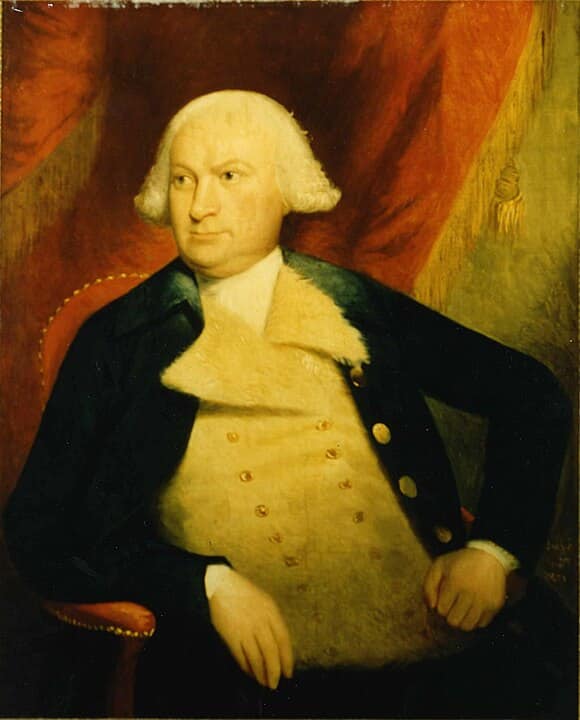

Oliver Ellsworth (1745-1807) was the third chief justice of the United States. He was appointed by President George Washington and served from 1796 to 1800.

Ellsworth, from Connecticut, attended Yale and the College of New Jersey (today’s Princeton) and read law before becoming an attorney. He served as a member of the Continental Congress, as a Connecticut judge, as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, as a U.S. Senator.

Ellsworth was one of three individuals whom President John Adams appointed to negotiate a treaty with France that resulted in the notorious XYZ Affair.

Ellsworth helped in development of Constitution

Ellsworth played an important part at the Constitutional Convention where he was one of the authors of the Connecticut Compromise that provided for equal state representation in the U.S. Senate, and representation in the U.S. House of Representatives according to population. Less successfully, Ellsworth had favored the plan that would have included members of the judiciary with the executive in a Council of Revision. Ellsworth served on the important Committee of Detail at the Convention.

Although he returned to his state to attend to his judicial duties before the delegates signed the Constitution, he supported the document during ratification debates and was a leader among the Federalist Party members in the Senate.

As a senator, Ellsworth took the lead in drafting the Judiciary Act of 1789, which provided a blueprint for the federal courts system that remains, in modified form, today. Ellsworth also played a role in the adoption of the First Amendment and other provisions within the Bill of Rights and helped secure ratification of the controversial Jay Treaty.

During ratification of the U.S. Constitution, Ellsworth had joined other Federalists in arguing that a bill of rights was unnecessary because the Constitution had not granted Congress any powers to interfere with such rights. Ellsworth further defended the constitution’s prohibition of religious tests for federal offices as a way “to exclude persecution, and to secure . . . the important right of religious liberty” (Bird 2016, 239). Although he argued for freedom of conscience, he did think that governments had power to prohibit “grow immoralities and impieties” as well as “profane swearing, blasphemy, and professed atheism” (Bird 2016, 239-240).

Ellsworth defended constitutionality of Sedition Act of 1798

After the adoption of the Sedition Act of 1798, Ellsworth offered Secretary of State Timothy Pickering an informal advisory opinion at odds with his earlier view that the federal government would have not power to interfere with freedoms of speech and press. He argued that the law was constitutional because it permitted truth as a defense. Even prior to the adoption of the law, Ellsworth had warned a grand jury of the threat of seditious speech. He issued similar words to a grand jury after the Sedition Act was adopted, but did not, because of his service as a diplomat to France, have the opportunity of trying prosecutions under the act as chief justice.

Ellsworth favored an established state church

Ellsworth was an orthodox Calvinist who had experienced a conversion experience, and believed strongly in God’s providence, in the fallenness of human nature, and in the obligation of good leaders to rule virtuously. Near the end of his life, he and fellow members of the Connecticut Missionary Society published “A Summary of Christian Doctrine and Practice.”

Whereas Thomas Jefferson and James Madison had favored separation of church and state in Virginia, Ellsworth thought that, at least at the state level, it was appropriate for the state to use tax money to support religion. When Connecticut Baptists petitioned to disestablish its church, Ellsworth headed a committee that denied their appeal, reputedly throwing the petition on the floor, stepping on it and proclaiming, “This is where it be belongs” (Casto 1994, 522). In its subsequent report, the committee decided that “Institutions for the promotion of good morals, are objects of legislative provision and support: and among these, in the opinion of the committee, religious institutions are eminently useful and important” (Casto 1994, 525).

Ellsworth does not appear to have ruled on any church/state issues while on the Supreme Court from which he resigned in 1800 citing health concerns. He was succeeded as Chief Justice by John Marshall.

John R. Vile if a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.