One of the controversial manifestations of America’s religious heritage has been efforts to display the Ten Commandments in various public venues, including in public schools, in courthouses and in public outdoor spaces.

Legal challenges have been brought against those efforts on the basis that they violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment, which reads, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion" — the so-called separation of church and state clause.

The issue of governmental sponsorship of public display of the Ten Commandments first came before the U.S. Supreme Court in Stone v. Graham (1980).

A Kentucky statute mandated that the Ten Commandments be posted on the wall of each public school classroom in the state. The displays were to be paid for by private funds, and an inscription below each was to read: “[T]he secular application of the Ten Commandments is clearly seen in its adoption as the fundamental legal code of Western Civilization and the Common Law of the United States.”

Court: Kentucky law requiring Ten Commandments in school classrooms violates establishment clause

In a per curiam (unsigned) opinion, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the displays violated the establishment clause. The Court relied upon the first part of its three-part Lemon test, which stated, “First, the statute must have a secular legislative purpose; second, its principal or primary effect must be one that neither advances nor inhibits religion. . . ; finally, the statute must not foster an excessive government entanglement with religion” (Lemon v. Kurtzman [1971]).

Kentucky’s avowed secular purpose notwithstanding, the Court said the statute violated the first prong of the test because “(t)he pre-eminent purpose for posting the Ten Commandments on schoolroom walls is plainly religious in nature.”

Ten Commandments also instruct about religious duties

The Court went on to point out that the Ten Commandments are “undeniably a sacred text in the Jewish and Christian faiths” and “do not confine themselves to arguably secular matters, such as honoring one’s parents, killing or murder, adultery, stealing, false witness, and covetousness. Rather, the first part of the Commandments concerns the religious duties of believers: worshiping the Lord God alone, avoiding idolatry, not using the Lord’s name in vain, and observing the Sabbath Day.”

Among the four dissenters, then Associate Justice William H. Rehnquist agreed with the trial court finding that the Decalogue’s (Ten Commandments) posting did fulfill a secular purpose, as Kentucky claimed.

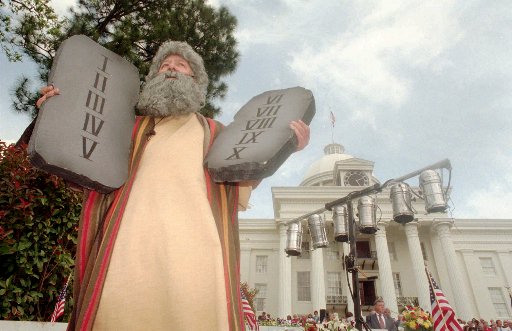

Tony Barkley, dressed as Moses, takes part in a dramatic presentation of the Ten Commandments on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery on April 12, 1997, during the “Save the Commandments Rally.” The rally was held in support of Judge Roy Moore’s right to display the Ten Commandments in his Etowah County courtroom. Moore later displayed a Ten Commandments monument in the Alabama Judicial Building. The 11th Circuit Court required him to remove the monument. (AP Photo/Kevin Glackmeyer)

Circuit Court forced Ten Commandments to be removed from Alabama capitol

In 2001, shortly after being elected to the position of chief justice of the Alabama State Supreme Court, Roy Moore had installed in the lobby of the Judicial Building a 5,280-pound monument of the Ten Commandments, commissioned at his personal expense. Moore placed the Commandments in the courthouse without consulting his fellow justices.

Shortly thereafter, a suit was brought against the action by the American Civil Liberties Union and Americans United for Separation of Church and State. A federal district court judge ruled against the chief justice, requiring him to remove the monument. When he refused to comply, a three-judge panel of the 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ordered the lower court judge to proceed with enforcement of the ruling in Glassroth v. Moore (11th Cir. 2003).

The U.S. Supreme Court subsequently denied Moore’s appeal on Nov. 3, 2003, and just 10 days later a judicial ethics panel in Alabama removed him from his seat on the state court.

Veterans and supporters watch as Paul Worthington, commander of the local American Legion post, hangs a copy of the Ten Commandments the McCreary County courthouse in Whitley City, Ky., on Oct. 10, 2000. The Supreme Court struck down Ten Commandments displays in courthouses in 2005, holding that two exhibits in Kentucky crossed the line between separation of church and state because they promoted a religious message. (AP Photo/Wade Payne)

Supreme Court uses Lemon test to decide Ten Commandments in Ky. courthouse case

Notwithstanding the earlier rulings against former chief justice Roy Moore, two counties in Kentucky posted large and readily visible copies of the Ten Commandments in their courthouses and were promptly sued by the American Civil Liberties Union. The counties then adopted almost identical resolutions that called for more extensive exhibits that would show that the Commandments were Kentucky’s “precedent legal code.” The new displays around the Decalogue featured eight smaller historical documents, including selected passages from the Declaration of Independence. The sole common element of each passage was a religious reference.

After the district court ruled against the displays, they were revised once more, without legislative sanction, to include nine framed documents of equal size, one of which was the Star-Spangled Banner, accompanied by statements about their historical and legal significance.

On June 27, 2005, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union against the displays. Writing for the majority, Justice David H. Souter found that the Lemon test was applicable and dispositive.

The counties claimed they had a secular purpose. While Souter acknowledged the deference usually accorded to a legislature’s stated reasoning for a statute, he said, “Lemon requires the secular purpose to be genuine, not a sham, and not merely secondary to a religious objective.”

