Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), author of the Declaration of Independence and third president of the United States, articulated and perpetuated the American ideals of liberty and freedom of speech, press and conscience.

Jefferson had law and political background

Jefferson was born in Goochland (now Albemarle) County, Virginia. His father, Peter Jefferson, died in 1757 when Thomas was only 14. Thomas inherited 5,000 acres and many slaves. He attended the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, Virginia, from 1760 to 1762, but left without a degree.

After studying law under prominent Virginia lawyer and judge George Wythe, Jefferson was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1767. In 1769 he began a six-year tenure in Virginia’s House of Burgesses.

Jefferson wrote Declaration of Independence in three days

In 1776, one year after he entered the Second Continental Congress, Jefferson, now 33, was one of five members selected to draft the Declaration of Independence. Following the lead of John Adams, the committee unanimously selected Jefferson to write the document, which he did over the course of three days. The Continental Congress then amended the Declaration and ratified it on July 4, 1776.

The Declaration of Independence is best known for articulating the natural rights philosophy that all people (“men”) are entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” and that they have the right to reject any government that does not secure such rights.

As he did throughout his life, Jefferson strongly believed that every American should have the right to prevent the government from infringing on the liberties of its citizens. Certain liberties, including those of religion, speech, press, assembly and petition, should be sacred to everyone.

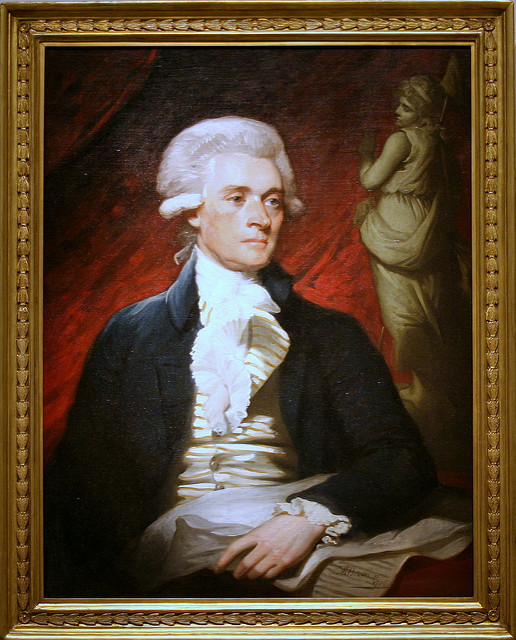

Thomas Jefferson wanted the new Constitution to be accompanied by a written “bill of rights” to guarantee personal liberties, such as freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom from standing armies, trial by jury, and habeas corpus. Jefferson’s correspondence with James Madison helped to convince Madison to introduce a bill of rights into the First Congress. After ratification by the requisite number of states, the first ten amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights, went into effect in 1791. (Image via Cliff on Flickr, CC BY 2.0, painted in 1786)

Jefferson wanted Bill of Rights for Constitution

Jefferson was serving as ambassador to France when the Constitutional Convention met in 1787 to replace the Articles of Confederation, but he remained well informed about events in America, largely because of his correspondence with his good friend James Madison.

Jefferson recognized that a stronger federal government would make the country more secure economically and militarily, but he feared that a strong central government might become too powerful, restricting citizens’ rights.

He therefore wanted the new Constitution to be accompanied by a written “bill of rights” to guarantee personal liberties, such as freedom of religion, freedom of the press, freedom from standing armies, trial by jury, and habeas corpus. Jefferson’s correspondence with James Madison helped to convince Madison to introduce a bill of rights into the First Congress. After ratification by the requisite number of states, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, known as the Bill of Rights, went into effect in 1791.

Jefferson drafted a precursor bill to the First Amendent

In Everson v. Board of Education (1947), Justice Hugo L. Black and some of his colleagues on the Supreme Court traced the origins of the First Amendment to a bill establishing religious freedom that Jefferson drafted and introduced in the Virginia General Assembly in 1779. The bill was not passed until 1786, when, through the efforts of James Madison, it was adopted as the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

The statute, which had three main sections, explained why compulsory religion requirements were wrong, stated that men were free to express their opinions on religion and choose how or if to worship without having their rights as citizens diminished, and explained how the right of freedom of religion was a natural right of mankind.

Justices on the Supreme Court traced the origins of the First Amendment to a bill establishing religious freedom that Jefferson drafted and introduced in the Virginia General Assembly in 1779. The bill was not passed until 1786, when, through the efforts of James Madison, it was adopted as the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. (Image via Independence National Historical Park on Wikimedia Commons, public domain, painted by Charles Wilson Peale in 1791)

Jefferson was a defender of freedom of conscience

Meanwhile, Jefferson’s own religious views appear to have been fairly unorthodox (for example, he attempted to edit references to miracles out of the Bible), and he was a strong defender of freedom of conscience.

During his presidency, Jefferson wrote a much-quoted letter to Baptists in Danbury, Connecticut, arguing that the First Amendment had created a wall of separation between church and state.

Jefferson opposed punishing speech through Sedition Act

Jefferson demonstrated his strong support for the First Amendment during the presidency of John Adams, a member of the Federalist Party. Jefferson belonged to the rival party, known variously as the Republican Party, Democratic-Republican Party, or Jeffersonian-Republican Party.

