The activities of political parties enjoy significant protection under the First Amendment. For instance, parties generally are able to assert a freedom of association claim, arguing that they, not the government, have the right to decide who may join the organization or be excluded and how they conduct their internal affairs. It is not always clear, however, who, under the law, is the “political party” and who can assert First Amendment rights.

Who makes up the political party for First Amendment purposes?

For example, is the political party its leadership, primary voters, or potential primary voters? If the former, then can they place limits on who may join or participate in the party? If so, then they may be able to invoke the First Amendment on behalf of the party’s right to exclude individuals. If the party is not the leadership but the voters, then they may be able to invoke the First Amendment to demand admittance.

Political parties are public associations and subject to regulation

One of the first questions surrounding the regulation of political parties is whether a party is a public or a private association. In a series of decisions known as the “White Primary Cases” from Texas in the 1920s to the 1940s, the Supreme Court vacillated between ruling that the Democratic Party primaries in that state were private—and therefore the party could exclude African Americans from participating—or subject to state and congressional regulation such that discrimination could be prohibited. Eventually in United States v. Classic (1941) and Smith v. Allwright (1944), the Court ruled that the party primaries were subject to regulation and that African Americans could not be barred from participating.

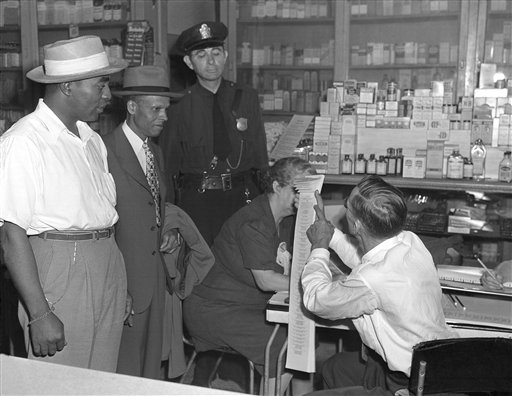

One of the first questions surrounding the regulation of political parties is whether a party is a public or a private association. In a series of decisions known as the “White Primary Cases” from Texas in the 1920s to the 1940s, the Supreme Court vacillated between ruling that the Democratic Party primaries in that state were private—and therefore the party could exclude African Americans from participating—or subject to state and congressional regulation such that discrimination could be prohibited. Eventually in United States v. Classic (1941) and Smith v. Allwright (1944), the Court ruled that the party primaries were subject to regulation and that African Americans could not be barred from participating. In this photo, W. R. Owens, right, election official tells two African Americans who tried in vain to vote in Atlanta’s city Democratic white primary on Sept. 5, 1945, that the primary is for white persons only and points to the top of the ballot which so states. They are Lewis K. McGuire, left, World War II veteran, and S. M. Lewis, a physician. Beside them stands policeman Roy Wall. (AP Photo/McD, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Although these cases were decided under Article 1, section 4, of the Constitution and the Fifteenth Amendment, they opened up political parties to government regulation. These decisions forced new questions upon the Court: If the government could tell a political party that it could not discriminate against individuals on the basis of race, could it not also tell a party whom it must admit as a member? For example, could it require the Republican or Democratic Party to admit a member of another party, or a political independent, to participate in a primary or convention? Could it bar a party from letting nonparty-members participate in its activities?

Political parties have free association rights, but it is not clear who can assert them

In Tashjian v. Republican Party of Connecticut (1986), the Court invalidated a state’s closed primary law that prevented one party from inviting independent voters from participating in its primaries. Moreover, in Eu v. San Francisco County Democratic Central Committee (1989) the First Amendment was used to strike down a state law banning political parties from making political endorsements. In addition, in California Democratic Party v. Jones (2000) the Court voided on First Amendment grounds a state law that turned the California primaries into “open primaries” whereby anyone of any affiliation could vote in a party primary.

The Court in these three cases seemed to state that the right to free association applied to political parties and that they have the right to decide with whom to affiliate, so that the government can not prescribe whom a political organization decides to admit in a primary or endorse.

Yet in Clingman v. Beaver (2005) the Court upheld an Oklahoma semi-closed primary system that restricted who could vote in a primary. The Supreme Court stated here that the law was not so burdensome to the First Amendment rights of parties as to even require strict scrutiny. As a result of these decisions, it appears that political parties have free association rights, but it is not always clear who can assert them—the party members or the leaders.

