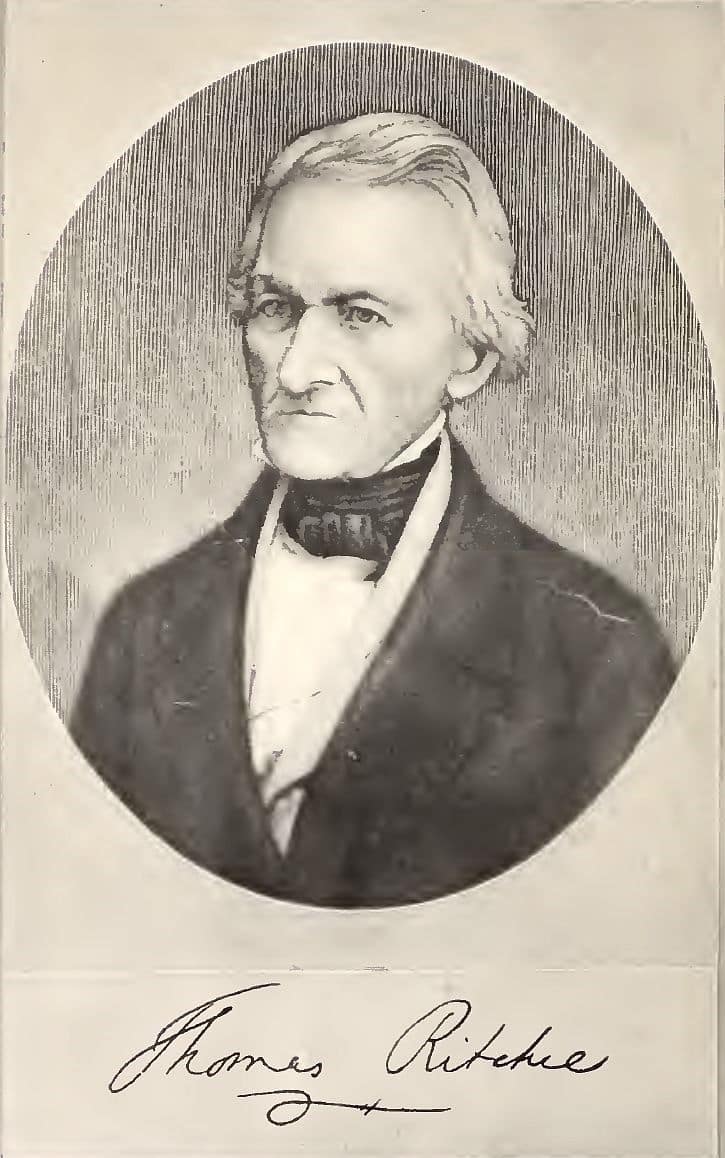

Thomas Ritchie was the editor and co-publisher of the Washington Daily Union, which was the official newspaper of the administration of President James K. Polk. He was also the official printer for both houses of Congress, a privileged position that gave him access to the floors of the Senate and the House.

On Feb. 13, 1847, during the Mexican War, the Senate voted to withdraw Ritchie’s floor privilege after a Union editorial letter accused a group of senators of aiding the Mexican cause by opposing war measures favored by President Polk. Administration allies denounced Ritchie’s expulsion as an attack on the freedom of the press.

Polk, Ritchie and the Daily Union

The background of the Ritchie affair began in March 1845. As he prepared to take office, Polk, a Democrat, wanted to ensure that an editor of unquestionable loyalty headed the party’s newspaper in Washington. Polk did not trust Francis P. Blair, the reigning editor of the Washington Globe, which was the top party organ during the presidencies of Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren.

Polk turned to Thomas Ritchie, the longtime editor of the influential Democratic newspaper the Richmond Enquirer, to replace Blair as the party’s principal editor in Washington. Polk and Ritchie wanted to replace the Globe as well. Ritchie and co-publisher John P. Heiss purchased the Globe, which they renamed the Daily Union.

While partisan newspapers and presidential administration newspapers had been the norm in the United States since the early decades of the Republic, the practice reached its apogee with the Union.

Under Polk’s supervision, Ritchie made no pretense of presenting the Union as anything but an administration mouthpiece. He always praised administration policies and the president, who often edited editorials and articles. Of course, the Union was merciless in its attacks on the opposition Whigs, which was expected. However, it also expended substantial ink criticizing congressional Democrats who opposed administration legislation.

Such attacks were problematic during the crisis-filled years of Polk’s presidency. A more diplomatic approach might have worked better with fellow Democrats as Polk pursued the annexation of the Oregon Territory and war with Mexico, issues that inflamed the growing sectional divide between North and South over the expansion of slavery. It was the Mexican War that set the stage for the confrontation between Ritchie and the Senate.

The Mexican War, John Calhoun and the Balance of Power Party

Controversial and divisive from the start, the war only grew more so as the United States failed to win a quick victory despite success on the battlefield. As the war lengthened, Polk’s relations with an increasingly divided Congress became tense. Most Democrats and Whigs agreed that the United States should acquire California and secure the Texas border on the Rio Grande. However, the question of taking land south of the Rio Grande opened fierce debate.

