John G. Roberts Jr. (1955– ), the 17th chief justice of the United States, did not have an extensive track record revealing his personal or judicial views about First Amendment issues when he was sworn in on September 29, 2005. However, he has had an indelible impact on the First Amendment in his years on the Court.

Roberts argued cases before the Court as a lawyer

Born in Buffalo, New York, and raised in Long Beach, Indiana, John Roberts earned both undergraduate and law degrees from Harvard, where he served as managing editor of the law review. During a successful career as an appellate lawyer, Roberts earned a reputation as a leading practitioner before the Court both in the solicitor general’s office of the Justice Department and in private practice at Hogan & Hartson, a Washington, D.C., law firm. During this period, Roberts wrote briefs in or argued a number of First Amendment issues; however, it is difficult to know when he was advancing a client’s views and when the arguments reflected his own ideas. During his tenure as a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, he did not handle many First Amendment cases.

Roberts said Court’s First Amendment standards could be clearer

Roberts was questioned about First Amendment issues during his confirmation hearings before the Senate Judiciary Committee in September 2005. In the course of several days of testimony he expressed concern that the Supreme Court’s tests for speech in a public forum or other setting are “unsettled.” He also said that the Court’s standards for both establishment and free exercise cases “could be clearer.” He gave a glimpse of a philosophical view when he said, “. . . the First Amendment serves a purpose. It’s not just there because the framers thought this was in general a good idea. . . . It provides access to information and allows the people in a free society to make a judgment about what their government is up to.”

Chief Justice John G. Roberts is sworn in by Justice John Paul Stevens in 2005 while President George W. Bush looks on. Roberts’s wife Jane holds the Bible. Roberts’ first major opinion as chief justice in a First Amendment case came in Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights (2006), a case involving a law requiring law schools to provide military recruiters access to the school’s career services offices and interviewing rooms in order to receive funding. Roberts said that the law involved conduct, not speech, and did not violate the freedom of association in the First Amendment. (White House photo by Paul Morse, public domain)

Roberst first major First Amendment opinion was in Rumsfeld

Roberts’ first major opinion as chief justice in a First Amendment case came in Rumsfeld v. Forum for Academic and Institutional Rights (2006). A group of law schools and law professors challenged the constitutionality of a federal law, named for Rep. Gerald B. H. Solomon and known as the Solomon amendment. Under the law, a law school that denied military recruiters access to the school’s career services offices and interviewing rooms would forfeit Defense Department aid for the entire university. The schools argued that the law forced them to endorse the military’s intolerance of gays and lesbians and to support the military’s presence, thus violating free speech and free association rights of schools and professors.

As chief justice, Roberts assigned the decision to himself and produced a unanimous 8-0 opinion. (Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. did not take part in the case.) Roberts rejected the First Amendment claims, shedding light on his view of what constitutes free speech. Roberts viewed the requirements of the Solomon amendment as involving conduct, not speech. The law, he said, required law schools to provide space and access, but it did not require them to endorse the military’s views or to say anything at all.

He also said this was not a dispute in which the conduct — providing space and services — was inherently expressive or should be subjected to a higher standard used in such cases as in United States v. O’Brien (1968). Finally, he said the Solomon amendment does not pose a freedom of association problem: Military recruiters are simply present to conduct interviews; they are not trying to become part of the institution in the way that a gay man sought to be a Boy Scout troop leader as in Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000).

