In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, 597 U.S. ____ (2022), Justice Neil Gorsuch authored a consequential opinion for a 6-3 majority upholding the right of a public school football coach to offer a prayer on the 50-yard line after a game. The decision is likely to have far-reaching repercussions for future interpretations of the free exercise, establishment and free speech clauses of the First Amendment. The decision overturned rulings by a U.S. District Court and by the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Gorsuch’s majority opinion in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District and Justice Sonia Sotomayor’s dissent came to differing conclusions in part by emphasizing different facts and in part by presenting differing understandings of the relationship between the establishment and free exercise clauses.

Coach refuses to stop prayers at 50-yard line

The case involving coach Joseph Kennedy arose in the Bremerton School District in the state of Washington when it announced that it would not renew Kennedy’s coaching contract after he knelt in prayer at midfield after a game.

When he first became coach, Kennedy had given inspirational talks with religious content to students who had gathered after games and he had followed prior coaches in leading players and staff in prayer in pre-game locker room meetings. He had discontinued both practices when school officials warned that this violated the establishment clause. Kennedy however refused to discontinue offering a prayer at midfield and did so on three occasions while most students were engaged in other activities. Lower courts had ruled that the school could discipline him both because they believed that his action was governmental rather than merely private speech and because they believed that it took place at a time when he should have been supervising his players.

In interpreting the First and Fourteenth Amendments, Gorsuch argued that governments needed to pursue “neutral” and “generally applicable” principles. Because the school acted to restrict Kennedy’s actions because they were religious in nature while allowing other officials to call home or engage in other nonsupervisory activities after the game, its actions should be subject to strict scrutiny, the highest form of judicial review that courts use to evaluate the constitutionality of laws, regulations or other governmental policies under legal challenge.

Court: Prayer was not trying to convey a government message

In examining Kennedy’s free speech claims, Gorsuch cited Tinker v. Des Moines Independent School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969), which had upheld the rights of students to wear armbands protesting the Vietnam War, for the principle that neither teachers nor students shed their First Amendment rights at the schoolhouse gate. He further employed the tests developed in Pickering v. Board of Education of Township High School District, 391 U.S, 563 (1968), and Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410 (2006), to indicate that Kennedy’s speech was private as opposed to government speech because he was neither attempting to convey a government-created message nor requiring others to join him.

Gorsuch thought that the argument that Kennedy remained on duty as a role model went too far “by treating everything teachers and coaches say in the workplace as government speech subject to government control.” By such logic, he argued that government could “fire a Muslim teacher for wearing a headscarf in the classroom or prohibit a Christian aide from praying quietly over her lunch in the cafeteria.”

Court rejects Lemon test for church-state separation

In the face of opinions that sometimes stressed the tension among the clauses in the First Amendment, Gorsuch chose to interpret them as “complementary” rather than as “warring” provisions. By contrast, he believed that the lower courts had created a “vice between the Establishment Clause on one side and the Free Speech and Free Exercise Clauses on the other.” He associated such conflict with the three-part Lemon test. That test says establishment clause violations are found where laws:

- lacked a clear secular legislative purpose;

- had the primary effect of advancing or inhibiting religion; or

- promoted excessive entanglement between church and state.

He also was critical of what he described as the Lemon’s test “its endorsement test offshoot” and with attempts to identify how a “reasonable observer” might interpret such actions. He thought such an approach resembled capitulation to a “heckler’s veto” over any speech or action that others might find to be offensive.

Citing the court’s opinion upholding prayer in Town of Greece v. Galloway, 572 U.S. ____ (2014), Gorsuch chose to interpret the establishment clause through the lens of “original meaning and history.” He failed to find any evidence that coach Kennedy had coerced anyone to join him. Moreover, he noted that Kennedy had discontinued locker room prayers and post-game speeches with religious content. Instead of taking offense, those who might have heard Kennedy pray on the sidelines could learn to tolerate the speech and prayers of others.

Gorsuch said that any rule forbidding teachers from engaging in any religious speech would “be a sure sign that our Establishment Clause jurisprudence had gone off the tracks,” and was suppressing religious liberty rather than protecting it. He thus distinguished the case at hand from other cases involving prayer at public school functions such as Lee v. Weisman, 505 U.S. 577 (1992) (public prayer by clerics at school graduations), or Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe, 530 U.S. 290 (2000) (prayers broadcast over a school loud speaker system at games).

