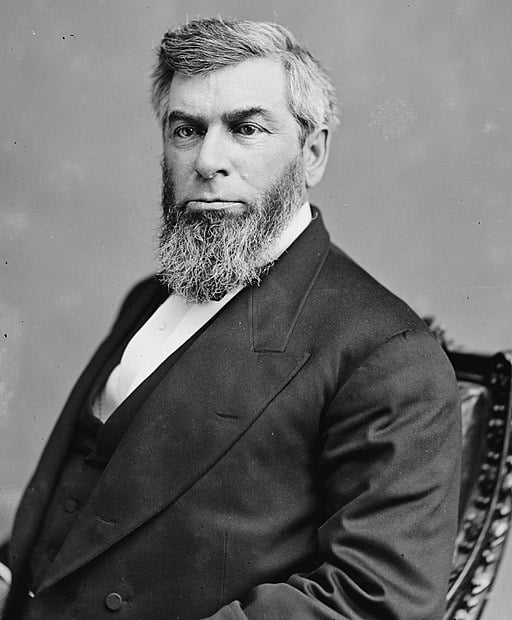

Morrison Remick Waite (1816-1888), the seventh chief justice of the Supreme Court, was born in Connecticut, the son of a lawyer who would become the state’s chief justice. After graduating from Yale, Waite read law under his father and migrated to Ohio where he studied under another lawyer before setting up his own practice.

After serving as a mayor, Waite was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives, but remained relatively obscure outside his state.

In something of a surprise, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed him in 1871 as a member of the Geneva Arbitration Tribunal, which settled U.S. claims against the British government for aiding the Confederate Navy by supplying the CSS Alabama and other warships that had attacked American merchant ships rather than adhering to its professed neutrality.

After Supreme Court justice Salmon Chase died, Grant eventually appointed Waite to the U.S. Supreme Court where he served from 1874-1888. (Grant had approached four other candidates who had declined his offer or withdrawn from consideration.)

With respect to states’ rights and the rights of African Americans, Waite’s jurisprudence was closer to that of Justice Roger Taney rather than to that of his immediate predecessor. Waite is regarded as a competent social and managerial leader of the court but was not as rhetorically gifted as some of his colleagues.

Waite participated in several First Amendment cases

As chief justice, Waite participated in a number of cases implicating First Amendment issues.

In Ex parte Curtis, 106 U.S. 371 (1882), he wrote the opinion prohibiting officials of the U.S. government from either requesting or receiving money for political purposes from other governmental employees. Dissenting justices thought that this interfered with First Amendment rights.

In United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876), Waite authored the decision rejecting arguments by families of the victims of the Colfax Massacre in Louisiana that the national government could protect against the actions of private individuals. Moreover, he continued to adhere to the doctrine that John Marshall had articulated in Barron v. Baltimore (1833) that the provisions in the Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, applied only to protecting citizen rights against actions by the national government and not those by the states. On a more positive note, his decision observed that “[t]he very idea of a government, republican in form, implies a right on the part of its citizens to meet peaceably for consultation in respect to public affairs and to petition for a redress of grievances.”

Waite wrote ruling that upheld law barring polygamy

In Reynolds v. United States, 98 U.S. 145 (1879), Waite wrote the majority opinion upholding a law prohibiting polygamy (a practice then associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints) against a challenge under the First Amendment’s right to free exercise of religion. He did so by distinguishing the permissible regulation of actions based on religious beliefs from the regulation of such belief itself.

On another matter, Waite issued the decision in Munn v. Illinois (1877) permitting states to regulate grain elevators and other businesses “affected with a public interest” over dissenters who thought this was improper interference with free enterprise. In another decision, in Minor v. Happersett, 88 U.S. 162 (1875), Waite upheld a state law that denied voting rights to women, a right that the national government did not guarantee until the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920.

When Waite died, President Grover Cleveland appointed Melville Fuller to replace him.

John R. Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.