By the time Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. (1841–1935) retired from the Supreme Court in 1932, after serving for 29 years, he had become known as the Great Dissenter. He was viewed as a civil libertarian who protected the First Amendment from encroachments, particularly during World War I and the period of hostility to dissent that followed the war.

Holmes created the clear and present danger test

Holmes wrote some of the most significant free speech decisions ever handed down by the Court. In the process he attempted to identify the fine line between protected and unprotected speech with his clear and present danger test, in which he used the now classic example of an individual falsely shouting “Fire” in a theater as an example of speech that was “substantively evil.”

Holmes was born in Boston, Massachusetts, into a prominent, staunchly abolitionist family. After graduating from Harvard in 1861, he served with the Massachusetts 20th Volunteers during the Civil War. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1866. He returned to Harvard to teach legal history, constitutional law, and jurisprudence after a brief period of private practice in partnership with his brother. A compilation of Holmes’s Harvard lectures was published in 1881 as The Common Law. The Common Law, considered by many scholars to be the best book written on the American legal system, expounded Holmes’s legal philosophy, which he based on the notion that law is derived from human experience rather than logic.

In 1882 Holmes, a progressive Republican, accepted a position on the Massachusetts Supreme Court where he served for 20 years. Holmes helped to shape the state’s interpretations of libel and slander laws. He was named Massachusetts chief justice in 1899. In 1902 President Theodore Roosevelt named him to the Supreme Court, and the Senate unanimously confirmed him.

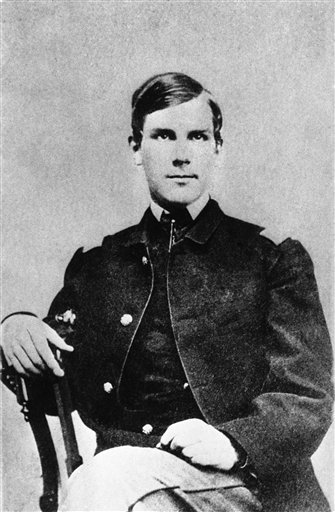

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes at the age of 21 as a captain in the Union Army during the Civil War in 1862. Holmes served throughout the conflict and was wounded three times. (AP photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Holmes did not begin his tenure as a First Amendment advocate

Holmes did not begin his tenure as a First Amendment advocate, assuming that role after more than a decade on the Court. His first significant experience with the First Amendment as a justice occurred with Patterson v. Colorado (1907), in which a newspaper editor was convicted of contempt after printing articles and cartoons depicting members of the Colorado Supreme Court in a derogatory manner. Writing for the majority, Holmes determined that no First Amendment issues were at issue because the amendment limited only the actions of the national government.

The Court addressed the constitutionality of a similar statute in Fox v. Washington (1915). In his majority opinion, Holmes rejected Jay Fox’s claim that his First Amendment rights had been infringed upon in his misdemeanor conviction for printing an article, “The Nude and the Prudes,” in praise of nudity.

Holmes advocated for First Amendment rights in sedition cases

Holmes began to take on the role of activist civil libertarian with two sedition cases that originated in the United States’ involvement in World War I. In Schenck v. United States (1919), Holmes delivered the majority opinion upholding the conviction of socialist Charles Schenck, who had been charged with violating the Espionage Act of 1917 by attempting to discourage draftees from responding to draft notices.

Acknowledging that interfering with the government’s ability to raise troops might constitute a legitimate exception to the First Amendment, Holmes introduced the clear and present danger test. Attempting to determine what forms of speech were unprotected by the First Amendment, Holmes suggested that it should be determined according to “whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” Those evils were defined as plotting the overthrow of the government, inciting riots, and destroying life and property.

