In Schaefer v. United States, 251 U.S. 466 (1920), the Supreme Court upheld the convictions of three German-American newspaper publishers under the Espionage Act of 1917 based on the character of editorial changes they made to writings that they re-published.

The ruling represented one of a number of setbacks for civil liberties in the World War I era.

Editors, colleagues found guilty of espionage for false reports hindering war with Germany

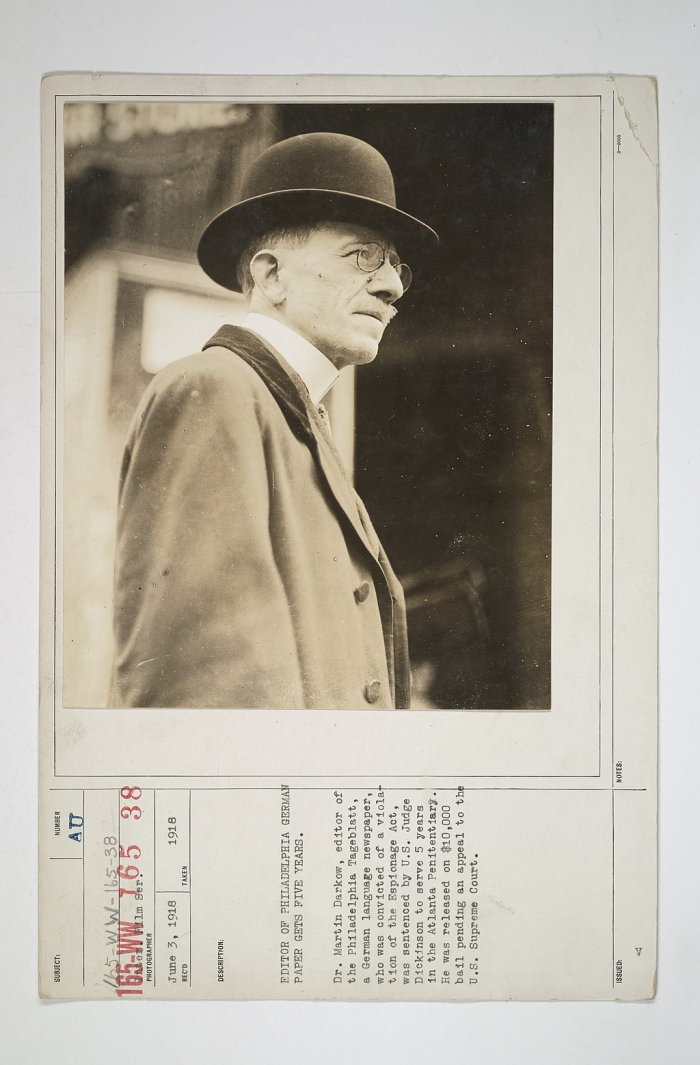

On September 10, 1917, federal officials arrested Peter Schaefer and four colleagues at the Philadelphia Tageblatt, a left-leaning German-language newspaper featuring articles condensed and reprinted from other sources.

The government charged them with willfully mistranslating or abridging the original publications and thus violating the Espionage Act’s provisions forbidding “false reports” to hinder the U.S. war effort. (Two of the editors were also indicted for treason, but the charges were dismissed.)

Supreme Court upheld espionage convictions, used clear and present danger test

Five justices concurred with Justice Joseph McKenna’s opinion in asserting that the clear and present danger test supported three of the convictions.

They agreed with the lower court arguments that the articles “weakened the spirit of recruiting” and that the Espionage Act’s restraints were neither “excessive nor ambiguous.”

Convictions of two of the men, including Schaefer, were overturned because of insufficient evidence linking them to publication of the articles.

Brandeis said prosecutions threatened First Amendment freedom

In dissent, Justice Louis D. Brandeis, joined by Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., vehemently disagreed. Brandeis dismissed the idea that mere editing and re-publication could be grounds for prosecution and insisted that the Tageblatt’s articles had been taken out of context. He warned that such prosecutions would “threaten freedom of thought and of belief.”

In a separate dissent, Justice John H. Clarke urged the exoneration of another one of the defendants, a bookkeeper with no editorial input, who he believed was the victim of a “flagrant mistrial.” Clarke asserted that the First Amendment was not at issue in the case.

Within a few months, President Woodrow Wilson pardoned all three men, in part in response to a petition by 10,000 Philadelphia residents and the regret expressed publicly by their former prosecutor, U.S. attorney Francis Fisher Kane.

This article was originally published in 2009. Christopher Capozzola is Professor of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is the author of Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (2008).