Picketing occurs when a person or a group of people stands, marches, or patrols inside, in front of, or about any premise with the intent to persuade an occupant or patron of the premise regarding some point of view or to protest an action, attitude, or belief. Since Thornhill v. Alabama (1940), courts have held that picketing is a form of expression that triggers First Amendment review.

Government can regulate time, place, and manner of picketing on public property

Picketing on public property is governed by the frequently quoted principle expressed by Supreme Court Justice Owen J. Roberts in Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939): “Streets and parks . . .have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, [for] time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions.”

Nearly a half century earlier, however, the Court in Davis v. Massachusetts (1897) affirmed a decision in which then Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. upheld the conviction of a person who made a public address on the Boston Common without getting a permit from the mayor. Holmes stated that “for the Legislature . . .to forbid public speaking in a highway or public park is no more an infringement of the rights of a member of the public than for the owner of a private house to forbid it in his house.”

While the government may regulate the time, place, and manner of use of public property based on the normal and ordinary use of the property, such regulations must serve a significant government interest and be neutral in content, not favoring any particular point of view over another.

While the government may regulate the time, place, and manner of use of public property based on the normal and ordinary use of the property, such regulations must serve a significant government interest and be neutral in content, not favoring any particular point of view over another. In this photo, embers of the American League for Peace and Democracy wore gas masks in Philadelphia while picketing the German Consulate, Sept. 16, 1938. The pickets protested Germany’s aims in Czechoslovakia. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court has changed opinions on picketing on private property

In Marsh v. Alabama (1946), a divided Supreme Court, speaking through Justice Hugo L. Black, held that the public had the same interest in seeing “that the channels of communication remain free” on private property.

In a case involving a store in a shopping center, Amalgamated Food Employees Union Local 590 v. Logan Valley Plaza (1968), the Court followed Marsh. Writing for the Court, Justice Thurgood Marshall stated that “under some circumstances, property that is privately owned may, at least for First Amendment purposes, be treated as though it were publicly held.” Marshall went on to determine that the “shopping center here is clearly the functional equivalent of the business district of [the company town] involved in Marsh.” In a telling statement, Marshall wrote that the “State may not delegate the power, through the use of its trespass laws, wholly to exclude those members of the public wishing to exercise their First Amendment rights on the premises in a manner and for a purpose generally consonant with the use to which the property is actually put.”

Just four years later, the Court, backing away from Logan, held in Lloyd Corporation, Ltd. v. Tanner (1972) that “the First and Fourteenth Amendments safeguard the rights of free speech and assembly by limitations on state action, not on action by the owner of private property used nondiscriminatorily for private purposes only.” In this case, which involved the distribution of anti-war literature at a shopping center, the Court not only determined that the First Amendment was inapplicable to private property, but it also found that the due process clauses in the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, as well as the Fifth Amendment’s prohibition of the taking of private property for public use without just compensation, were available to private property owners.

A divided Court affirmed Lloyd in Hudgens v. National Labor Relations Board (1976). Justice Potter Stewart, writing for the Court, stated that “It is . . .a commonplace that the constitutional guarantee of free speech is a guarantee only against abridgment by government, federal or state.” Stewart expressed the view that Lloyd overturned Logan, but this opinion was shared only by a plurality of the Court; Justice Lewis Powell, the author of the Court’s opinion in Lloyd, and Justice Byron White disagreed. In any case, if Lloyd did not overrule Logan, Hudgens did.

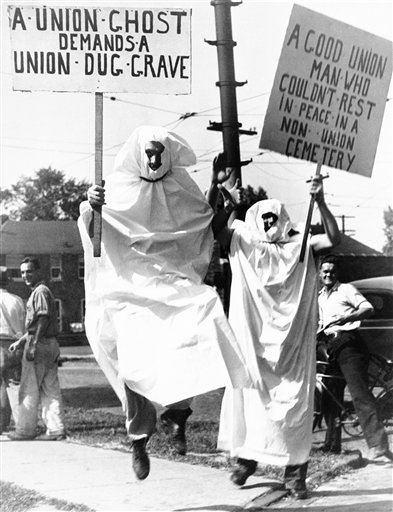

While the Court continued to give lip service to upholding the Thornhill principle that picketing was a First Amendment right, it nonetheless continued to restrict the right. In this photo, these sheet-covered sign-carriers are CIO union cemetery workers picketing the Woodmere Cemetery in Detroit, Aug. 7, 1940. They demanded wage increases, a closed shop and one week vacations. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court has continued to restrict picketing

While the Court continued to give lip service to upholding the Thornhill principle that picketing was a First Amendment right, it nonetheless continued to restrict the right. One of the leading cases in this respect is International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. Vogt, Inc. (1957), which involved a picket that attempted to “coerce” an employer to “coerce” its employees to join a union. State officials deemed the picket a violation of a Wisconsin statute that made it an unfair labor practice for an employee individually or in concert with others to coerce, intimidate, or induce an employer to interfere with any of his employees in the enjoyment of their legal rights. In Vogt, the majority found that “picketing, even though ‘peaceful,’ involved more than just communication of ideas and [thus] could not be immune from all state regulation.” The Court ruled that “valid state policy in a domain open to state regulation” trumps the national First Amendment right to picket.

This article was published in 2009. Clyde E. Willis (1942-2017) worked an attorney for 25 years before starting a second career as a professor. He taught political science for 18 years at Middle Tennessee State University. He wrote the Student’s Guide to Landmark Congressional Laws on the First Amendment.