One important form of symbolic speech and protest in the United States that began before the Revolutionary War and continued long after the adoption of the First Amendment was the erection of liberty poles.

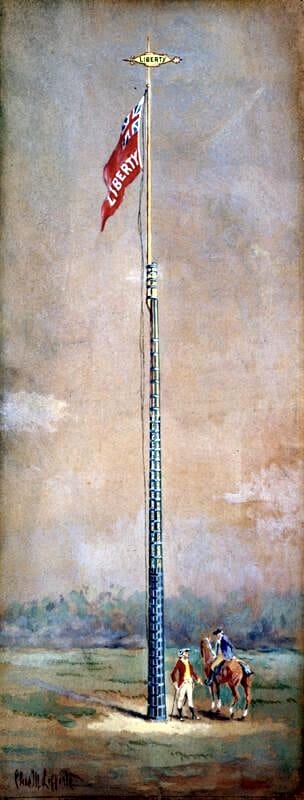

Such poles have some association with Liberty Trees, like the elm near the Boston Commons where Patriots gathered in protest against British tax policies (Trickey 2016). Liberty poles consisted of very tall tree trunks typically erected in public places, and often containing placards or banners protesting governmental policies.

Liberty poles considered collective act of defiance

Liberty poles were more common in the New England states than elsewhere. They were rarely found in the deep South where such public invocations of liberty might stir slave rebellions.

Not surprisingly, British soldiers often chopped liberty poles down as Patriots sought to defend them. Constructing a pole was generally considered to be a collective act of defiance that enabled common people with little other influence in government to express their sentiments. Once Congress adopted the Declaration of Independence, liberty poles generally disappeared, probably because citizens had found a more active and productive means of resistance through military service.

Liberty poles in 1790s protested local regulations

Such poles were resurrected in the 1790s, and were often connected to “regulation” movements, especially within North Carolina and Pennsylvania. These movements protested local taxes on whiskey, stamps, or other items, taxes that generally fell more heavily on the poor and on small farmers than on large landowners.

Whereas liberty poles prior to the Revolution had targeted a government with a parliament in which colonists were unrepresented, regulators were protesting against a government built upon “We the People” in which they were represented. The poles were thus more problematic, although they could arguably be justified as a form of freedom of expression protected by most state bills of rights as well as by the First Amendment.

Federalist Party considered liberty poles as acts of sedition

Especially during the Whiskey Rebellion, members of the Federalist Party believed that the erection of liberty poles was seditious and feared that they would undermine America’s foreign policy by highlighting internal division and national weakness.

The Federalist-backed Sedition Act of 1798, which limited criticisms of the government and its leaders, prompted Democratic-Republicans to erect numerous liberty poles, and often precipitated physical altercations between members of the two parties some of which resulted in criminal prosecutions and convictions (Smith 1955). Democratic-Republican leaders supported opposition to the Sedition Act but sought to distance themselves from the violence that sometimes surrounded the poles and attempts to destroy them.

Liberty poles eventually became symbols of candidate support

After the election of 1800 brought Thomas Jefferson and other Democratic-Republicans to power, the poles were more frequently erected “to celebrate the government’s achievements and demonstrate support for elected officials” rather than as acts of protest (Lurie 2023, 196).

In time, both parties began erecting liberty poles, typically capped by a placard with the names of their candidates. Poles began a means of mobilizing individuals to show support and vote for party candidates rather than acts of defiance against governmental policies. Democrat supporters of Andrew Jackson raised “Hickory Poles” in his honor, whereas Whig supporters of Henry Clay raised “Clay poles” or “Ash poles,” the latter referring to Clay’s Ashland Estate (Lurie 2023, 131).

Liberty poles replaced by other forms of protest

Long after the practice of constructing liberty poles had died out, in 1921, the New York Sons of the American Revolution erected a monument to liberty poles in City Hall Park in New York to honor the contribution that such poles had played during the Revolutionary War.

Modern protestors have chosen to sign petitions and engage in parades, marches, sit-ins and other forms of symbolic speech rather than in pole raising. A whiskey distiller in Washington, Pennsylvania that manufactures Liberty Pole Spirits has sponsored some pole commemorations to sell its product (Lurie 2013, 146).

Shira Lurie, who teaches at St. Mary’s University in Nova Scotia, Canada, has written an engaging and definitive work on the subject, entitled “The American Liberty Pole: Popular Politics and the Struggle for Democracy in the Early Republic.”

John R. Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.