Congress adopted the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993 to override the Supreme Court decision in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990) and provide greater protection under the First Amendment free exercise clause.

In City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), the Court struck down the provisions of the RFRA as they applied to the states. RFRA remains constitutional on the federal level.

Congress passed Religious Freedom Restoration Act after First Amendment free exercise case

In Smith, the Court upheld a decision by an Oregon state agency to deny unemployment benefits to two Native Americans who were dismissed from drug counseling jobs because they had tested positive for peyote, a hallucinogenic drug. Both men had ingested the drug in a Native American religious ceremony.

Justice Antonin Scalia, writing for the majority, ruled that “generally applicable religious-neutral criminal laws” do not violate the free exercise rights of individuals. Critics of the decision charged that the Court had effectively overturned a century of case law, including decisions in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) and Sherbert v. Verner (1963), which held that courts should use strict scrutiny to examine laws that restrict the religious acts of individuals.

RFRA said courts have to use strict scrutiny when examining laws relating to religious freedom

Congress responded with the RFRA to mandate that the courts use strict scrutiny when examining laws that substantially affect religious freedom.

In doing so, Congress relied upon its authority under the enforcement clause, section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, to protect the constitutional rights of individuals.

Court limited RFRA, cited separation of powers

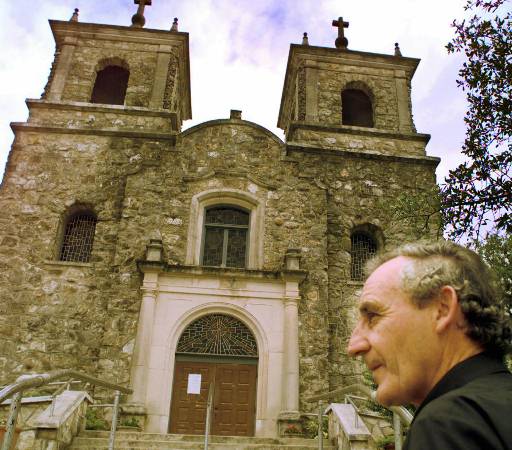

In Boerne, the courts examined a decision by the City of Boerne, Texas, to deny a Catholic church a permit to expand its building to accommodate its growing congregation. The church sued, contending that the decision violated its free exercise rights and relying upon the RFRA’s requirement of strict scrutiny to bolster its case. The Supreme Court ruled against the church and declared the RFRA unconstitutional.

Writing for the Court, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy asserted that in the case of the RFRA, Congress lacked authority under the Fourteenth Amendment, because in the hearings and debates on the act, it had failed to show that any violation of individual rights had occurred; the section 5 enforcement power only applies to an actual or real infringement of rights. The Court also ruled that the RFRA violated the principle of separation of powers and upset an important federal-state balance of powers by interfering with states’ traditional authority to regulate the health and safety of its citizens.

As a result of Boerne, a number of states adopted their own “mini-RFRAs” to address free exercise claims in their court systems.

Congress created a narrower religious liberty law

Moreover, in Gonzales v. O Centro Espirita Beneficente Uniao do Vegetal (2006) the Court ruled that the RFRA was valid as it applied to the federal government. The debate between Congress and the Supreme Court over the level of religious liberty protection remains ongoing.

After the Court’s decision in Boerne, Congress responded with a narrower religious liberty law, the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA). The Court rejected an establishment clause challenge to institutionalized persons aspect of RLUIPA in Cutter v. Wilkinson (2005).

Kristin Hughs, left, announces to supporters the Supreme Court’s decision on the Hobby Lobby case in Washington in 2014. The Supreme Court applied the RFRA to corporations and said they can hold religious objections that allow them to opt out of the new health law requirement that they cover contraceptives for women. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court used RFRA to uphold Hobby Lobby’s religious-based exemption to federal health care law

The most recent controversy regarding RFRA concerns its application to corporations.

In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby Stores, Inc. (2014), a sharply divided U.S. Supreme Court determined that closely held corporations were persons within the meaning of RFRA and could assert a religious-based exemption to the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act to having to provide contraceptive coverage for employees. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dissented, writing that “[although the court attempts to cabin its language to closely held corporations, its logic extends to corporations of any size, public, or private.”

Later, the Court in Zubik v. Burwell (2016) vacated judgments from four federal courts of appeals – the Third, Fifth, Tenth, and D.C. Circuits – that had found that federal regulations requiring employers to provide contraception coverage to their employees did not violate non-profit religious organization-employers’ religious liberty rights under the RFRA.

This article first was published in 2009 and has been updated. The primary contributor was David Schultz, a professor at Hamline University. It has been updated by other First Amendment Encyclopedia contributors.