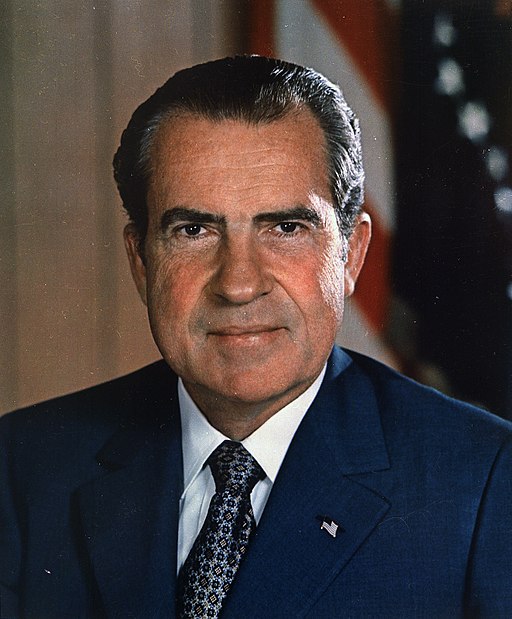

Richard Nixon (1913–1994), the 37th president of the United States, served from Jan. 20, 1969, until his resignation on Aug. 9, 1974 — a tumultuous period marked by ongoing civil rights upheavals, protests against the Vietnam War, and executive wrongdoing and investigations. For many observers, Richard Nixon’s conduct during this time typified executive abuse of power, even at times threatening the freedoms of speech, press, and political association.

Nixon, a World War II Navy veteran who was born in California, had a long political career that included service in both the U.S. House of Representatives (1947–1950) and U.S. Senate (1950–1953). He also served as President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s vice president (1953–1961). During his service in the House, Nixon helped to expose State Department official Alger Hiss as a Soviet spy. Playing off the fears generated by McCarthyism, he moved to the Senate by painting his opponents as “pink.”

Nixon argued a First Amendment case

Richard Nixon lost the presidential election of 1960 to Democrat John F. Kennedy, and he failed to win the governorship of California in 1962. He then resumed practicing law (he had graduated from Duke Law School) and contributed to First Amendment jurisprudence by arguing for the Hill family before the Supreme Court in Time, Inc. v. Hill (1967).

Although the Hill family had won damages in a lower court, the Supreme Court rejected the idea that a Life magazine article about the hostage ordeal endured by the family portrayed it in a “false light” for which it should be able to sue.

In 1968, Richard Nixon once again entered politics and won the presidential election. He served one and a half terms before resigning in the wake of the Watergate scandal.

As president, he is remembered positively for his many foreign policy accomplishments, including ending U.S. combat in the Vietnam War, opening diplomatic relations with China, and establishing détente with the Soviet Union.

Nixon and church services at the White House

Although Nixon (like Herbert Hoover) had been raised as a Quaker, as an adult he rarely attended Quaker services, he was generally uncomfortable worshipping in public, and as president he brought worship services to the White House. These services, which seemed to blend both public and private and church and state, were highly choreographed events, with limited invitations to attend chiefly extended to VIPS and primarily made with a view toward political advantage.

The services tended to insulate Nixon from much of the opposition that he faced for the continuing war in Vietnam and criticism over the Watergate break in and coverup. Pastors who attended were reluctant to direct criticism to Nixon on his home turf and were more inclined “to praise and flatter” him (Silliman 2024, 164). Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr observed that “It is wonderful what a simple White House invitation will do to dull the critical faculties” (Silliman 2024, 165).

As at his inaugurations where he had recruited five pastors from various denominations to pray, Nixon invited Roman Catholics, Jews, and others to speak and attend services at the White House. Nixon relied in part on the counsel of evangelist Billy Graham, who sought individuals who would stick to spiritual matters in their sermons rather than to political themes.

Nixon often signed Bibles of those who attended, much as President Donald Trump would later be criticized for doing when he signed covers of Bibles of Alabama tornado victims (Vile 2020, 492).

As Nixon was overwhelmed by fallout from the Watergate crisis, he asked Secretary of State Henry Kissinger to kneel in prayer with him in the Lincoln sitting room noting that “you are not a very orthodox Jew. And I am not an Orthodox Quaker. But we need to pray.” (Silliman 2024, 2)

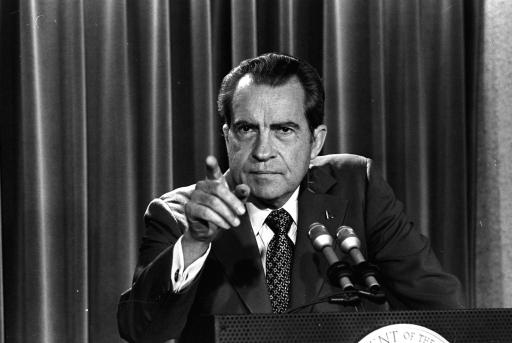

Nixon seemed to operate above the law in domestic policy

In the domestic policy arena, however, Nixon is reviled for his perceived and real excesses, some of which were tied to his attempts to maintain secrecy in matters related to foreign affairs.

