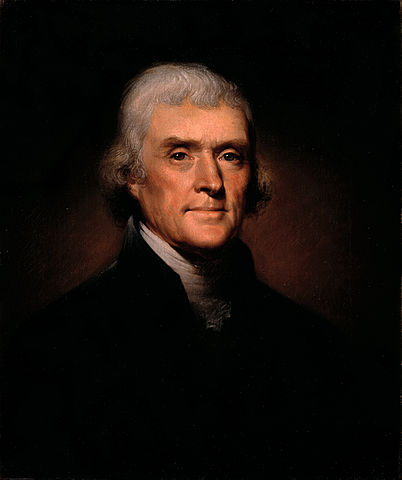

In an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut, then-president Thomas Jefferson highlighted the “wall of separation” metaphor previously utilized by Roger Williams, who had referred to the “wall of separation between the garden of the Church and the wilderness of the world” (Carter 1992, 116).

Jefferson explained his understanding of the First Amendment’s religion clauses as reflecting the view of “the whole American people which declared that their legislature should ‘make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ thus building a wall between church and State.”

The Supreme Court first quoted Jefferson’s reference in Reynolds v. United States (1879), a case in which the Court rejected the claim that the First Amendment’s protection of religious liberty exempted members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from the prohibition of polygamy due to their religious belief (at that time, but no longer) in the duty of polygamy.

Court used ‘wall of separation’ metaphor to announce strict separation of church, state

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), which first applied the First Amendment’s establishment clause to the states, the Supreme Court relied on Jefferson’s metaphor in announcing a strict standard of separation between church and state.

Justice Hugo L. Black concluded his opinion for the Court’s majority with the pronouncement that “[t]he First Amendment has erected a wall between church and state. That wall must be kept high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach. New Jersey has not breached it here.”

The Court, in this case, found no violation of the establishment clause by the state of New Jersey in its providing transportation for students attending Catholic parochial schools, which struck several dissenting justices as inconsistent with a wall of strict separation. Ever since Everson, there has been ongoing debate not only over how strictly to apply the wall of separation in particular cases, but whether that metaphor accurately reflects the meaning of the religion clauses.

‘Wall of separation’ meaning arose out of struggle for religious liberty in Virginia

While Jefferson’s letter did not elaborate the meaning of wall, the Everson opinion found continuity of meaning beginning with the preconstitutional struggle for religious liberty in Virginia, led by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison.

In 1784 the Virginia legislature had before it a bill to renew the tax levied to support the established state church, namely the Anglican Church.

Madison wrote his famous “Memorial and Remonstrance” against the law, and the legislature let the tax renewal die. Instead, it adopted the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786), which Jefferson had originally written. Black’s Everson opinion linked Virginia history, the establishment clause, and Jefferson’s later use of the phrase a wall of separation between church and state.

In an 1802 letter to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut, then-president Thomas Jefferson highlighted the “wall of separation” metaphor previously utilized by Roger Williams, who had referred to the “wall of separation between the garden of the Church and the wilderness of the world.” (Image via Wikimedia Commons, painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1800, public domain)

Rehnquist attacked court’s reliance on ‘wall of separation’ to define Establishment Clause

The strongest challenge to the Court’s reliance on Jefferson’s metaphor to interpret the establishment clause came from then-associate justice William H. Rehnquist in his dissent in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985).

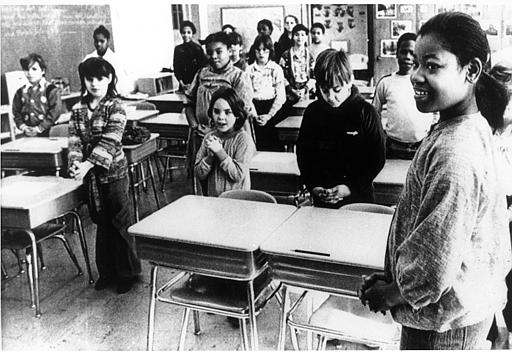

The Court’s majority found an Alabama statute that provided for public schools to observe a minute at the start of each day “for meditation or voluntary prayer” violated the establishment clause. The statute originally had mentioned only meditation, but had been amended to add the words “or voluntary prayer.”

Justice Rehnquist attacked the Court’s reliance on Jefferson’s understanding of the religion clauses, saying,“ There is simply no historical foundation for the proposition that the Framers intended to build the ‘wall of separation’ that was constitutionalized in Everson [v. Board of Education].” Rehnquist added that the Court’s establishment clause jurisprudence “has been expressly freighted with Jefferson’s misleading metaphor for nearly 40 years.”

Court has considered whether government can assist churches under First Amendment

Despite Everson’s endorsement of a strict wall of separation, the Supreme Court has struggled with what violates that separation. The words of the establishment clause specify “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion.”

At minimum, that prevents Congress from establishing a national church, just as Virginia prohibited a state-established church. However, the question remains if this means that government can make no law that has the effect of assisting a church or religion.

The strongest challenge to the Court’s reliance on the “wall of separation” metaphor to interpret the establishment clause came in a dissent in Wallace v. Jaffree (1985), a case that invalidated a minute for voluntary prayer at the beginning of the day. Justice William Rehnquist said that the Court’s establishment clause jurisprudence “has been expressly freighted with Jefferson’s misleading metaphor for nearly 40 years.” In this photo,Terri Thompson, 11, leads her fourth grade class in a short prayer at the start of the day in

Supreme Court has indicated strict separation between church and government is not required

Since Everson the Court has adopted a variety of approaches to the wall of separation.

These have been alternatively reflected in tests applied by the Court to the establishment clause, with occasional statements indicating that strict separation is not required, and with attempts to balance concerns over the establishment clause with concern for the free exercise of religion.

In Sherbert v. Verner (1963), the Court held that the free exercise clause required state accommodations for religious exercise, in this case the needs of a Seventhday Adventist to worship rather than work on Saturdays.

Jefferson thought ‘wall of separation’ applied to federal government only

In contrast, more recent cases like Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990) have held that the free exercise clause does not require religious exemptions from laws of general application; the Court has also said that states may allow them.

The Bill of Rights was proposed and ratified as a restraint against the federal government only, as Chief Justice John Marshall ruled in Barron v. Baltimore (1833). Despite Jefferson’s role in Virginia and his reference to a wall of separation as applied to the First Amendment, he nevertheless agreed that the federal law had no effect on state laws respecting religion. Thus, in his second inaugural address as president, Jefferson stated that religion “must then rest with States, as far as it can be in any human authority.”

Jefferson’s thinking aside, before Everson and culminating in the 1960s, the Court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause as making almost all provisions of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states. The First Amendment, uniquely among the amendments of the Bill of Rights, specified only that “Congress shall make no law. . . .” It has often been debated whether that limitation indicated that the Fourteenth Amendment does not incorporate provisions of the First Amendment.

Regardless, as a result of Everson, almost all of the federal cases invoking the wall of separation of church and state have been decided against state laws.

This article was originally published in 2009. John S. Baker, Jr. is a Visiting Professor of the Georgetown Center for the Constitution.