When Congress proposed the First Amendment, it was not proposing new rights but stating and consolidating rights to which the people were already accustomed.

Declaration and Resolves opposed Intolerable Acts that infringed upon rights

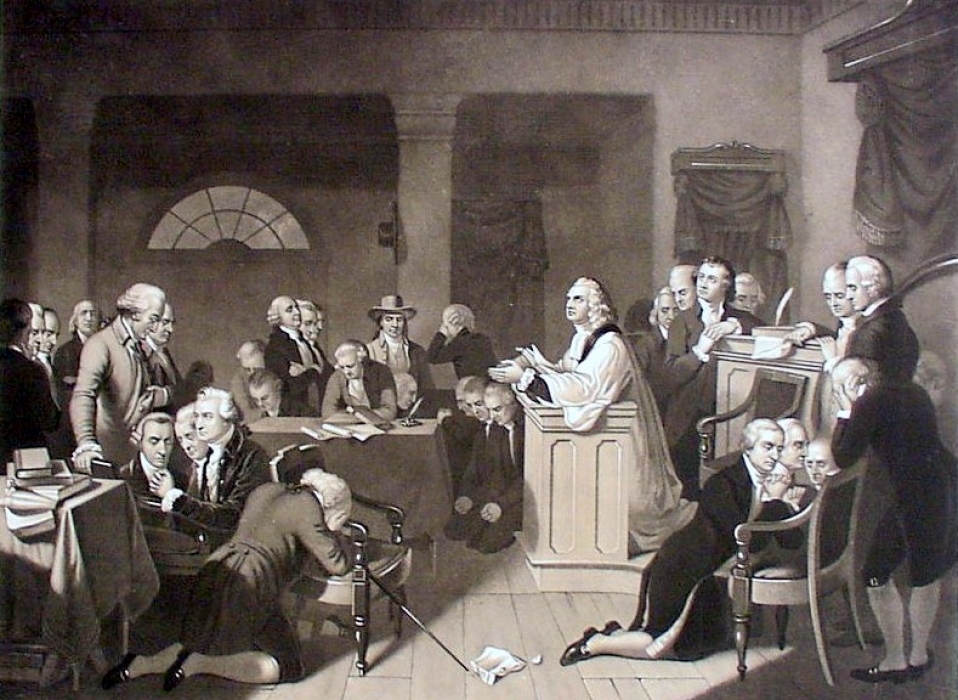

Evidence of this is found in the Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress, issued on October 14, 1774, in response to a series of measures enacted by Britain punishing the colonies for their opposition to taxes and referred to as the so-called Intolerable Acts.

In these resolutions, the colonies announced their desire to see that “their religion, laws, and liberties may not be subverted” and traced their rights to three sources — “the immutable laws of nature, the principles of the English constitution, and the several charters or compacts.”

Resolution 8 foreshadowed First Amendment rights

Resolution 8 — approved unanimously by the states represented (that is, excluding Georgia) — foreshadowed a right that would later be included in the First Amendment in providing that the colonists “have a right peaceably to assembly, consider of their grievances, and petition the king; and that all prosecutions, prohibitory proclamations and commitments for the same, are illegal.”

In addition, concerned about an established church, the delegates listed among the acts that they wanted repealed “the act passed … for establishing the Roman Catholic religion, in the province of Quebec.”

Supreme Court Justice Hugo L. Black would later cite Congress’s resolution relative to the right of peaceable assembly and petition in his dissent in Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952), which deals with group libel.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.