U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., applauds at the opening celebration of the Centennial of the U.S. Courthouse in Providence, Rhode Island, in 2008. Roberts has shown himself to be sensitive to First Amendment concerns. He wrote, “Speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and — as it did here — inflict great pain. On the facts before us, we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a Nation we have chosen a different course — to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate.” (AP Photo/Stephan Savoia, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Roberts has been sensitive to First Amendment concerns

In some of his opinions, Roberts has proven to be sensitive to First Amendment concerns. He wrote the Court’s opinion in United States v. Stevens (2010), invalidating a federal law that criminalized the creation or dissemination of images of animal cruelty. The government had argued that such images should be a new unprotected category of speech akin to child pornography. Roberts emphatically rejected that proposition, writing that the Court does not have “freewheeling authority to declare new categories of speech outside the scope of the First Amendment.” Roberts also wrote the Court’s opinion in Snyder v. Phelps (2011), ruling that the First Amendment prohibited the imposition of civil liability against the Westboro Baptist Church for their highly offensive picketing near the funeral of a slain serviceman.

In oft-cited language, Roberts wrote:

“Speech is powerful. It can stir people to action, move them to tears of both joy and sorrow, and — as it did here — inflict great pain. On the facts before us, we cannot react to that pain by punishing the speaker. As a Nation we have chosen a different course — to protect even hurtful speech on public issues to ensure that we do not stifle public debate. That choice requires that we shield Westboro from tort liability for its picketing in this case.”

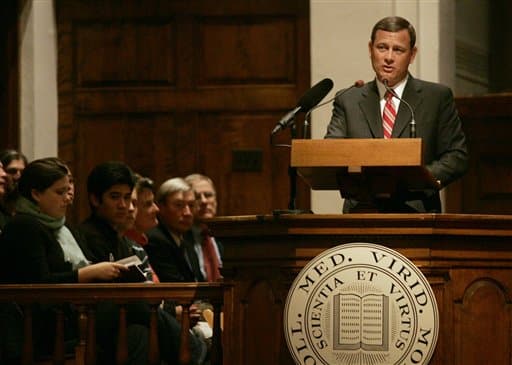

U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, Jr., right, speaks to the crowd at Middlebury College’s Mead Memorial Chapel in 2006 in Middlebury, Vermont. In the area of campaign finance, Roberts has proven to be a strong vote in favor of those asserting free-speech challenges to laws that limit campaign expenditures and contributions. He authored the Court’s opinion in McCutcheon v. FEC (2014), striking down aggregate limits on individuals’ campaign contributions. Roberts reasoned that the restrictions imposed a draconian restriction on pure political speech, writing, “The Government may no more restrict how many candidates or causes a donor may support than it may tell a newspaper how many candidates it may endorse.” (AP Photo/Alden Pellett, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Roberts has been a strong vote for limiting campaign contributions laws

In the area of campaign finance, Roberts has proven to be a strong vote in favor of those asserting free-speech challenges to laws that limit campaign expenditures and contributions. Roberts authored the Court’s majority opinion in Federal Election Commission v. Wisconsin Right to Life, Inc. (2007), ruling that a section of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 violated the First Amendment rights of a corporation that sought to air issue ads. He also authored the Court’s opinion in McCutcheon v. FEC (2014), striking down aggregate limits on individuals’ campaign contributions. Roberts reasoned that the restrictions imposed a draconian restriction on pure political speech, writing, “The Government may no more restrict how many candidates or causes a donor may support than it may tell a newspaper how many candidates it may endorse.”

However, Roberts also wrote the Court’s opinion in Williams-Yulee v. Florida Bar (2015), upholding a provision of the Florida Code of Judicial Conduct that prohibited judicial candidates from soliciting for campaign funds. He recognized that the law was a content-based law subject to strict scrutiny, but reasoned that the provision was a narrowly tailored way of addressing the state’s compelling interests in protecting the integrity of the judiciary and public confidence in the fairness and integrity of judicial proceedings.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2017. Stephen Wermiel is a professor of practice at American University Washington College of Law, where he teaches constitutional law, First Amendment and a seminar on the workings of the Supreme Court. He writes a periodic column on SCOTUSblog aimed at explaining the Supreme Court to law students. He is co-author of Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and The Progeny: Justice William J. Brennan’s Fight to Preserve the Legacy of New York Times v. Sullivan (ABA Publishing, 2014).