During this combative legislative atmosphere in early 1847, the Polk administration sought to reinforce U.S. forces in Mexico by having Congress authorize the raising of 10 new regiments for the Army. The “Ten Regiments Bill” quickly passed in the House and seemed to be on track in the Senate when a coalition of the entire senatorial Whig membership and a small group of dissenting southern Democrats derailed the legislation. Led by South Carolina’s John C. Calhoun, the Democratic faction consisted of Calhoun and three other senators: Andrew Butler of South Carolina and Floridians James D. Westcott Jr. and David Levy Yulee.

A Polk senatorial loyalist who opposed the faction, dubbed them the “balance of power party,” as they often held the balance of power in the Senate by sometimes siding with the Whigs on crucial votes.

Outraged by his own party’s failure to pass the Ten Regiments Bill, Polk had Ritchie aim his editorial pen against the balance of power Democrats. The Union said those responsible for the bill’s defeat would be held to account. On Feb. 9, Calhoun rose in the Senate to oppose occupying Mexican territory south of the Rio Grande. That evening, the Union published a letter titled “Another Mexican Victory,” signed by “Vindicator,” who proclaimed the defeat of the Ten Regiments Bill a victory for Mexico won by Mexico’s allies in the Senate.

Debating Ritchie’s Expulsion

On Feb. 10, Sen. Yulee offered a resolution in response to “Vindicator.” The resolution accused the editors of the Union of libeling the Senate and called for ending their privilege of access to the Senate floor. While the resolution did not name Ritchie, there was no question that the “editors” referred to him as the main editor of the Union.

The resolution sparked intense debate in the Senate and in newspapers across the country. Yulee and the other balance of power senators argued that even though Calhoun was not mentioned in the editorial, the piece was clearly aimed against him and was nothing less than an accusation of treason against the South Carolinian whose honor as a member of the Senate the body was called to defend. They blamed Ritchie for publishing the editorial, but their real target was President Polk, whom they accused of being the author behind “Vindicator.”

Ritchie’s Democratic defenders in the Senate said the resolution was an attack on the freedom of the press and an effort by Calhoun and his allies to promote Calhoun’s presidential aspirations for 1848. Raising the specter of the Alien and Sedition Acts, they protested that expelling Ritchie was an action akin to the Federalists’ effort to quash editorial opposition during the Quasi-War with France.

The Whigs might hate the Union as the organ of the Polk administration, but they had no right to punish the paper’s editor for exercising his constitutional right to publish legitimate political speech, even though their politics as the political opposition deemed that speech offensive. As for the balance of power Democrats, they were doing the bidding of their leader, Calhoun, in support of his political agenda.

The balance of power senators, led in the Senate debate by Sen. Westcott of Florida, fired back that far from being an attack on the freedom of the press, Ritchie’s expulsion was a straightforward question of honor and senatorial etiquette. As the official printer of the Senate’s proceedings and documents, Ritchie had been invited to enjoy the privilege of access to the Senate floor. However, like a houseguest who insulted the hosts, Ritchie had insulted Sen. Calhoun, a member of the Senate family. As Ritchie’s hosts, senators had the right and duty to expel Ritchie from their home to maintain honor and decorum. When the Senate voted on the expulsion resolution, Whigs and their Democratic partners won 27 to 21, with the balance of power Democrats providing the deciding margin.

Ritchie was expelled on Feb. 13, 1847. However, far from being a liability, the expulsion made him a martyr to the cause of freedom of the press. He lost access to the Senate floor but not to the editorial page of the Union, which proclaimed him the victim of Calhoun’s insatiable drive for the presidency powered by his clique of Democratic turncoats. The Union compared the Senate to England’s notorious Star Chamber that convicted individuals without allowing them due process or a fair trial.

Democratic newspapers championed Ritchie as a defender of the Fourth Estate victimized by aristocratic Whigs. The expulsion also proved to be a temporary boon to President Polk, whose Ten Regiment Bill the Senate reconsidered and passed in the wake of the expulsion vote.

The Ritchie affair subsided, and the war continued for another year. As the conflict ended in early 1848, the Senate voted to reinstate Ritchie’s floor privileges. By that time, however, the glow that surrounded Ritchie as a free press hero had long worn off. The growing wartime divide between North and South over the expansion of slavery only intensified in peacetime. Ritchie lost his monopoly on government printing. And support for official administration party organs in Washington weakened in the face of increased competition from an expanding popular press. In addition, national newspapers used the new telegraphic technology to receive daily news from their own reporters in the capital without having to rely on administrative organs such as the Union. Ritchie retired in 1851. He died in 1854 after almost 50 years in journalism.

Although the Ritchie affair was short-lived, it raised significant issues affecting freedom of the press, including free speech during wartime and congressional pressure on political reporting. In addition, Ritchie’s dual capacity as editor and administrative spokesperson made him vulnerable to attacks that his editorials were presidential hit pieces aimed at silencing political opponents under the cover of the First Amendment. Even in an age of a rabidly partisan press, Ritchie’s cheerleading for Polk was extreme. His embrace of the Polk administration stands as a forgotten forerunner of modern hyper-partisan media coverage of presidential administrations.

Boyd Murphree is the political papers archivist at the University of Florida.