Justice Antonin Scalia, reflecting the sentiments of the three other dissenters, took issue with the majority’s claim that government must remain neutral among religions. He challenged the assertion that public-square religion must be nondenominational: “If religion in the public forum had to be entirely non-denominational, there could be no religion in the public forum at all,” he claimed.

The state of Texas displayed a Ten Commandments monument on the capitol grounds as one of 39 monuments and historical markers spread over 22 acres that were meant to reflect the heritage of the Lone Star State. The monument in question had been standing for 40 years without challenge, apparently little noticed, and had been presented to the state by the Fraternal Order of Eagles of Texas, a private organization. The Court upheld the display. Visitor Darrell E. Way walks past the Texas stone bearing the Ten Commandments in Austin in 2002.. (AP Photo/Harry Cabluck,)

Texas display of Ten Commandments among 39 monuments upheld by Court

A companion case, Van Orden v. Perry (2005), also decided that day with a 5-4 ruling, presented a different set of facts that led to a different outcome.

Here, the state of Texas displayed a Ten Commandments monument on the capitol grounds as one of 39 monuments and historical markers spread over 22 acres that were meant to reflect the heritage of the Lone Star State.

The monument in question had been standing for 40 years without challenge, apparently little noticed, and had been presented to the state by the Fraternal Order of Eagles of Texas, a private organization.

Chief Justice Rehnquist, writing for the majority, which ruled in favor of the state’s display, strongly emphasized the passive nature of the arrangement and observed that “While the Commandments are religious, they have an undeniable historical meaning.”

Only the vote of Justice Stephen G. Breyer distinguished the McCreary and Van Orden holdings. In switching positions on the latter case, Justice Breyer labeled the Texas display “a borderline case” and ultimately determined that Texas had used the Commandments “as part of a display that communicates not simply a religious message, but a secular message as well.” He concluded that the monument’s physical setting and the circumstances surrounding its display suggested that the state intended for the “nonreligious aspects of the tablets’ message to predominate.”

Court: Utah's monument selection in parks is government speech

In 2009, the Court ruled in Pleasant Grove v. Summum that Utah city officials could refuse to place a monument from the religion of Summum in a public park even though they had a Ten Commandments monument already in their public park. The Court reasoned that monuments in a public park are a form of government speech immune from a free-speech challenge. It remains to be seen exactly how the government speech doctrine interacts with the establishment clause.

Louisiana law requires Ten Commandments in classrooms by 2025

Although these cases would appear to be fairly conclusive about rejecting displays of the Ten Commandments in school classrooms, the state of Louisiana adopted a law in 2024, requiring them to be displayed in all public school classrooms and in classrooms at state colleges and universities.

“If you want to respect the rule of law, you’ve got to start from the original lawgiver, which was Moses,” who got the commandments from God, said Gov. Jeff Landry who signed the law.

Supporters argued that the Ten Commandments, like the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution, were foundational documents and knowledge of which might help restore morality.

In Roake v. Brumley (2024), U.S. District Court Judge John W. deGravelles issued a preliminary injunction against the implementation of Louisiana's Ten Commandments law, arguing that Stone v. Graham remained a valid precedent, and finding that the classroom display of the Ten Commandments violated both the establishment and free exercise clauses of the First Amendment. He found that the Louisiana law was sectarian because it mandated a Protestant version of the Ten Commandments; it was discriminatory, because it honored the beliefs of some over others; and it was coercive because students were required to attend schools.

In arguing that the law also violated the free exercise clause, the judge pointed to the right of parents to oversee the religious education of their children without state interference or coercion. He also believed that the state could impart information about the significance of the Commandments through more narrowly tailored means than requiring a display of the Commandments in every school classroom.

Alabama Ten Commandments legislation furthers debate

In April 2025, Alabama’s House of Representatives followed Louisiana’s lead, adopting a bill mandating the display of the Ten Commandments in public schools. Similarly to the debate in Louisiana, Republican legislators in Alabama said that the Ten Commandments are an important foundation for understanding and respecting law.

“If you look around our nation, if you look around the world, we see so much of our Western civilization crumbling because we have forsaken the roots and foundations upon which we were built,” Rep. Ernie Yarbrough said.

Although the bill passed the House, it has been indefinitely postponed in the Senate.

Court view of Lemon test may affect new Ten Commandments cases

If a case challenging this law reaches the Supreme Court, and it reaffirms its decision in Stone v. Graham, it will almost surely declare the law to be unconstitutional, as it has done with most religious exercises (like prayer in public schools and Bible reading) in public schools. However, most of these decisions were based in large part on the Lemon Test, one prong of which required laws to have a primary effect that neither advances nor inhibits religion.

In 2002, however, the Court indicated it was abandoning the test when it decided in Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, that a public school coach had the right to pray on the football field after a game. Instead, it said it relied on “original meaning and history.”

In part because the Ten Commandments are part of the Judeo-Christian tradition, which was long taught, if not posted, in public schools, however, it is possible that the current Supreme Court would change its position. It might thus interpret the posting of the Ten Commandments, much as it has avoided ruling directly on the words “under God” in the pledge of allegiance and the words “In God We Trust” as a national motto, as acceptable forms of symbolic deism, from which children who disagreed with the Commandments could simply avert their eyes.

Since Protestants and Catholics number the commandments somewhat differently, it is possible that conflict could emerge as to which version of the commandments to post, which would be similar to earlier controversies over which version of the Bible to use when reading it in public schools.

This article was originally published in 2009 as written by Kenneth F. Mott, a retired professor of political science from Gettysburg College. It was last updated by John R. Vile, a professor of political science at Middle Tennessee State University, in June 2024.