In 1798 the Federalist-dominated Congress passed the Alien Act, which allowed the president to deport any noncitizens he considered to be a threat to national security. That same year, Congress also passed the Sedition Act, which allowed the imposition of fines or imprisonment for anyone convicted of publishing false or malicious statements against Congress, the president, or any other part of the government.

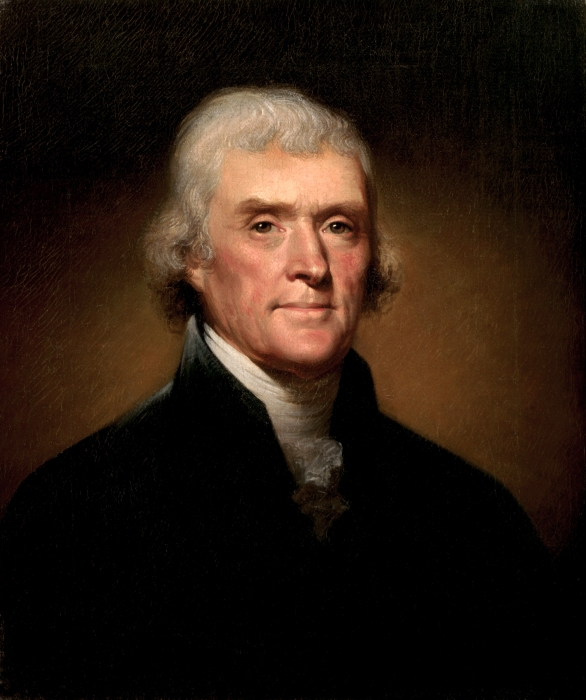

Thomas Jefferson thought the Alien and Sedition Acts to be clear violations of the freedoms of speech and the press guaranteed in the First Amendment.(Image via the New York Historical Society on Wikimedia Commons, public domain, painted by Rembrandt Peale in 1805)

Jefferson thought the Alien and Sedition Acts to be clear violations of the freedoms of speech and the press guaranteed in the First Amendment. In his mind, the acts were created simply to undermine his political party.

In response, he and Madison anonymously wrote the Virginia and Kentucky Resolutions of 1798, strongly suggesting that the federal government was overstepping the boundaries set forth not only in the First Amendment but also in the 10th Amendment, which reserved certain powers to the states.

In part because of these arguments, Jefferson won the presidential election of 1800 (resolved in 1801) and became the third chief executive of the United States. As president, Jefferson pardoned all those persons who had been convicted under the Sedition Act.

Before ascending to the presidency, Jefferson served as governor of Virginia, from 1779 to 1781, and secretary of state under President George Washington, from 1789 to 1793. As secretary of state, he often feuded with Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury. Jefferson, who preferred to use the pen as his primary means of attack, was quite sensitive to criticism.

In 1796, Jefferson lost the presidential election to Adams by three electoral votes, an outcome that under the Constitution earned him the vice presidency. In the election of 1800, Jefferson tied in electoral votes with fellow Democratic-Republican Aaron Burr, thereby forcing the House of Representatives to decide the outcome of the election. Hamilton disliked both men, but he supported Jefferson as the lesser of the two evils. In the end, Burr became Jefferson’s vice president.

After he left the presidency, Jefferson returned to his Virginia home, Monticello (pictured here), to pursue his numerous intellectual passions. On July 4, 1826, 50 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson died at Monticello. (Image via Martin Falbisoner on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 3.0)

As president, Jefferson tried to keep a weak national government

During his two terms in office, Jefferson sought to stay true to his principles of a weak national government by cutting the federal budget and taxes while still reducing the national debt. However, the most notable events of Jefferson’s presidency may seem to be at odds with these values.

They included:

- The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 in which Jefferson, in a constitutionally questionable act, approved the purchase before Congress authorized payment;

- The Jefferson-supported Embargo Act of 1807, which effectively prohibited all U.S. trade with other nations; and

- The Lewis and Clark expedition, which made many scientific discoveries while exploring the Louisiana Territory, which the nation had just purchased.

Critics charged that Jefferson exceeded the powers granted to him in the Constitution by engaging in these activities.

Jefferson dies on July 4, 1826 — 50 years after Declaration

After he left the presidency, Jefferson returned to his Virginia home, Monticello, to pursue his numerous intellectual passions. On July 4, 1826, 50 years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson died at Monticello. His former adversary and friend John Adams died the same day. After his death, Jefferson’s possessions were sold at auction at Monticello to cover his many debts.

At his request, Jefferson’s proudest accomplishments were listed on his gravestone: author of the Declaration of Independence, author of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, and father of the University of Virginia. Each was tied to his conception of freedom. The most lasting legacies of this complex man are the contributions he made to articulating American ideals and leading the nation during its early years.

This article was originally published in 2009. Carol Walker is an adjunct professor at George Mason University where she teaches about the First Amendment in courses on civil liberties, civil rights, and the Constitution. She holds a Ph.D. in Political Science with concentrations in American Government, Public Law, and Research Methods from Georgia State University.