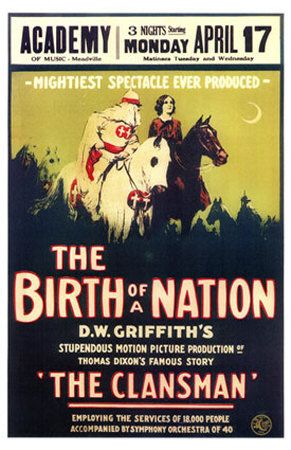

“The Birth of a Nation,” perhaps one of the most controversial movies in U.S. history, premiered as “The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan” in 1915 to be met with both rousing approval and indignant condemnation.

Attempts to block the film were common, but resistance to such efforts during the early part of the 20th century were not brought under the First Amendment. In fact, one of the first significant free speech cases did not appear until four years after the premiere—Schenck v. United States (1919). And it was not until the 1931 case of Near v. Minnesota that the Supreme Court considered the prior restraint concept in its First Amendment jurisprudence.

Film sparked the birth of the Second Ku Klux Klan

The film by producer and director D. W. Griffith was based on one volume of a racist trilogy written by former North Carolina Baptist minister Thomas Dixon Jr. 10 years earlier. Depicting the Ku Klux Klan as a group of heroes “saving” the South from blacks and the “horrors” of Reconstruction,” the book, together with the film, sparked the birth of the so-called Second Klan. After the book’s and the movie-playbill’s portrayal of a hooded Klansman riding a hooded horse, with his left hand holding the reins of the horse and his right hand holding a burning cross above his head, the Klan, the movie, and cross burning became synonymous.

Censorship efforts blocked

Efforts to censor “Birth of a Nation“ were in large part blocked using technicalities or some other existing substantive law. For example, in Wallace v. MacDonough Theater Co. (Cal. App. 1917), the plaintiffs failed to show any possibility of specific harm or that they had standing to complain of a public nuisance.

In Epoch Producing Corp. v. Schuettler (Ill. 1917), the attempt to censor was declared void by the trial court on the ground—not raised on appeal—that the obscenity ordinance was void for vagueness. Somewhat of an exception was Bainbridge v. Minneapolis (Minn. 1915), which involved a theater that violated the city’s censorship order. The theater was, however, denied relief for the post-showing revocation of its license because a revocation was deemed to be within the mayor’s discretion.

President Wilson’s approval of ‘Birth of a Nation’

President Woodrow Wilson, a southerner who had long been friends with Thomas Dixon and who had reintroduced Jim Crow segregation in federal jobs in Washington D.C., hosted a preview of the film at the White House. He was proud to see excerpts from his “History of the American People,” critiquing Black rule during congressional reconstruction and praising the Ku Klux Klan, emblazoned across the screen. Wilson contacted D.W. Griffith to praise the work, which, however, continued to evoke protests in some cities.

Not only were attempts to censor the film generally unsuccessful, but it won some acclaim within the film industry. The film was included in the National Film Registry in 1993 and voted one of the “Top 100 American Films” in 1998 by the American Film Institute. Presumably, it won the awards for its cinematography rather than for its racist message.

This article was published in 2009. Clyde E. Willis (1942-2017) worked an attorney for 25 years before starting a second career as a professor. He taught political science for 18 years at Middle Tennessee State University. He wrote the Student’s Guide to Landmark Congressional Laws on the First Amendment.