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a brief concurring opinion noting that the majority had neither decided how the rights of public employees might differ from the rights of private citizens with respect to the free exercise clause nor what burden an employer must show to burden such exercise. Justice Samuel Alito further noted that the Court had not decided on the standard to be applied had Coach Kennedy not had free moments to engage in private activities.

Dissent: Bremerton ruling conflicts with precedent

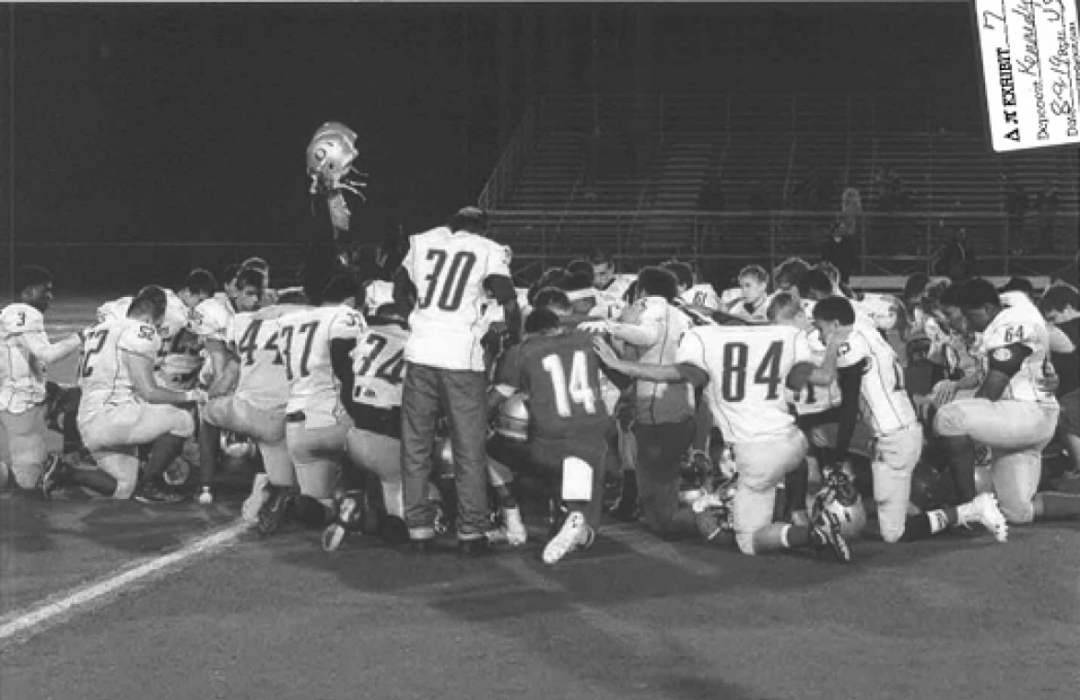

Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the dissent, illustrated with pictures of players joining coach Kennedy on the field as he prayed, which was joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan.

Sotomayor believed the decision ran counter to the line of cases that began when Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962), invalidated teacher-led prayer in public schools. Whereas the majority characterized Kennedy’s prayers as private, she thought that they were very public and that Kennedy had encouraged others to join, some of whom may have felt an element of coercion to do so.

Sotomayor was particularly concerned about Gorsuch’s substitution of a history and tradition test for the Lemon Test.

She believed that Kennedy’s demonstrative prayers had drawn him away from his responsibilities and that controversies over his activities had created a hostile atmosphere for those who might have refused to join. Whereas the majority had stressed the manner in which the coach had desisted from other religious activities, Sotomayor believed that reasonable observers would view his public prayers on the field as a continuation of such practices. His prayer was thus an attempt “to incorporate a public communicative display of the employee’s personal religious beliefs into a school event, where that display is recognizable as part of a longstanding practice of the employee ministering religion to students as the public watched.”

Sotomayor: Players would feel coerced into joining coach prayer

Sotomayor believed that the action violated the principle of governmental neutrality in religious matters, and that such violations were more dangerous in public school settings than elsewhere. She was particularly concerned about the possibility of indirect coercion in this context.

She pointed out that constitutional rights are not absolute and believed that there was sometimes implicit tension between the establishment and free exercise clauses. She concluded that the majority decision “elevates the religious rights of a school official, who voluntarily accepted public employment and the limits that public employment entails, over those of his students, who are required to attend school and who this Court has long recognized are particularly vulnerable and deserving of protection.”

This article was published June 27 2022. John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment.