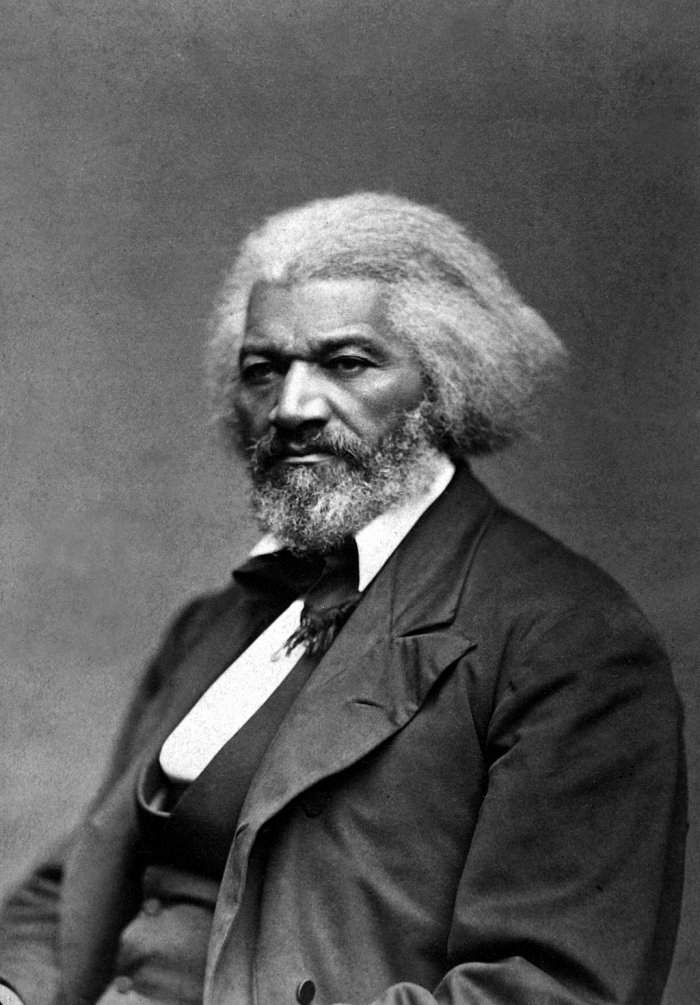

Frederick Douglass (1818-1895), was born on a Maryland plantation as a slave. He learned to read and escaped to become one of America’s greatest orators.

He worked with abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and others, published anti-slavery tracts, and wrote the Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which he first published in 1845 and which sold widely. He subsequently published related titles including My Bondage and My Freedom (1855) and the Life and Times of Frederick Douglass (1882).

Douglass believed freedom of speech essential to abolishing slavery

Douglass believed that his own path to freedom had begun with his own literacy, and he was convinced that the spread of literacy and the exercise of freedom of speech and assembly was essential to the success of abolitionism. Douglass believed that the right to liberty was a natural right, which had been clearly articulated in the Declaration of Independence. Disagreeing with Garrison, Douglass further believed that those who wrote the U.S. Constitution had intended to put slavery on a course of ultimate extinction.

On Dec. 10, 1860, just months before the beginning of the Civil War, Douglass gave a speech in Boston where, a week before, a mob had disrupted a speech entitled “How Shall Slavery Be Abolished?” Douglass observed that “gentlemen” had taken part in the riot, and the mayor had ignored requests to intervene to protect the speaker who became unable to express his views.

Right to free speech ‘is the dread of tyrants’

Douglass lamented that instead of protecting the speaker, the authorities had chosen to cast aspersions on the nature of his speech, thus parting with an earlier statesman from Massachusetts:

No right was deemed by the fathers of the Government more sacred than the right of speech. It was in their eyes, as in the eyes of all thoughtful men, the great moral renovator of society and government. Daniel Webster called it a homebred right, a fireside privilege. Liberty is meaningless where the right to utter one’s thoughts and opinions has ceased to exist. That, of all rights, is the dread of tyrants. It is the right which they first of all strike down. They know its power. Thrones, dominions, principalities, and powers, founded in injustice and wrong, are sure to tremble, if men are allowed to reason of righteousness, temperance, and of a judgment to come in their presence. Slavery cannot tolerate free speech. Five years of its exercise would banish the auction block and break every chain in the South. They will have none of it there, for they have the power. But shall it be so here? (Douglass 1860)

Douglass continued to say that “There can be no right of speech where any man, however, lifted up, or however humble, however young, or however old, is overawed by force, and compelled to suppress his honest sentiments.”

Right to speak is accompanied by the ‘right to hear’

In a point that may be applied to present-day controversies where crowds try to drown out speakers with whom they disagree, Douglass pointed out that the right to speak was accompanied by “the right to hear.” (See Right to Receive Information and Ideas)

He elaborated: “To suppress free speech is a double wrong. It violates the right of the hearer as well as those of the speaker. It is just as criminal to rob a man of his right to speak and hear as it would be to rob him of his money.” He observed that “When a man is allowed to speak because he is rich and powerful, it aggravates the crime of denying the right to the poor and humble.” Douglass further explained that “A man’s right to speak does not depend upon where he was born or upon his color. The simple quality of manhood is the solid basis of the right—and there let it rest forever.”

Right to speech especially important to the oppressed

In 1854, Douglass had gone to Chicago to give a speech on the Kansas-Nebraska Bill. The bill was introduced by Illinois Democrat Stephen A. Douglas and would permit the voting members of each territory (even those above the line originally designated as free by the Missouri Compromise of 1820) to decide for themselves whether they would allow slavery. In this speech, in which he played on the similarity of his last name to the Senators,’ Douglass had said that “The right of speech is a very precious one, especially to the oppressed.”

He noted that Senator Douglas considered himself to have been abused when he had been shouted down as he attempted to give a speech. After specifically stating that he did not approve of such a mob veto, Douglass observed that “I am for free speech as well as for freemen and free soil; but how ineffably insignificant is this wrong done in a single instance, and to a single individual, compared with the stupendous iniquity perpetrated against more than three millions of the American people, who are struck dumb by the very men in whose cause Mr. Senator Douglas was there to plead” (Douglass 1854).

Observing that “A free press and a free gospel, are as hostile as fire and gunpowder—separation of explosion, are the only alternatives,” Douglass pointed out that advocates of slavery had sought to suppress anti-slavery sentiments throughout the South. He may also have been thinking of the gag orders, which Congress had approved and which John Quincy Adams had fought so hard to repeal, to prevent consideration of slave petitions.

In the end, Douglass argued that “Truth is eternal,” and that “Such a truth is man’s right to freedom” (Douglass 1854).

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in February, 2020.