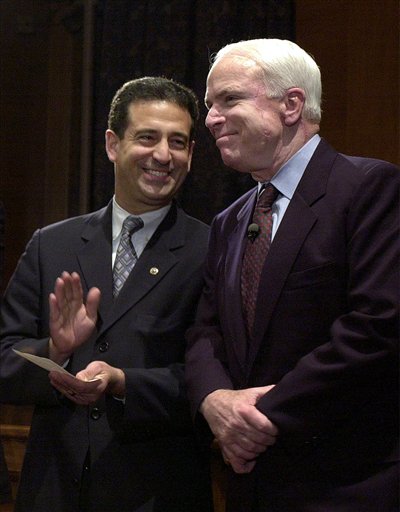

Another line of cases addressing the First Amendment rights of political parties has dealt with campaign financing. In McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003),the Supreme Court upheld a portion of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (McCain-Feingold Act) that barred so-called soft money contributions to political parties. In this March 20, 2002, photo Sen. Russ Feingold, D-Wis., left, and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., the two senators who sponsored the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act, smile during a rally on Capitol Hill in Washington. (AP Photo/Dennis Cook, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Party campaign financing is another First Amendment issue

Another line of cases addressing the First Amendment rights of political parties has dealt with campaign financing. In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Supreme Court upheld the 1974 amendments to the Federal Election Campaign Act, which, among other things, created a system for the public financing for presidential elections, imposed contribution limits to political parties, and made it illegal for parties to coordinate or plan their expenditures, or spending, with candidates for public office. In Buckley the Court rejected First Amendment challenges to contribution limits and upheld a law mandating that a political party had to receive at least 5 percent of the popular vote in a presidential election to be eligible for public funding. Minor political parties had contended that the 5 percent threshold violated their First Amendment rights.

Eventually, in Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee v. Federal Election Commission (1996), the Court used the First Amendment to strike down expenditure limits made by parties that were not coordinated with a candidate, but subsequently in Federal Election Commission v. Colorado Republican Federal Campaign Committee (2001), it upheld a ban on coordinated contributions. Finally, in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003),the Supreme Court upheld a portion of the Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (McCain-Feingold Act) that barred so-called soft money contributions to political parties.

Minor or third parties, such as the Green Party or Libertarian Party, have been subject to specific regulations, often requirements for ballot access. The Court has ruled that these special rules may violate the First Amendment rights of these parties. In some cases, independent and third-party candidates are required to file a requisite number of signatures in order to appear on the ballot. If that minimum threshold is too high, the Court may invalidate it as a First Amendment violation. In this Sept. 21, 2012 photo, Libertarian Party presidential nominee Gary Johnson, right, greets students at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota. (AP Photo/Jim Mone, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Ballot access rules may violate the First Amendment

In addition to the rules affecting the general rights of parties, minor or third parties have been subject to specific regulations, often requirements for ballot access. The Court has ruled that these special rules may violate the First Amendment rights of these parties.

In some cases, independent and third-party candidates are required to file a requisite number of signatures in order to appear on the ballot. If that minimum threshold is too high, the Court may invalidate it as a first Amendment violation. For example, in Illinois State Board of Elections v. Socialist Workers Party (1979) the Court ruled that a state law requiring a minor party to obtain more than 25,000 signatures to appear on the ballot violated its First Amendment rights.

On the other hand, the Court ruled a few years later in Norman v. Reed (1992) that requiring candidates for suburban district offices to obtain 25,000 signatures from the suburbs of Chicago to appear on the ballot was not a First Amendment violation.

In Munro v. Socialist Workers Party (1986), the Court upheld a requirement that a party secure at least 1 percent of the vote in a primary for its name to appear on a general election ballot. The Court noted that while the 1 percent requirement did impinge upon the First Amendment rights of the party, these rights were not absolute, and it was not burdensome to require the party to demonstrate some minimum level of support to appear on the ballot.

Finally, in Timmons v. Twin Cities Area New Party (1997) the Court upheld against a First Amendment challenge a Minnesota law barring a candidate from one political party from appearing on the ballot as an endorsed candidate for another political party. The Court’s reasoning here was that the compelling interest in preventing fraud and voter confusion outweighed any First Amendment claims to ballot access.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.