Nixon’s administration seemed to operate above the law. Revelations about the use of both the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation to infiltrate and spy on social activist groups, ranging from civil rights organizations to consumer protection groups and especially the anti-war movement, threatened freedom of association and contributed to the perception of Nixon as Machiavellian.

The president’s “enemies lists” of civil rights and anti-war leaders, as well as liberal activists, politicians, journalists, and fund-raisers, enhanced his image as an officeholder who personalized his opposition and justified use of the power of his office to counteract their efforts.

Nixon’s administration tried to discredit the Pentagon Papers leaker

Nixon was also involved in a pivotal Supreme Court case centering on freedom of the press. RAND analyst Daniel Ellsberg, leaked to The New York Times a secret history of the Vietnam War (known as the Pentagon Papers) that contained admissions of lies and cover-ups about the conduct of the war.

The Nixon administration was aware that the secret documents addressed decisions made by Nixon’s predecessors, but nonetheless in June 1971, began a campaign to discredit Ellsberg.

Among other things, administration operatives broke into the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist in California to retrieve damaging information on Ellsberg.

The administration’s U.S. Department of Justice secured a restraining order barring newspapers from publishing the contents of the study, which was appealed.

In New York Times Co. v. United States (1971), the Supreme Court held that the government did not have the right to invoke prior restraint on the New York Times and the Washington Post for publishing excerpts of the Pentagon Papers.

The problems afflicting the Nixon administration extended to campaign practices as well. Irregularities, especially in fundraising in the 1968 presidential election, ultimately led to Congressional passage of the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA) in 1971.

Nixon’s re-election campaign led to the Watergate scandal

Nevertheless, the 1972 election was rife with corruption, which culminated in what came to be known as the Watergate scandal, but included earlier wrongdoing.

Two well-known efforts to subvert the political process were the creation and operation of the “plumbers” unit, a group dedicated to “plugging leaks” within the administration, and of the Committee to Re-Elect the President (CREEP), which engaged in “dirty tricks” to stymie the political and personal opposition to Richard Nixon and his administration. One such trick was the break-in by members of CREEP at the 1972 national headquarters of the Democratic Party in Washington’s Watergate Hotel; the burglars were seeking campaign intelligence.

Nixon resigned to avoid impeachment

During the hearings of the Senate Watergate Committee, a special committee convened to investigate the Watergate burglary and the surrounding scandals, the president lost yet another court decision in which the Supreme Court upheld a 1974 ruling in United States v. Nixon that the president had to surrender tapes of his personal conversations to the special prosecutor appointed to investigate administration activities.

These tapes contained the “smoking gun” that revealed Richard Nixon had orchestrated the Watergate cover-up. To avoid certain impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate, the president resigned from office.

Nixon on Nixon

In 1977, British journalist David Frost conducted a series of 12 interviews with Nixon, for which Nixon was paid. The interviews were broadcast in the United States in five parts, beginning on May 7, 1977.

The wide-ranging conversations included Nixon’s assertion that he was not trying to cover up crimes.

“My motive in everything I was saying or certainly thinking at the time was not to try to cover up a criminal action but … to be sure that as far as any slip-over — or should I say slop-over, I think, would be a better word — any slop-over in a way that would damage innocent people. … We weren’t going to allow people in the White House, people in the committee [his re-election committee] at the highest levels who were not involved to be smeared by the whole thing. In other words, we were trying to politically contain it.”

Nixon acknowledged in the interview that he had “let the American people down.”

Nixon told Frost, “It was so botched up. I made so many bad judgments. The worst ones, mistakes of the heart rather than the head, as I pointed out. But let me say a man in that … top job, he’s got to have a heart but his head must always rule his heart.”

The interviews inspired the 2004 play Frost/Nixon by Peter Morgan and the subsequent 2008 film.

This article was originally published in 2009 and was updated in November of 2023. Matthew M. Caverly is a lecturer at Middle Georgia State University. He teaches courses in American civics including an extensive section on the “1st Amendment Freedoms.” Caverly received his Ph. D. in political science from the University of Florida.