Although it is counterintuitive to think that the U.S. might censure a film that positively portrayed the American Revolution, Judge Benjamin Franklin Bledsoe did so on Nov. 30, 1917, when he ordered the confiscation of “The Spirit of ’76” and the jailing of its producer.

'Spirit of '76' confiscated for depiction of British

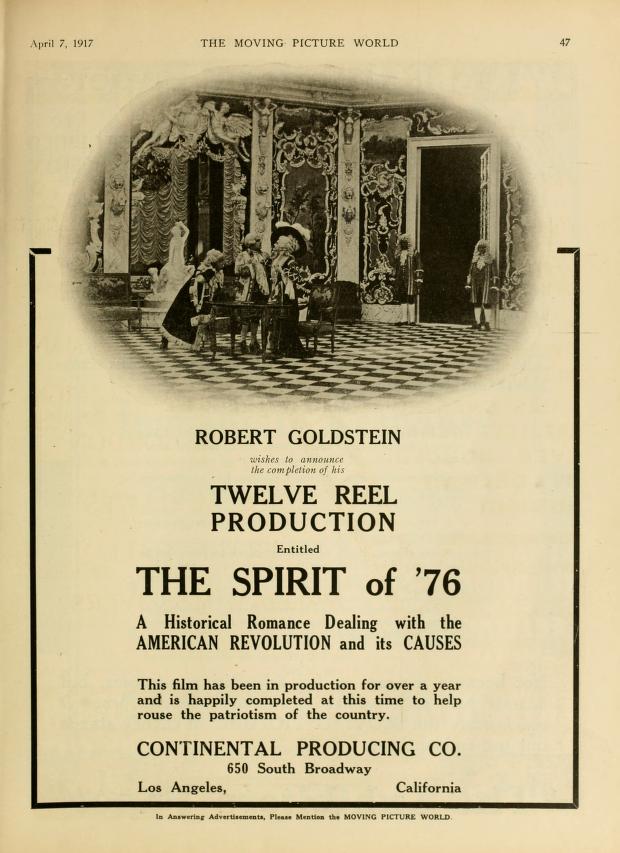

The film was produced by Robert Goldstein, a German-Jewish American who had previously produced a 10-minute film entitled ”1776,” or the “Hessian Renegades.” The new film followed on the heels of D.W. Griffith’s commercial success of “The Birth of a Nation” (1915), which glorified the Ku Klux Klan.

Goldstein’s film included inspiring scenes depicting the signing of the Declaration of Independence and Paul Revere’s Ride, but unfortunately its released was ill-timed, coming out after American entry into World War I as an ally with Great Britain.

Although Goldstein had agreed before police censor boards to omit scenes involving a British soldier sticking a bayonet through a child’s crib, the Wyoming Massacre of Patriots in Pennsylvania, and assaults on American women, he later restored them. For this, he was charged with treason and violating the Espionage Act of 1917 for stirring up hatred of an American ally and thus undermining the war effort.

Judge: Film created 'animosity’ toward WWI ally Great Britain

Although Judge Bledsoe sympathized with stockholders who had invested, some quite heavily, in the film, he thought that the interest in national security was paramount.

Recognizing that “History is history, and fact is fact,” Bledsoe emphasized the current context in which the U.S. was allied with Great Britain. In such context, “whatever may be the excuse ... for the exploitation of those things that may have the tendency or effect of sowing dissension among our people, and of creating animosity or want of confidence between us and our allies,” such a film “weakens our efforts, weakens the chance of our success, impairs our solidarity, and renders less useful the lives we are giving, to the end that this war may soon be over and peace may soon become a thing substantial and permanent with us.”

Believing the scenes of British atrocities during the Revolutionary War were both unnecessary and were likely “to excite or inflame the passions of our people, or some of them,” Bledsoe thought they were inappropriate for the time.

Although the film’s depictions might “at another time or place or under different circumstances ... be harmless and innocuous,” they were not at this time. Referring to the “‘right of free speech,”’ upon which such great stress in now being laid,” Bledsoe wrote “that which in ordinary times might be clearly permissible, or even commendable, in this hour of national emergency, effort, and peril, may be as clearly treasonable, and therefore properly subject to review and repression. The constitutional guaranty of ‘free speech’ carries with it no right to subvert the purposes and destiny of the nation.”

Filmmaker sentenced to prison, film destroyed

Indicating his reservations about confiscating private property, after the jury rendered a guilty verdict, the judge nonetheless ordered the film’s originals to be turned over to the government “until such time as, under changed conditions, it may properly be presented.” He sentenced Goldstein to 10 years in prison and fined him $5,000, although he was freed in 1921. The government apparently destroyed or lost the film in the interim.

This decision was typical of governmental repression of First Amendment freedoms during the Wilson Administration and World War I. Bledsoe’s opinion’s emphasis on context is similar to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ decision in Schenck v. United States (1919) where he employed the clear and present danger test.

Bledsoe’s emphasis on the tendency of a film to excite passion that might undermine the war effort is similar to the Court’s bad tendency test in Gitlow v. New York (1925).

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.