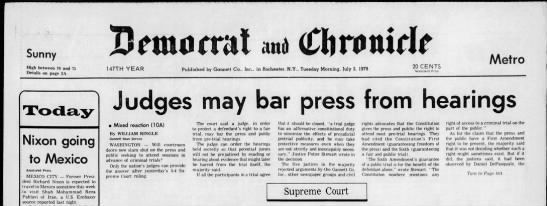

The Supreme Court ruled in Gannett Co. v. DePasquale, 443 U.S. 368 (1979), that the Sixth Amendment right to a “public trial” belongs to the defendant in a criminal case and does not guarantee the public or the press access to pretrial hearings or even to trials.

The decision and the controversy it caused ironically set the stage for the ruling a year later in Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v. Virginia (1980) holding that the First Amendment creates a right of access for the press and public to criminal trials.

Closed trials upheld by court

Gannett involved the 1976 disappearance of Wayne Clapp while on a boat on Seneca Lake near Rochester, New York. The incident received substantial press coverage. Two men arrested and charged with his murder moved to suppress statements and other evidence prior to trial and asked the judge to bar the press and the public from the pretrial hearing. The trial judge closed the hearing, rejecting a subsequent complaint from a newspaper reporter whose paper was owned by Gannett. The highest state court, the New York Court of Appeals, upheld the closure.

In a 5-4 vote, the Supreme Court affirmed, ruling that where a criminal defendant and prosecutor both favor closure of a pretrial proceeding, the Sixth Amendment does not create any public right to attend. Justice Potter Stewart’s opinion for the Court suffered from three problems that created confusion and ultimately led to its demise.

- Stewart did not limit his Sixth Amendment discussion to pretrial hearings and spoke more broadly of entire trials.

- He stated that a pretrial closure does not violate the public’s or media’s First Amendment right, although this argument was not fully explained or developed.

- Three of the five justices in the majority — Chief Justice Warren E. Burger and Justices Lewis F. Powell Jr. and William H. Rehnquist — wrote concurring opinions differing from Stewart’s in the breadth and basis for the decision.

Ruling resulted in media and judicial backlash

Burger argued that the ruling covered pretrial proceedings only. Powell asserted that there is a First Amendment right of access. Rehnquist held that there is no right of access under any part of the Bill of Rights. Justice Harry A. Blackmun dissented, relying on the history of open trials to argue that the Sixth Amendment protects a right of access to trials and pretrial proceedings by the press and the public.

The ruling led dozens of judges around the country to grant requests to close pretrial hearings and entire trials. The media outcry over this trend, in turn, led to the unusual spectacle of four justices — Chief Justice Burger and Justices Blackmun, Powell and John Paul Stevens — explaining or commenting off the bench during summer 1979 on the scope of the Gannett ruling and on the reaction to it. At the end of the summer, the Court granted review to the Richmond Newspapers case.

This article was originally published in 2009. Stephen Wermiel is a professor of practice at American University Washington College of Law, where he teaches constitutional law, First Amendment and a seminar on the workings of the Supreme Court. He writes a periodic column on SCOTUSblog aimed at explaining the Supreme Court to law students. He is co-author of Justice Brennan: Liberal Champion (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2010) and The Progeny: Justice William J. Brennan’s Fight to Preserve the Legacy of New York Times v. Sullivan (ABA Publishing, 2014).