An intrusion on seclusion claim applies when someone intentionally intrudes, physically or through electronic surveillance, upon the solitude or seclusion of another. This form of invasion of privacy has implications for the First Amendment, particularly when members of the press are punished for their news-gathering activities. For example, a First Amendment clash may arise when members of the paparazzi are targeted for their invasive conduct.

Intrustion is different than trespass

Intrusion differs from trespass, which is a civil claim or a criminal charge for entering private property without the owner’s consent. In addition to unauthorized physical entry, eavesdropping, and wiretapping, an intrusion claim can be brought for lying or misrepresenting circumstances in order to obtain entry, or exceeding the consent given for entry.

Plaintiffs must prove a reasonable expectation of privacy

To pursue an intrusion on seclusion claim in most states, a plaintiff must establish several things.

- The defendant, without authorization, intentionally invaded the plaintiff’s private matters.

- The invasion is offensive to a reasonable person.

- The matter that the defendant intruded upon is a private one.

- The intrusion caused the plaintiff mental anguish or suffering.

The intrusion itself is actionable, regardless of whether any information is communicated to others.

More broadly, to prove intrusion claims plaintiffs must show that they had a reasonable expectation of privacy. Courts have found such an expectation in one’s home, as well as in public facilities such as locker rooms and bathrooms. Courts have also found a reasonable expectation of privacy in financial matters, telephone calls, and personal postal and electronic mail.

Such an expectation may also be based on privacy statutes, which may impose their own penalties. These statutes, which address the use of surveillance and bugging equipment, vary by state. But the general rule is that photographing or recording anything that occurs in, or can be easily seen from, public areas is not actionable; use of special equipment to see or hear activity in a private place or that an unaided person would not be able to see or hear is actionable.

Federal wiretapping laws apply to cell phones and e-mail as well as oral communication

The laws on eavesdropping and wiretapping of telephone and electronic communications are complicated and vary by state. Federal law generally prohibits interception of oral communications without consent, although major exceptions are applicable to business such as the “telephone extension” exception, which allows employers to monitor business phone calls “in the ordinary course of business.” If users have been informed of monitoring, continued use is considered consent.

The federal wiretapping law also applies to cell phones and e-mail. Most courts have held that the federal law applies only to e-mails while “in transit,” not when they are “stationary” (for example, stored on a hard drive), even if the storage is fleeting and temporary. But recently a federal appeals court held in United States v. Councilman (1st Cir. 2005) that e-mails are covered whether in transit or in storage.

As electronic communication continues to expand and fears of identity theft rise, intrusion claims will undoubtedly expand to cover these forms of communication. The same can be said of cell phones able to capture images; it is feared that their use in locker rooms and restrooms will raise privacy concerns. Whether and how state provisions apply to email and cell phones depends on how they have been written and interpreted.

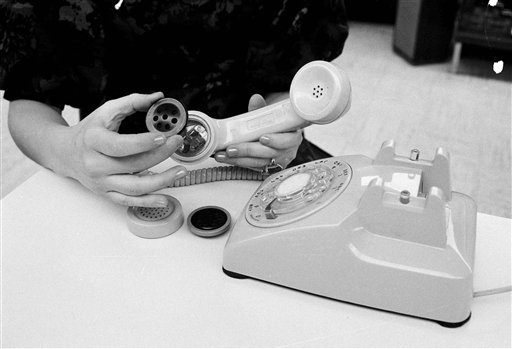

States differ in their privacy statutes that deal with electronic surveillance devices. In this 1973 photo, Ed Bray, 48 and Joe Paolella, 44, right, examine a wall plug device in their office in Chicago. The box-like device was used to locate listening devices. (AP Photo/Charles E. Knoblock, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

States have their own eavesdropping laws

In addition to the federal laws, every state but Vermont (where state courts have still set limits on the practice) has its own eavesdropping law. Most (39 states and the District of Columbia) require “one party consent” to record a conversation, and 11 states require all parties to consent.

A recent well-known example of such eavesdropping was the 1997 recording made by government worker Linda Tripp of her telephone conversation with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. In that conversation, Lewinsky disclosed her sexual liaison with President Bill Clinton. The telephone conversation, which was later released to Newsweek magazine, was taped in Maryland, one of the states in which both parties must consent to the taping.

Informed consent is the defense to intrustion claims

Consent is a defense to an intrusion claim. However, it must be informed consent and from someone with a legal right to give it. Consent is easiest to prove when in writing. Lying in order to receive consent renders the consent invalid. An action can still be found to be intrusion if it exceeds the scope of the consent granted.

Intrusion raises First Amendment concerns

Intrusion raises several First Amendment issues. For one thing, a defendant cannot defeat a private effort to sue for intrusion by raising a First Amendment right to free speech. If in fact privacy has been invaded, then the victim can sue and collect for damages. In addition, the government can enhance some privacy laws to protect against intrusion. Although such laws may limit the free speech ability of intruders to intercept and release information, these laws also facilitate and promote privacy and free communication among users, thereby promoting the type of communication that the First Amendment favors.

This article was originally published in 2009. Eric P. Robinson is an attorney and scholar focused on legal issues involving the media, including the internet and social media. He is currently Assistant Professor in the School of Journalism and Mass Communications at the University of South Carolina and is also “of counsel” to Fenno Law in Charleston/Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, which focuses on media and internet law.