Harry Andrew Blackmun (1908–1997) served as an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court from 1970 to 1994. He is best known for writing the majority opinion in Roe v. Wade (1973) that overturned most state abortion laws. That decision was built on Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which formulated a right of privacy based in part on emanations from the First Amendment.

Blackmun was an architect of the Court’s commercial speech doctrine

Appointed by President Richard Nixon with the strong approval of his former childhood friend Chief Justice Warren E. Burger, Blackmun was expected to be a thoroughly conservative justice. In fact, early in Blackmun’s tenure on the Court he and Burger were dubbed the “Minnesota twins.” However, Blackmun’s rulings, including those in First Amendment cases, became increasingly liberal as he sat on the Court, displeasing Burger.

Justice Blackmun is considered an architect of the Court’s commercial speech doctrine, which concerns whether business-related expression enjoys constitutional protection similar to that extended to political speech. In Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), Blackmun wrote the opinion that held that a Virginia newspaper was within its First Amendment rights in publishing an advertisement for legal abortions available in New York.

In 1976 he wrote for the majority in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. in which the Court held that society had a “strong interest in the free flow of commercial information” and that even speech that was bought and paid for enjoyed First Amendment protection. The Court acknowledged, however, that regulation of commercial speech was permissible to ensure that it was accurate as well as free. Justice Blackmun also wrote the opinion in Bates v. State Bar of Arizona (1977) that allowed lawyers to advertise their services and fees.

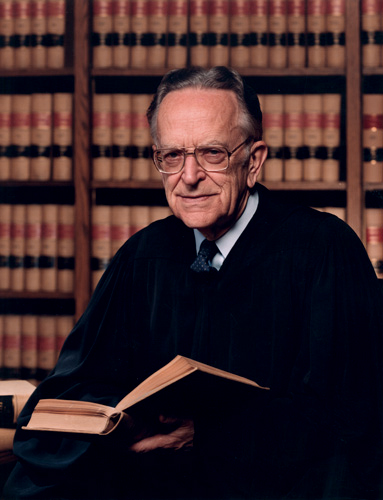

Supreme Court Justice Harry Blackmun has his robe adjusted by his wife after taking his oath to join the high court 1970. Blackmun is considered an architect of the Court’s commercial speech doctrine, which concerns whether business-related expression enjoys constitutional protection similar to that extended to political speech (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Blackmun wrote opinions in First Amendment cases

Blackmun was one of three justices who dissented in the Court’s decision in New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), which used the strong presumption against prior restraint to allow publication of the Pentagon Papers. He and the other two dissenters were particularly concerned about the haste with which the Court decided the case.

In 1989 Blackmun agreed with the majority opinion by Justice William J. Brennan Jr. in the flag-burning case Texas v. Johnson. The opinion held that Gregory Lee Johnson’s conviction under a Texas law that prohibited the desecration of the American flag violated his right to free expression. Johnson, who had burned the flag during a nonviolent protest at the 1984 Republican National Convention, clearly intended to convey a political statement.

Blackmun joined the Court in stating, “If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea offensive or disagreeable.” However, Blackmun wrote in his concurrence that he had struggled with the case and found it “difficult and distasteful.”

Several years later, the Court considered a St. Paul, Minnesota, law that prohibited the display of symbols that aroused “anger, alarm, or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion, or gender.” A young man had been charged under the ordinance for burning a cross on a black family’s lawn. In R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992), the majority struck down the law on First Amendment grounds. Blackmun concurred, but he wrote separately that he did not believe it violated the First Amendment to prohibit “hoodlums from driving minorities out of their homes by burning crosses on their lawns.” He was concerned that the people of St. Paul were prevented from outlawing the “race-based fighting words” that threatened their community.

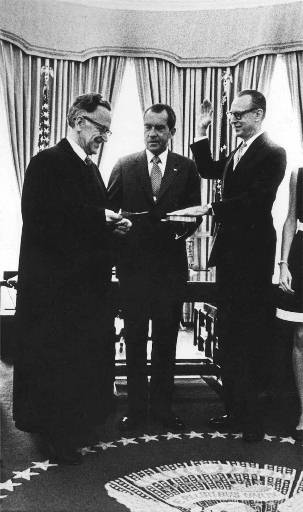

President Nixon, center, holds the Bible as Associate Supreme Court Justice Harry A. Blackmun, left, administers the oath of office to John Irwin II, as Undersecretary of State 1970. Blackmun was involved with many First Amendment cases, including Texas v. Johnson (1989) which involved flag desecration. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Blackmun was involved in First Amendment religion cases

Among several cases that tested the establishment clause of the First Amendment, the Court considered whether a nativity scene could be placed inside a courthouse. In County of Allegheny v. American Civil Liberties Union (1989), Blackmun wrote the majority opinion holding that a creche alone, without other holiday decoration, constituted an endorsement of Christian doctrine. He also pointed out that governments could celebrate Christmas in secular ways without violating the First Amendment. For example, the Court found such an acceptable arrangement at another public building where the display included a Christmas tree, a menorah, and a sign proclaiming liberty.

In free exercise cases, Blackmun joined Justice Brennan’s dissent in O’Lone v. Estate of Shabazz (1987). They argued that Muslim prisoners were deprived of fundamental First Amendment rights when they were denied the opportunity to participate in Friday prayers because the administrators claimed it would cause discipline problems. The dissenters demanded that government agencies prove they had compelling reasons to limit the free exercise of religion.

In Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990), the Court ruled that depriving a Native American who had used peyote at a religious ceremony of his unemployment benefits did not violate the free exercise clause. Justice Blackmun dissented, criticizing the state for its unwillingness to make an exception in its “war on drugs” for religious ceremonies, especially because its claim that ritual peyote would encourage drug use and trafficking was “purely speculative.” Such hypothetical harm hardly justified the restriction of a constitutional right.

This article was originally published in 2009. Mary Welek Atwell is Professor Emerita of Criminal Justice at Radford University. She is the author of five books and numerous articles about legal and justice issues. She holds a PhD from Saint Louis University.