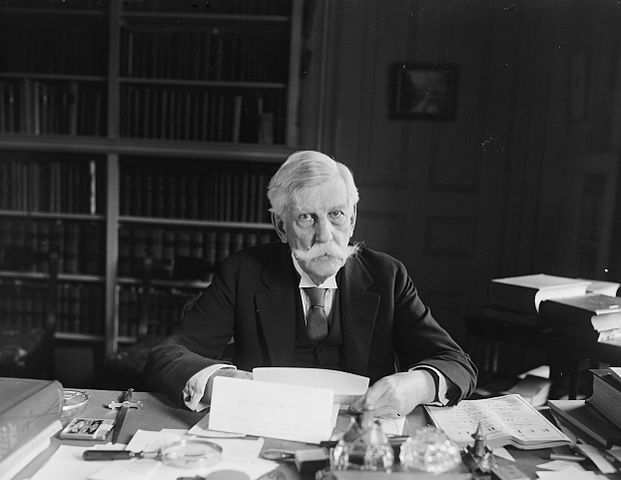

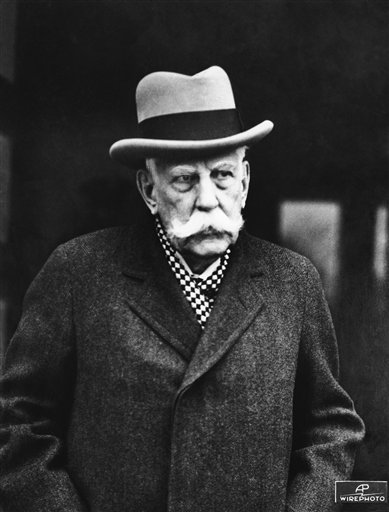

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1931. Holmes wrote some of the most significant free speech decisions ever handed down by the Court. In the process he attempted to identify the fine line between protected and unprotected speech with his clear and present danger test, in which he used the now classic example of an individual falsely shouting “Fire” in a theater as an example of speech that was “substantively evil.” (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Later that same year, in Abrams v. United States (1919), Holmes dissented, along with Justice Louis D. Brandeis, when the Court upheld the convictions of five petitioners also charged under the Espionage Act of 1917. In his dissent, Holmes stated that the principle of free speech remained the same during war time as in peace time; he reiterated his belief that congressional restraints on speech were permissible only when speech constituted a “present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about.”

Holmes continued to advocate for the clear and present danger test

By 1923 World War I had ended, and the mood of the Court had become more open on the issue of seditious speech. Such was the case when the Court agreed to hear Gitlow v. New York (reargued 1925). The case involved socialist Benjamin Gitlow, who had been accused of plotting to overthrow the government and had been convicted of criminal anarchy for distributing socialist literature. Although noting that Gitlow had not managed to encourage others to revolt, the Court upheld his conviction. Gitlow began the process of incorporating the First Amendment freedoms of speech and press and making them applicable to the states. While accepting the idea that the First Amendment should apply to the states, Holmes was joined by Brandeis in a dissenting opinion in which he argued that the words at issue posed no clear and present danger of inciting violent action.

In 1927 the Court returned to the issue of sedition in Whitney v. California, a case challenging California’s criminal anti-syndicalism law. The Court upheld the statute and acknowledged that Charlotte Whitney, as a member of a Communist organization, was in a position to attempt to carry out seditious activities in addition to talking about them. Acknowledging that Communist conspiracies were not protected by the First Amendment because those involved in the plot had both the intent and means to attempt an overthrow of the government, Holmes joined in Brandeis’s concurring opinion, which is oft-cited as an eloquent defense of free expression.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1931 in the Library at his Washington, D.C. home. For Holmes, the First Amendment provided the foundation for a democratic society. He was accordingly more likely to overturn state and federal convictions in this area than in the area of economic regulation. (AP photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Clear and present danger test eventually gave way to other tests

Although some justices never accepted the validity of Holmes’s argument, the Court applied the clear and present danger test in a number of cases. After the 1950s, however, the test was supplanted by the preferred position doctrine, which gave precedence to the First Amendment whenever it came into conflict with other rights. Ultimately, the Court treated First Amendment issues under the strict scrutiny test, which closely examines cases in which fundamental rights and those of protected classes according to race, religion, and ethnicity are at issue.

For Holmes, the First Amendment provided the foundation for a democratic society. He was accordingly more likely to overturn state and federal convictions in this area than in the area of economic regulation. In his notable dissents in Lochner v. New York (1905) and Hammer v. Dagenhart (1918), he was willing to uphold state maximum hours and child labor laws against claims that they violated reigning principles of laissez faire economics, which Holmes did not believe were incorporated in the Constitution.

This article was originally published in 2009. Elizabeth Purdy, Ph.D., is an independent scholar who has published articles on subjects ranging from political science and women’s studies to economics and popular culture.