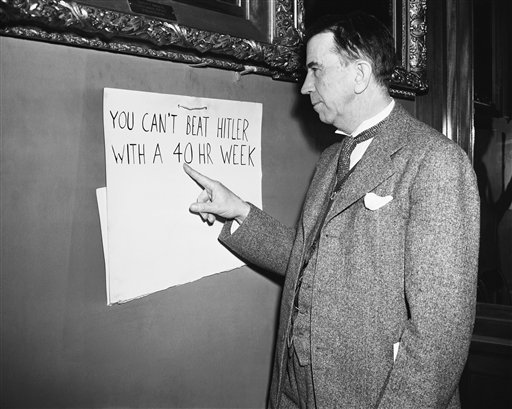

In 1940, Rep. Howard W. Smith, D-Va., responding to the escalation of armed conflict in Europe and what appeared to be a rise in communist and socialist movements in the United States, introduced legislation to restrict subversive activities.

Broadly written, the Smith Act forbade any attempts to “advocate, abet, advise, or teach” the violent destruction of the U.S. government. Meanwhile, the government apparently initiated prosecutions against many communists for their political beliefs, triggering First Amendment concerns.

Smith Act used to prosecute Socialist, Communist leaders

In 1941 the first prosecutions — leaders of the Socialist Workers Party in Minneapolis — were carried out under the Smith Act.

Working with local Teamster union leaders, the socialist leaders had agitated for the continued use of labor strikes and disruptions during World War II to advance their positions. The 23 defendants found guilty of violating the Smith Act received jail sentences.

Ironically, the Communist Party of the United States supported the government’s position in this case. Germany’s 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union solidified the U.S.-Soviet alliance and aligned communist interests more closely, at least temporarily, with U.S. foreign policy. However, as the cold war emerged, Communist Party leaders found themselves at the center of Smith Act prosecutions.

In 1948 the national executive leaders of the U.S. Communist Party were charged with violating the Smith Act. The government argued that the Communist Party was part of a conspiracy to advance a political ideology whose eventual goal was the destruction of the U.S. government.

Court upheld Smith Act against First Amendment challenge

The 11 convicted defendants appealed their cases to the Supreme Court, arguing that the Smith Act violated the First Amendment. The Court disagreed.

In Dennis v. United States (1951), the Court ruled that the act was constitutional, and, according to Chief Justice Frederick Moore Vinson, the law “may be applied where there is a ‘clear and present danger’ of the substantive evil which the legislature had the right to prevent.”

In 1957 the Court once again ruled in a case involving the prosecution of Communist Party leaders.

Court overturned Smith Act convictions in 1957

Yates v. United States (1957) turned primarily on the difference between abstract advocacy and advocacy that called for immediate action.

The convictions in Dennis and the charges in Yates were dependent on showing that a conspiracy was in place to overthrow the government. In its decision in Yates to reverse the convictions and send the case back to the lower courts with new instructions, the Court drew a distinction between political positions that advocated an abstract point (for example, the advocacy was not connected with any effort to overthrow the government) versus advocacy that involved immediate or future actions.

Writing for the majority, Justice John Marshall Harlan II signaled the Court’s intention to employ a balancing test when weighing free speech considerations rather than the clear and present danger standard. This approach allowed free speech protection of abstract doctrines. The Court also concluded that the “organizing” intent of the Smith Act was restricted to a group’s founders and not subsequent joiners. This ruling made future prosecutions under the “organizing” provisions of the act virtually untenable.

Court indicated mere Communist membership would not violate Smith Act

In Scales v. United States (1961) and Noto v. United States (1961), the Supreme Court reviewed the Smith Act’s membership provision, which made it a felony to be a member of an organization that advocated the overthrow of the United States.

In Scales, the Court considered whether, under the Smith Act, individuals could be prosecuted for being a member of the Communist Party. The Court upheld the conviction of Julius Scales by finding that his conviction was not predicated on mere membership in the party, but his active participation in the group, which negated a due process claim. Citing Dennis, the majority concluded in Scales that there also was no free speech violation. Advocacy with intent was not protected.

In Noto, the companion case to Scales, the Court unanimously reversed John Noto’s conviction, holding that there was not sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the Communist Party to which Noto belonged was engaged in advocating the overthrow of the government. The advocacy of abstraction was constitutionally protected.

Although the Smith Act is still part of the U.S. legal landscape, the Scales and Noto cases are the last significant prosecutions tied to the law.

This article was originally published in 2009. Alec Thomson is a professor of political science and history at Schoolcraft College in Livonia, Michigan. He is the editor of The Community College Enterprise, a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to publishing research on teaching and learning within the community college arena.