Officially titled “History of U.S. Decision-Making in Vietnam, 1945–68,” the Pentagon Papers are a study of the origins and development of the Vietnam War.

They were commissioned in June 1967 by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara after he had developed doubts about the wisdom of that war. They became the subject of a major Supreme Court case, New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), regarding censorship and freedom of the press.

Pentagon Papers leaked to press by author who opposed the Vietnam War

The authors of the papers were granted access to numerous classified documents but were not permitted personal interviews. Work continued after McNamara was replaced by Clark Clifford and ended shortly after President Richard M. Nixon took office. Fifteen copies of the 47-volume top secret study were distributed. Although President Lyndon B. Johnson used parts in writing his memoirs, neither McNamara nor Nixon’s secretary of defense Melvin Laird read them.

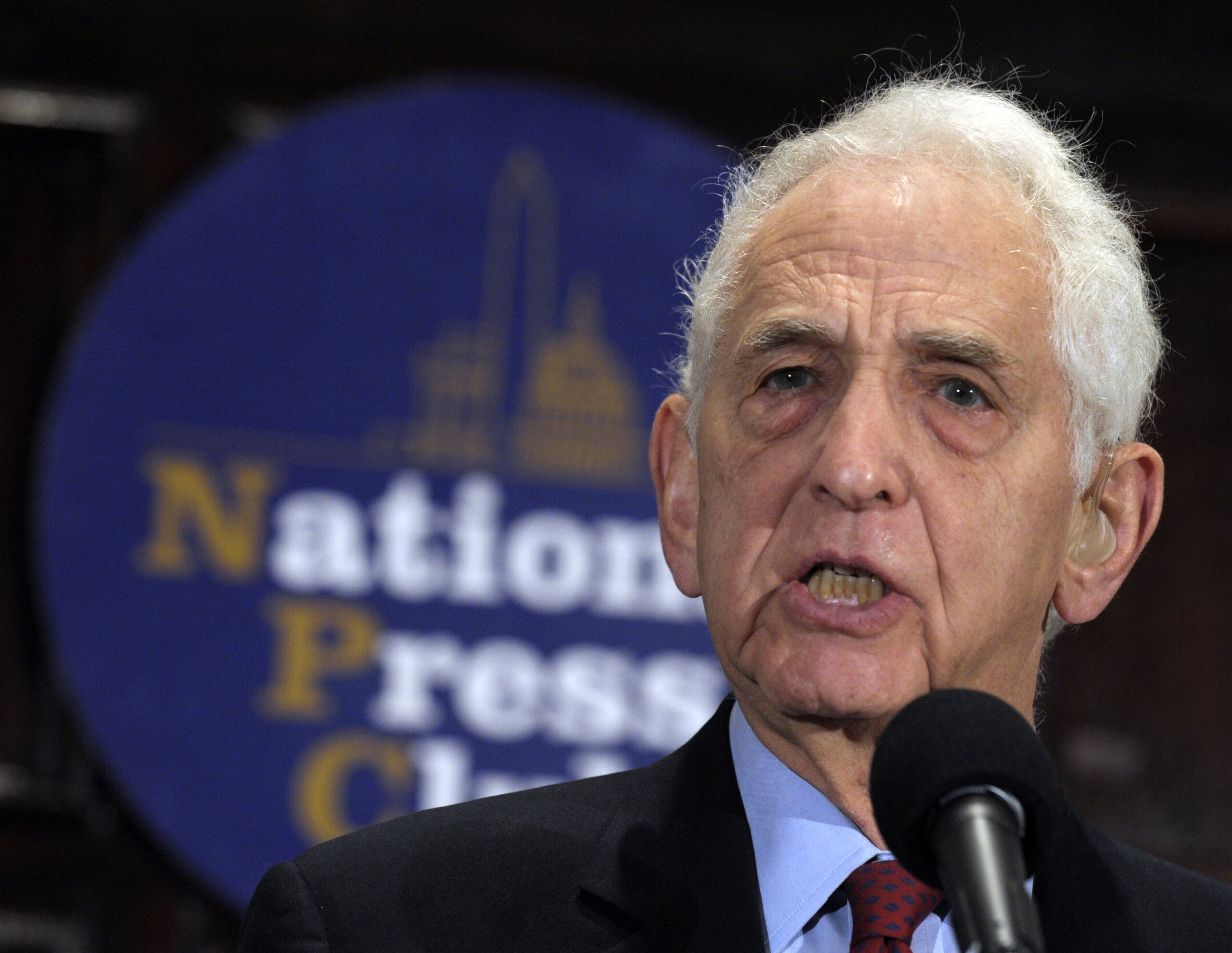

What made the Pentagon Papers the center of national attention was the obsession of one of the authors, Daniel Ellsberg.

After he had spent two years working alongside the military in Vietnam, Ellsberg’s support for the war turned to staunch opposition. Hoping that if members of the public learned what the study revealed, they would have a similar conversion, he began a campaign to make the papers public. When efforts to do this through official channels failed, in March 1971 he turned over a copy to Neil Sheehan of the New York Times, holding back four volumes concerning negotiations in order not to interfere with ongoing efforts.

Nixon administration sought injunction to prevent publication

After a lengthy examination of the material and fierce internal debate, the Times decided to publish the study as a nine-part series beginning June 13.

In this June 21, 1971 file photo, Katharine Graham, left, publisher of The Washington Post, and Ben Bradlee, executive editor of The Washington Post, leave U.S. District Court in Washington after getting the go-ahead to print the Pentagon Papers on Vietnam. Later, the U.S. Court of Appeals extended the ban against publishing the secret documents for one day. They eventually prevailed at the Supreme Court, which said the government did not meet the “heavy burden” of proof required for prior restraint of the press. (AP Photo, used with permission from The Associated Press.)

The Nixon administration filed a lawsuit in U.S. district court seeking an injunction to halt further publication after the newspaper declined a request to do so voluntarily. Ellsberg then gave a copy to the Washington Post, which began a similar series on June 18, resulting in a second lawsuit. The judges in both cases ruled against the government’s request for a temporary restraining order, but in each case the ruling was stayed to permit an appeal.

After the two circuit courts reached conflicting results, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case immediately rather than waiting for its October term. Because the Supreme Court announced its 6-3 decision allowing publication only two weeks after the case had been filed, there was no time to develop a consensus position.

Instead the majority simply voted for a brief per curiam opinion stating that the government had failed to meet the “heavy burden” of proof required for prior restraints, accompanied by separate opinions by each of the nine justices.

Justice Department considered criminal charges against press

With the injunctions lifted, the newspapers completed their series. Despite selling a million copies, the Times book version of the study generated little additional debate about the Vietnam War. When the official government version was published in September, only 500 copies sold.

Memos released in 2022 showed that the Department of Justice considered bringing criminal charges against the newspapers and even individual reporters, but ultimately decided against it. The department did charge Ellsberg, but the charges were eventually dismissed due to government misconduct. In 1994 Whitney North Seymour Jr., who had argued for the government in district court, conceded that there was no “trace of a threat to national security from the publication.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Bruce Altschuler is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at SUNY Oswego and the author or co-author of eight books, most recently Lights, Camera, Execution! Cinematic Portrayals of Capital Punishment. His numerous scholarly articles include “Is the Pentagon Papers Case Relevant in the Age of WikiLeaks?,” Political Science Quarterly, Fall 2015.