The Taft-Hartley Act, known officially as the Labor-Management Relations Act, was passed by Congress on June 23, 1947, over a veto by President Harry S. Truman, who described the legislation as a “slave-labor bill.”

In regulating labor, the law addressed appropriate forms of symbolic speech, as well as acceptable and unacceptable regulation of the right to association. The law also contained a controversial provision about the participation of communist members as union leaders.

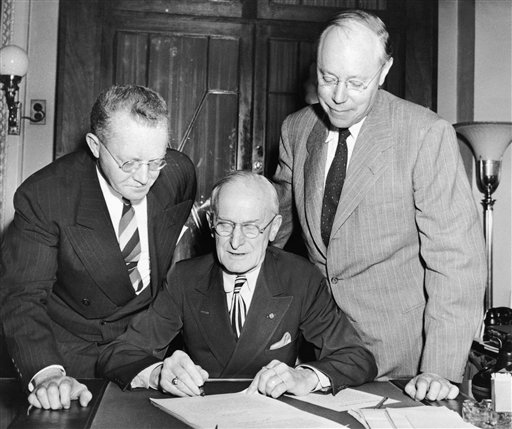

Named for its two sponsors, Sen. Robert A. Taft, R-Ohio, and Rep. Fred A. Hartley Jr., R-N.J., the act amended the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 (the Wagner Act) and, in doing so, severely restricted the activities and powers of labor unions.

The Wagner Act had been the most important labor law providing impetus to labor organizations and giving workers the right to organize, join labor unions, and engage in concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining. Although the provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act codified earlier Supreme Court rulings about employer rights in expressing opposition to unions, it delineated as well their behavior toward their employees’ participation in union activities. The act also established the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to control labor disputes.

Law gave government ability to investigate labor disputes and order injunction against strikes

In addition to its other controls of labor disputes, the Taft-Hartley Act allowed the president to appoint a board of inquiry to investigate labor disputes in instances in which a strike might endanger the public’s health or safety. Upon receipt of the board’s report, the president could ask the attorney general to seek a federal court injunction to prevent or block any strike action from taking place or continuing. If the court found the strike was endangering the public’s health or safety, it could grant the injunction and order the disputing parties to reach a settlement within 60 days.

Even though it maintained various aspects of the Wagner Act of 1935, the 1947 act prohibited some labor union practices.

For example, it outlawed discrimination against nonunion members by union hiring halls and closed shops (a closed shop was a business or establishment that hired only union members).

One contentious provision allowed union shops (which required new recruits to join the labor union within a certain period of time) unless state law forbade them — that is, the states passed “right-to-work” legislation outlawing union shops.

Another provision required all union officers to take an oath and file an affidavit within the preceding twelve-month period stating that they were not members of the Communist Party or affiliated with any party that believed in or advocated the overthrow of the U.S. government.

Law prohibited certain union activity and contributions to political campaigns

Other provisions prohibited:

- the use of pickets, sympathy strikes, or boycotts to compel an employer, other than one’s own, to bargain with an unrecognized union;

- the use of secondary boycotts, in which a union encourages employees to strike against their employers to compel the employers to halt doing business with another employer with whom the real dispute exists; and

- the use of jurisdictional strikes and boycotts in which a union refuses to work in order to assert its members’ rights to particular job assignments and to protest the assignment of disputed work to members of another union or to unorganized workers.

The act also forbade unions to contribute to political campaigns.

Supreme Court has upheld many provisions of Taft-Hartley Act

Many provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act have been upheld.

For example, in American Communications Association v. Douds (1950) the Court upheld the noncommunist affidavit provision.

In International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers v. National Labor Relations Board (1951), the Supreme Court ruled that the section of the act that prohibited secondary boycotts “carries no unconstitutional abridgment of free speech.”

Although the federal courts have upheld most of the 1947 act, with the exception of the provisions about political expenditures, some lawmakers have attempted (unsuccessfully) to repeal it.

The Landrum-Griffin Act of 1959 did amend some features of the Taft-Hartley Act, including the restrictions on secondary boycotting which were further tightened.

This article was originally published in 2009. Dale Mineshima-Lowe is Managing Editor for the Center of International Relations, researcher and Associate Lecturer in both the Department of Politics and Department of Geography at Birkbeck, University of London, and Tutor of Politics and History at the City Lit, adult education college in Central London.