In Scales v. United States, 367 U.S. 203 (1961), the Supreme Court narrowly upheld the conviction of Junius Scales, a Communist Party member, under the membership clause of the Smith Act of 1940, which made it a crime to be a member of the Communist Party.

The Supreme Court’s record on the First Amendment and communism in the initial years of the Cold War had been mixed. With McCarthyism at its height, the Court deferred to Congress.

Supreme Court allowed conviction of Communist leaders based on ‘clear and present danger’

In the most crucial precedent, Dennis v. United States (1951), the Court interpreted the “clear and present danger” standard as permitting the conviction of Communist Party leaders based on their abstract desire to see an overthrow of the government at some unspecified point in the future (but without any overtly revolutionary acts).

However, following the disgrace of Senator Joe McCarthy, the Court became less deferential, throwing out 12 consecutive convictions of alleged communists. Crucially, most of these decisions did not rest on explicit First Amendment grounds, but rather overturned convictions on technical grounds and by reading the Smith Act narrowly.

Court upheld Junius Scales’ conviction, though narrowed interpretation of Smith Act

Writing for the 5-4 majority in Scales, Justice John Marshall Harlan II navigated between these potentially competing lines of precedent.

Continuing the Court’s post-McCarthy jurisprudence, Harlan continued to use an (arguably implausibly) narrow construction of the Smith Act. Basing his decision on the Court’s holding in Yates v. United States (1957), Harlan interpreted the Smith Act as permitting convictions under the membership clause only if (1) the individual was an “active and purposive” member of the Communist Party, who had (2) direct “knowledge of the organization’s illegal advocacy.”

The Court held that both elements had been satisfied by the state. Having read the statute and the evidence in this way, Harlan’s First Amendment analysis was perfunctory. Relying on Dennis, he argued that “little remains to be said” on the First Amendment issues, as the Court had already established that the membership clause was constitutional.

Dissent said that under First Amendment mere association could not be convicted

In dissent, Justice Hugo L. Black and William O. Douglas repeated the arguments that the constitutional analysis of Dennis was erroneous. Black, reasserting his familiar First Amendment absolutism, argued that the “balancing test” used by the Court in Smith permitted the upholding of virtually any restriction of speech despite the explicit text of the First Amendment.

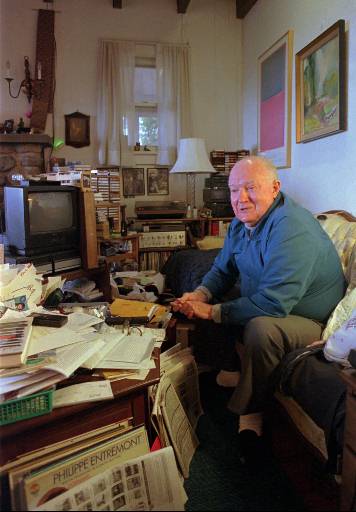

Scales had been a prominent target of U.S. government agents for his activities in organizing tobacco and mill workers in the South for the Communist Party. He is shown here in 1996. (AP Photo/Jim McKnight, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Douglas argued that under the First Amendment mere association could never be grounds for a conviction and that because a charge of conspiracy “rests not in intention alone, but in an agreement with one or more others to promote an unlawful project,” Scales’s actions could not be considered an illegal conspiracy.

Finally, Justice William J. Brennan Jr. held that the membership clause of the Smith Act had been superseded by section 4(f) of the Internal Security Act, and therefore Scales was immunized from prosecution by Congress.

Scales created middle ground for relevant First Amendment issues

In Scales, the Court staked out a middle ground on the relevant First Amendment issues, narrowing the scope of potential state action but permitting some convictions for membership in political parties alone under the First Amendment.

Junius Scales served 15 months of a six year sentence before President John F. Kennedy commuted his sentence on Christmas Eve 1962. He died in 2002.

This article was originally published in 2009. Scott Lemieux is a Lecturer in the Political Science Department at the University of Washington.