Yellow journalism usually refers to sensationalistic or biased stories that newspapers present as objective truth.

Established late 19th-century journalists coined the term to belittle the unconventional techniques of their rivals. Although Eric Burns (2006) demonstrated that the press in early America could be quite raucous, yellow journalism is generally perceived to be a late 1800s phenomenon full of lore and spin, fact and fiction, tall tales, and large personalities.

Yellow journalism marked by sensationalist stories, self-promotion

William Randolph Hearst, publisher of the New York Journal, and his arch-rival, Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, are credited with the creation of yellow journalism.

Such journalism had the following characteristics:

- the use of multicolumn headlines, oversized pictures, and dominant graphics;

- front-page stories that varied from sensationalist to salacious in the same issue;

- one-upmanship, or the scooping of stories, only later to be embarrassed into retractions (usually by a competing publication);

- jingoism, or the inflaming of national sentiments through slanted news stories, often related to Civil War;

- extensive use of anonymous sources by overzealous reporters especially in investigative stories on “big-business,” famous people, or political figures;

- self-promotion within the news medium; and

- pandering to the so-called hoi polloi, especially by using the newspaper layout to cater to immigrants for whom English was not their first language.

Conservative press organized boycott against Hearst and Pulitzer newspapers

The conservative press thought these characteristics amounted to misconduct in the gathering of news and launched a boycott of both newspapers.

The boycott was successful in excluding the two newspapers from the stands in the New York Public Library, social clubs, and reading rooms, but it only served to increase readership among average citizens who rarely frequented such establishments.

Overall, the boycott backfired. Circulation for both newspapers increased, and Hearst purchased other newspapers and insisted on the use of the same techniques in other cities.

The conservative press was itself not above printing the occasional fantastical story. Moreover, within ten years, almost every newspaper in the country began using large headlines for election day editions or illustrations and pictures to contextualize a crisis or celebration.

Hearst’s and Pulitzer’s newspapers eventually declined in circulation, but not before others had copied their methods.

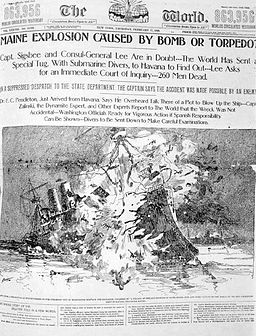

Oversized pictures, like this one in Joseph Pulitzer'sWorld, are characteristic of yellow journalism. (Feb. 17, 1898, public domain)

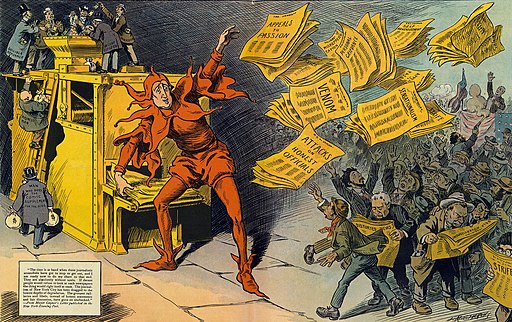

Illustration published in the New York Evening Post shows William Randolph Hearst as a jester tossing newspapers to a crowd of eager readers. It includes a note in the bottom left from the New York mayor which says, ” “The time is at hand when these journalistic scoundrels have got to stop or get out, and I am ready now to do my share to that end. They are absolutely without souls. If decent people would refuse to look at such newspapers the whole thing would right itself at once. The journalism of New York City has been dragged to the lowest depths of degradation. The grossest railleries and libels, instead of honest statements and fair discussion, have gone unchecked.” (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

The term ‘yellow journalism’ sourced to comic strip and editorials

Lore has suggested that the use of a comic strip illustrated by the World’s Richard Felton Outcault entitled “The Yellow Kid” (later poached by the Journal) and used to poke fun at industry, political, and society figures, was the source of the phrase “yellow journalism.”

Other sources point to a series of critical editorials by Ervin Wardman of the New York Press as coining the phrase after first attempting to stigmatize the practices as “new” and then “nude” journalism — “yellow” had the more sinister, negative connotation Wardman sought. Other editors began to use the term in their newspapers in New York, and it eventually spread to Chicago, San Francisco, and other cities by early 1897.

Illustration published in the New York Evening Post shows William Randolph Hearst as a jester tossing newspapers to a crowd of eager readers. It includes a note in the bottom left from the New York mayor which says, " "The time is at hand when these journalistic scoundrels have got to stop or get out, and I am ready now to do my share to that end. They are absolutely without souls. If decent people would refuse to look at such newspapers the whole thing would right itself at once. The journalism of New York City has been dragged to the lowest depths of degradation. The grossest railleries and libels, instead of honest statements and fair discussion, have gone unchecked." (Image via Library of Congress, public domain)

Supreme Court has set high bar for determining libel of public figures

Although modern journalistic standards are arguably as high as they have ever been, some Supreme Court decisions have allowed for criticism, especially of public figures.

In Near v. Minnesota (1931), the Supreme Court set a strong presumption against prior restraint of publication, and New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964) further set a high bar for public figures who thought that articles printed about them were libelous.

McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Commission (1995) also ruled that individuals can publish anonymous criticisms of political issues, and newspapers’ use of anonymous sources is largely governed by a code of journalistic ethics.

This article is originally published in 2009. Cleveland Ferguson III, J.D., D.H.L. is Senior Vice President and Chief Administrative Officer for the Jacksonville Transportation Authority