The preferred position doctrine expresses a judicial standard based on a hierarchy of constitutional rights so that some constitutional freedoms are entitled to greater protection than others. In the 20th century, the doctrine represented a preference for individual liberties and civil rights. Thus, the standards the Supreme Court used in determining whether there was an infringement on individual liberties and civil rights, especially those related to the First Amendment, would be more exacting than the reasonableness tests used in evaluating economic issues.

Holmes and Cardozo introduced the hierarchical ordering of constitutional rights

The first explicit mention of a hierarchical ordering of constitutional rights came in the majority opinion written by Justice Benjamin N. Cardozo in Palko v. Connecticut (1937). The original concept, however, may be traced to Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who suggested that the Court should not substitute its judgment for that of the legislature in economic matters and formulated the clear and present danger test in Schenck v. United States (1919), which recognized the primacy of the First Amendment.

It was Justice Cardozo in Palko who argued that Americans had a handful of fundamental rights that were the “very essence of a scheme of ordered liberty.” Among these were the First Amendment freedoms of speech, press, and religion. The Court has periodically added other rights to the list. When dealing with one of these fundamental rights, the Court would subject the state’s restriction to strict scrutiny and ignore the normal presumption of constitutionality.

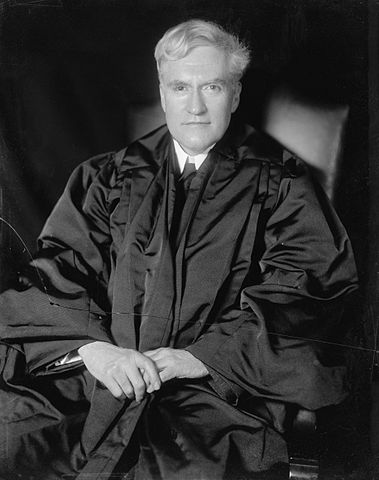

In Footnote 4 of the majority opinion in United States v. Carolene Products (1938), an economic regulation case, Justice Harlan Fiske Stone argued that when the Court evaluated economic issues, it should adopt a relaxed presumption of constitutionality using the rational basis standard, which argues for deference to the legislature, but when legislation affected fundamental rights or singled out “discrete and insular minorities, ”the Court should assume the laws are unconstitutional. Thus, in Stone’s words, civil rights and individual liberties should occupy a “preferred position” in the Court’s consideration.

The preferred position doctrine worked its way from a footnote to majority support, although Justice Felix Frankfurter was generally critical of the attempt of the Court to create a hierarchy of rights. He argued that such an ordering of rights was not part of the Constitution, but rather was a reflection of the personal values of the justices.

Justice Harlan Fiske Stone argued in Footnote 4 of the majority opinion in United States v. Carolene Products (1938), an economic regulation case, that when the Court evaluated economic issues, it should adopt a relaxed presumption of constitutionality using the rational basis standard, which argues for deference to the legislature, but when legislation affected fundamental rights or singled out “discrete and insular minorities, ”the Court should assume the laws are unconstitutional. Thus, in Stone’s words, civil rights and individual liberties should occupy a “preferred position” in the Court’s consideration. (Image via Library of Congress, between 1925 and 1932, public domain)

Preferred position doctrine used in First Amendment cases

The preferred freedoms, or preferred position, doctrine is reflected in the tests and doctrine that the Court has relied on in a number of different First Amendment areas. The creation of a catalog of fundamental rights, the use of strict or moderate scrutiny to deal with questions of discrimination, and the selective application of the Bill of Rights to the states reflect the idea that some rights and liberties are held in a preferred position.

The Warren Court promoted the preferred position doctrine, expanding civil liberties and civil rights. The Burger Court slowed the expansion of rights and liberties in some areas, but generally kept the preferred freedoms doctrine alive. The Rehnquist Court rejected the “double standard” and some of the tests that were constructed under its umbrella. In free exercise jurisprudence, the Court tended to reject the test articulated in Sherbert v. Verner (1963) in favor of the less stringent test used in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990). Critics charged that the Rehnquist Court, in fact, placed economic issues on a higher plane than individual liberties and civil rights. They claim that the Rehnquist Court, in fact, adopted a double standard and a preferred freedom doctrine, but it was a preference for property rights rather than individual liberties. It will take more cases to determine whether (or in what form) the preferred position doctrine will surface during the years of the Roberts Court.

This article was originally written in 2009. Richard L. Pacelle, Jr. is professor and department head in Political Science at the University of Tennessee. Pacelle’s primary research focus is the Supreme Court. His research includes concerns with policy evolution particularly regarding the First Amendment and the role of policy entrepreneurs in the judiciary, Supreme Court agenda building and decision-making, and inter-branch relations.