abolition or the limiting of slavery or the slave trade.

As with earlier attempts to ease tensions, the irreconcilable goals of the two sides doomed this effort to failure.

Former president John Quincy Adams argued against the rule, offering resolutions to lift it at every chance. The House eventually censured him for his actions.

More than 100 mob attacks recorded against anti-slavery press

Rather than cooling passions, the gag rule merely forced activists to seek other channels of activity.

These included increased mailings of newspapers and lecture tours designed to incite the public against the evils of slavery as well as to encourage slaves to resist their masters. Around this time, anti-abolitionists held meetings and formed societies throughout the Southern states.

More than 100 mob attacks on anti-slavery newspapers took place prior to the Civil War. These included an 1836 mortal attack against Elijah Lovejoy, the editor of the Alton Observer in Illinois who had previously been forced to flee Missouri after his press there had been destroyed (Little 2023).

The implementation of the gag rule also helped fuel the abolitionist movement in northern states, resulting in the election of enough new members of Congress to overturn it in 1844.

Calhoun attempted to introduce a similar gag rule in the Senate. His measure was blocked, however, in favor of a rule to force a vote on whether to consider receiving a petition rather than voting to accept the petition. This provided pro-slavery senators with a guaranteed method of preventing discussion of abolition within the Senate.

Missouri outlaws speech against slavery; other states follow

In 1837, Missouri banned abolitionist expression of any kind. Within a couple of years, every Southern state had adopted laws that limited the freedom of speech with regard to abolitionist sentiment.

Southerners were especially wary of strangers, and local meetings of anti-abolition societies often demanded that state legislatures pass even stricter measures, calling for special taxes on abolitionists, and in some cases their immediate expulsion or imprisonment.

In parts of Louisiana, strangers could be arrested for conversing with blacks. Agitators and abolitionists sometimes had bounties on their heads.

Ex-slaves became some of more effective speakers against slavery

Some of the most effective opponents of slavery were ex-slaves. One of the most important was Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), who worked closely with Garrison and published the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. He delivered a particularly powerful anti-slavery speech at an Independence Day event in 1852.

Henry Highland Garnet (c. 1815-1882), an African-American Presbyterian minister, argued powerfully for abolitionism. Harriet Tubman (1822-1913) was a former slave who helped slaves flee to free states. Sojourner Truth (1797-1883) delivered a powerful talk entitled “Ain’t I a Woman.” Maria W. Steward (1803-1879) is believed to be the first African American woman to give an anti-slavery speech to an audience of both men and women.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, a white woman who was the daughter of pastor Lyman Beecher, further evoked sympathy for slavery and opposition to the institution with her publication of the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1852.

John Brown was another white abolitionist, albeit one who resorted to violent action in Kansas and at Harper’s Ferry Virginia (now West Virginia). His failed attempt in October of 1859 to seize the armory at Harper’s Ferry and spark a slave revolt resulted in his capture and execution. His case became a cause celebre in which his calm demeanor led him to be considered as a martyr.

In response to mass mailings of The Liberator, an anti-slavery publication, North Carolina passed laws forbidding teaching backs to read or to provide them with reading material. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Lincoln, Constitution abolished slavery

In time, Northern sentiment fueled by abolitionism and Southern sentiment fueled by anti-abolitionism and states’ rights led to Civil War as the Southern states seceded following the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, the first Republican president. Lincoln emphasized the statement in the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal,” and believed the Founders had hoped for the institution’s ultimate extinction. His party had been largely founded in opposition to the spread of slavery.

Lincoln initially viewed the Civil War as a means of preserving the Union, but eventually he used it to eliminate slavery as well, through emancipation. On Jan. 1, 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation recognizing the freedom of slaves behind Confederate lines as a war measure.

The U.S. government formalized the abolition of slavery with the 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865. In attempting to guarantee the rights of former slaves, the 14th Amendment, ratified in 1868, declared that all persons born or naturalized within the United States were citizens thereof and entitled to “equal protection of the law” and the “privileges and immunities” of U.S. citizens. It also included a clause providing for “due process of law.” In time, this provision would become the vehicle through which the Supreme Court would apply provisions of the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, to the states after decades of only applying it to the national government.

First Amendment rights of association were later evoked by groups like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) who organized to guarantee equal rights to all citizens.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in February 2024 by John R. Vile, dean of the Honors College and a history professor at Middle Tennessee State University. Thurman Hart is an Adjunct Instructor of Political Science at New Jersey City University.