Hugo Lafayette Black (1886–1971) served on the U.S. Supreme Court for 34 years and is widely considered to be one of the most influential justices of his time, even though his background and unusual path to the Court might have presaged a far more modest impact.

The son of a store owner of modest means, Hugo Black graduated from the University of Alabama and then served as a captain in the army during World War I. After the war, he was a police court judge in rural Alabama before being elected to the U.S. Senate in a landslide in 1926. In the Senate, he was a strong supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal — reportedly a factor in his nomination by Roosevelt to the Supreme Court to replace Justice Willis Van Devanter in 1937.

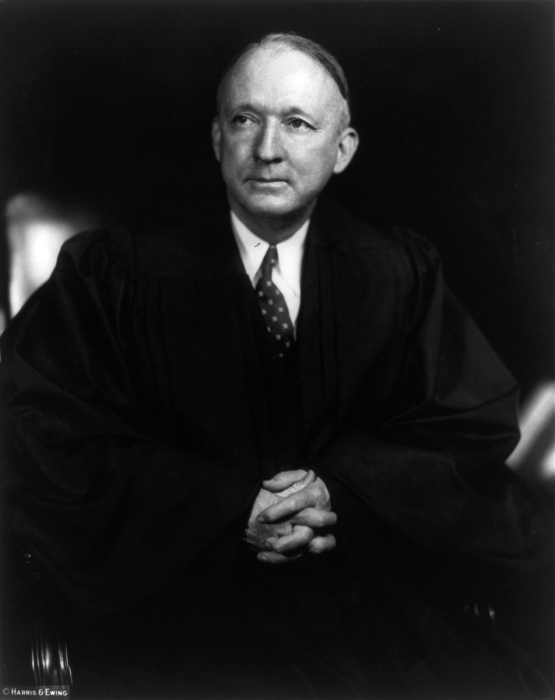

Hugo Black selected by Roosevelt for high court

Because Van Devanter and his conservative colleagues had been wreaking havoc on the New Deal, in 1937 Roosevelt announced a Court Reorganization Plan, but his “Court-packing” scheme was controversial and widely panned. Nevertheless, Senator Black initially supported the plan. When Van Devanter, the first in a string of resignations, left the Court, Roosevelt had a chance to change the composition of the Court, and Black was his first appointee.

Some controversy surrounded Roosevelt’s motivation for selecting Black. Some have argued that Roosevelt nominated Black to fulfill a particular agenda: to undermine the legitimacy of the Supreme Court in the wake of his battles with it. Choosing Black, a nondescript populist senator who would almost certainly be confirmed by his colleagues, might lessen the prestige of the Court.

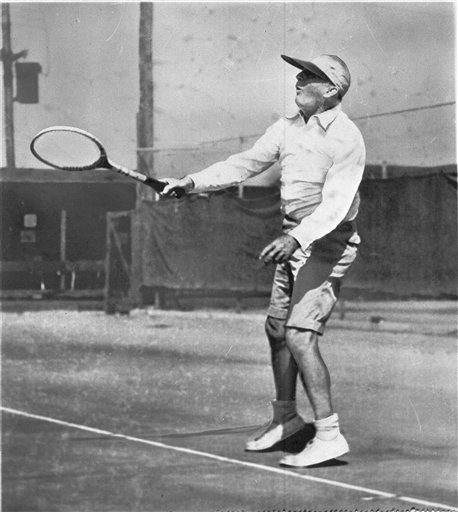

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black serves up during a tennis match at the St. Petersburg, Fla., Tennis Club in 1948. Although a former member of the Ku Klux Klan, Black renounced the Klan’s beliefs and became a strong supporter of civil rights during his time on the Court. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Two things, though, seemed fairly certain. First, Roosevelt wanted a supporter of the New Deal, and, second, he recognized that nominating a senator was likely to ensure a relatively easy confirmation. But instead of an immediate confirmation, the unwritten rule for nominations of senators at that point, the matter was turned over to the Judiciary Committee.

When his nomination finally made it to the floor of the Senate, Black was confirmed by a vote of 63-16.

But shortly after the confirmation, the public learned about Black’s past affiliation with the Ku Klux Klan.

On the eve of taking his seat on the Supreme Court, Black went public, explaining that membership in the Klan was a practical necessity to enter politics in the South (the KKK supported Black in his Senate campaigns).

Black became a strong supporter of civil rights

He went on to say that he had long since renounced the Klan’s beliefs and his membership. Black weathered the storm and eventually became a strong supporter of civil rights. In fact, it became the joke that “as a young man Hugo Black wore white robes and scared black people and as an older man, he wore black robes and scared white people.”

Black joined with his new colleagues on the Court — among them Felix Frankfurter and William Douglas — to uphold the regulatory schemes of the New Deal and strengthen the hand of the central government. Ultimately, the Court developed consistent doctrine in these areas, and then it began to turn its attention to civil rights and individual liberties. It was in these areas that Black made his most significant mark.

Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black, 71, and his bride Elizabeth Demeritte, 49, in Virginia, 1957. Black was an intellectual leader on the Court who often sparred with his colleagues. (AP Photo/Bob Schutz, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Black became an intellectual leader on the Court, often sparring with his colleagues Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson over important legal and constitutional issues. Indeed, although he was able to coexist with Frankfurter, his antipathy for Jackson was well known. Jackson, who had hoped to be elevated to chief justice, blamed Black for his presumed efforts to thwart that move.

Black was famous for carrying with him a worn copy of the Constitution and consulting it during conferences with his colleagues. He was considered a literalist or textualist, who believed that “Congress shall make no law” meant no law with respect to the First Amendment. He forcefully rejected the idea of substantive due process, which had been at the center of many of the battles between Roosevelt and the Court prior to Black’s appointment. Almost three decades later, this stance led him to reject the constitutional right to privacy.

Black led dialogue on incorporation of Bill of Rights

Black was in the vanguard of an emerging constitutional dialogue on the incorporation of the Bill of Rights to the states — a move he supported. He argued that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment had effected that application. Black’s dissent in Adamson v. California (1947) was his fullest discourse on this topic. Black maintained until his death that he was proudest of this opinion, although a majority of the Court, while eventually incorporating most provisions of the Bill of Rights through the process of selective incorporation, never adopted his perspective.

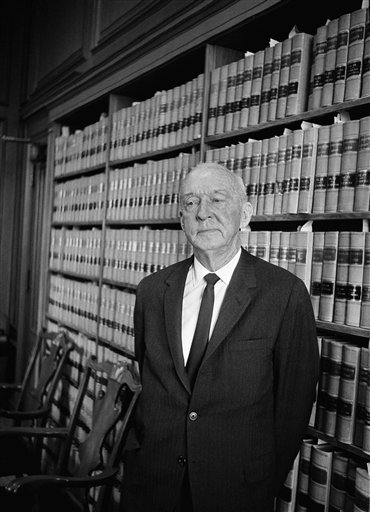

Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black in his office at the Supreme Court in 1966. Black was an absolutist who fully supported the incorporation of the Bill of Rights to the states through the due process clause of the 14th Amendment. (AP Photo/Charles Gorry, used with permission from the Associated Press)

On First Amendment issues, Black was considered an absolutist. In Dennis v. United States (1951) and similar cases, he dissented from the Supreme Court’s opinion upholding the conviction of leading U.S. Communists under the Smith Act.

But this absolutist stance created some problems for Black. Because he held that only pure speech received this level of protection, in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969) Black dissented from the Court’s decision to extend free speech protection to several students who wore black armbands to protest the U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Some observers have argued that this decision, coming near the end of Black’s career, was evidence of a growing conservatism in his decision making. But it is more likely that the apparent retreat was the result of the complexity of the later free expression cases and the nontraditional extensions of the meaning of speech.

Black rejected prior restraints on publishing by the press

Black’s support for freedom of the press was similar to his support for freedom of speech. He authored one of the opinions in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971) rejecting prior restraint of the Pentagon Papers.

He concurred in Justice William J. Brennan Jr.’s opinion in New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1965) raising the bar for public officials to prove libel.

Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court, Hugo L. Black, right, and Earl Warren are seen on Black’s 80th birthday, Feb. 24, 1966, in Washington. On First Amendment issues, Black used his absolutist stance and supported a relatively strict separation of church and state. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Black led important rulings on establishment clause

Black had been raised as a Baptist at a time when that denomination was often associated both with anti-Catholicism and a strict adherence to the separation of church and state. Although he taught Sunday school at a Baptist church in Birmingham for many years, Black, who attended a Unitarian church (albeit infrequently) during his years on the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington, D.C., seemed to value Christianity as much for its ethical and civilizing tendencies, including its support for tolerance, as for the truth of its creeds. Like Thomas Jefferson, whom he so admired, Black believed that one’s religion was a highly personal matter. Black served on the board of what later became Americans United for Separation of Church and State (Sekulow, 2006, xvii).

Black's views on strict separation of church and state were reflected in some of the most important decisions in the establishment clause area, including in Everson v. Board of Education (1947), which incorporated the establishment clause to the states, and in Engel v. Vitale (1962), which disapproved of teacher-led prayer in the public school classroom. Black’s evocation of Jefferson’s analogy of the wall of separation of church and state in the former case was particularly influential on case law of his day.

Black's support of civil rights cost him popularity in his native Alabama. By contrast, Black was the author of the controversial opinion in Korematsu v. United States (1944), which supported the government’s internment of Japanese Americans in World War II.

Black resigned from the Court in 1971. Within a week, he suffered a stroke and died a few days later. President Richard Nixon appointed Lewis F. Powell Jr. to take Black’s seat on the Court.

This article was originally written in 2009. Richard L. Pacelle, Jr. is professor and department head in Political Science at the University of Tennessee. Pacelle’s primary research focus is the Supreme Court. His research includes concerns with policy evolution particularly regarding the First Amendment and the role of policy entrepreneurs in the judiciary, Supreme Court agenda building and decision-making, and inter-branch relations.