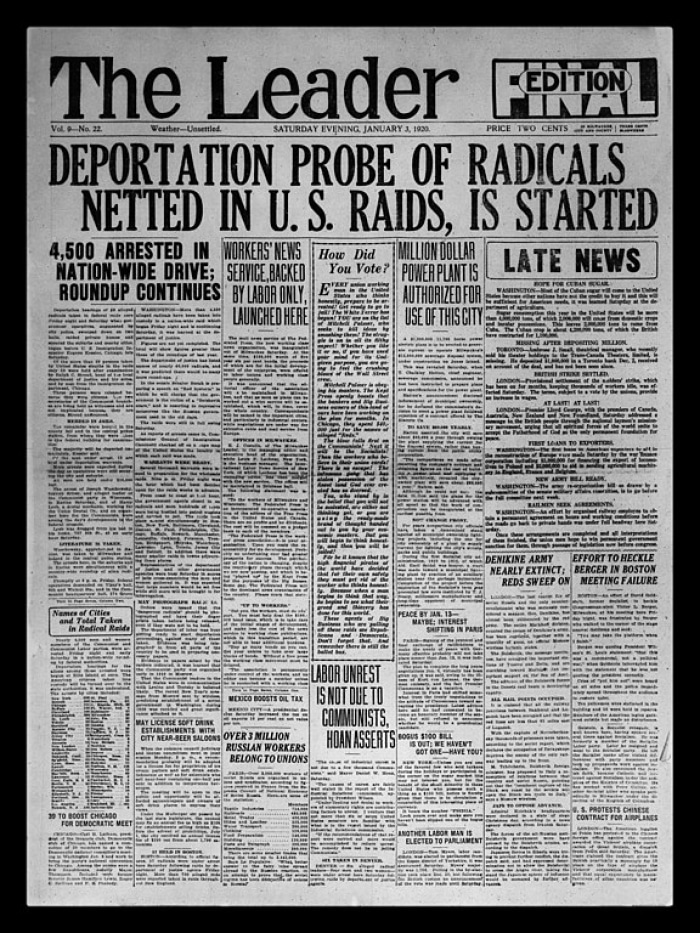

The Supreme Court in United States ex rel. Milwaukee Social Democratic Publishing Co. v. Burleson, 255 U.S. 407 (1921), upheld the third assistant postmaster general’s decision to revoke the second-class mailing privilege that the post office had granted to the publisher of the Milwaukee Leader.

The postmaster had decided that the publication was “non-mailable” material because its content conflicted with the Espionage Act of 1917.

Supreme Court upheld denial of mail permit to socialist newspaper Milwaukee Leader

Justice John H. Clarke’s opinion for the majority emphasized that the postmaster had held a proper hearing (and had thus not denied the publisher due process under the Fifth Amendment), that other Court decisions had upheld the constitutionality of the Espionage Act, and that the denial of the permit did not violate the First Amendment.

In examining the newspaper, the postmaster had found a number of “false reports and false statements, published with intent to interfere with the success of the military operation of our Government, to promote the success of its enemies, and to obstruct its recruiting and enlistment services.”

Clarke observed that the publication was not aimed at modifying or repealing laws but rather encouraging their violation. He wrote, “The Constitution was adopted to preserve our Government, not to serve as a protecting screen for those who while claiming its privileges seek to destroy it.”

Denying that it would be practical to examine every issue of the paper, Clarke decided that “Government is a practical institution adapted to the practical conduct of public affairs.” He noted that the postmaster had not excluded the paper from the mails, but only from the lower rates provided by second-class privileges. If the publisher wanted such rates renewed, it was up to it “to mend its ways,to publish a paper conforming to the law, and then to apply anew for the second-class mailing privilege.”

Brandeis warned of censorship, abridging First Amendment freedom

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Louis D. Brandeis feared that a decision made in time of war could also influence practice in times of peace. He did not believe that Congress had extended to the postmaster the right to deny second class status on the basis of content, nor did he think the postmaster either had the power to exclude the paper from the mail or to deny it a second-class rate.

Although the law spoke of a “permit,” Brandeis argued that “the right to the lawful postal rates is a right independent of the discretion of the Postmaster General. The right and conditions of its existence are defined and rest wholly upon mandatory legislation of Congress.” Brandeis warned that the construction of the law that the majority accepted would abridge freedom of the press by leading to “effective censorship.”

Holmes: Allowing postmaster to stop distribution of papers that might carry treason would confer despotic power

In a separate dissent, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. argued that the only power that the postmaster had in the case of nonmailable materials was “to return them to the senders.”

To give the postmaster power to enjoin distribution of papers that he thought might carry treason or obscenity was to give him potentially despotic power. Holmes observed that “the use of the mails is almost as much a part of free speech as the right to use our tongues, and it would take very strong language to convince me that Congress ever intended to give such a practically despotic power to any one man.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.