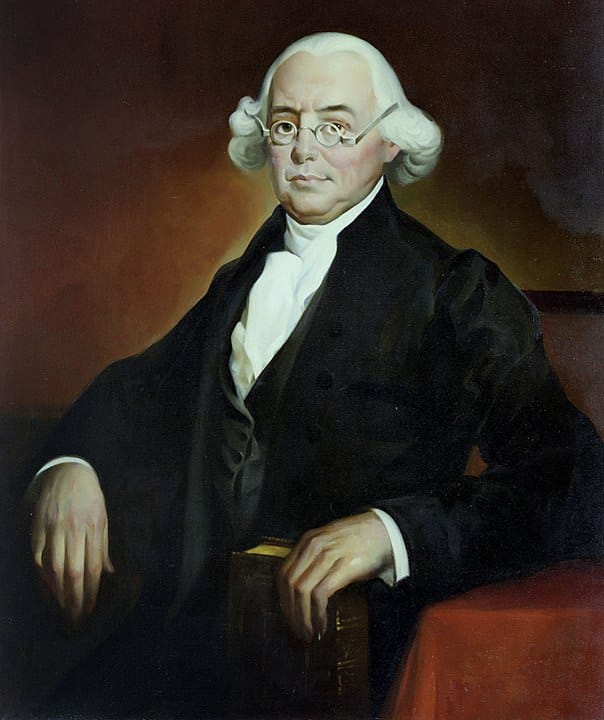

James Wilson (1742-1798), who was born in Scotland and emigrated to the United States at the age of 23, studied law under John Dickinson, and went on to become one of the leading attorneys in Pennsylvania.

One of America's founders, he was appointed as one of the early Supreme Court justices by George Washington. His writings and law lectures suggest he did not support seditious libel, an issue that became a major contention between Federalists and the opposition party in the late 18th century.

Wilson authored a manuscript entitled “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament,” which was published in 1768, denying parliament’s right to tax the colonies.

He served from 1775 to 1777 as a delegate to the Continental Congress where he signed the Declaration of Independence.

James Wilson was influential in development of U.S. Constitution

Wilson was one of the most influential delegates to the U.S. Constitutional Convention of 1787. There he favored strengthening the national government, direct election of the president, representation on the basis of population in both houses of Congress, a strong presidency, and presidential appointment of federal judges and justices.

He made a widely quoted speech on behalf of ratification of the U.S. Constitution and later successively worked to replace the Pennsylvania Constitution, which he thought inadequately embodied the idea of separation of powers.

Wilson served as a law professor at the University of Pennsylvania and delivered a series of publicized lectures on American law, which George Washington and other prominent statesmen attended.

In 1789, President George Washington appointed Wilson to the Supreme Court, where he served until 1798. The court did not hear any First Amendment issues while Wilson was a justice, but he distinguished himself in other opinions. Unfortunately, Wilson engaged in land speculation that resulted in financial ruin, was imprisoned for a time for his debts, and actually fled to North Carolina to avoid his creditors.

James Wilson spoke on liberty of the press

As a Federalist supporter of the Constitution, Wilson initially argued, in accord with other supporters, that the federal bill of rights was unnecessary. This was not because he opposed rights like those that would be included in the First Amendment but because he did not believe that the document enumerated any powers that would justify the suppression of such rights.

In his famed State House Yard Speech of Oct. 6, 1787, Wilson thus observed that “everything which is not given” to the national government is reserved, and that “it would have been superfluous and absurd to have stipulated with a foederal body of our own creation, that we should enjoy those privileges, of which we are not divested either by the intention of the act, that has brought that body into existence.” Referring specifically to “the liberty of the press,” he asked, “what control can proceed from the foederal government to shackle or destroy that sacred palladium of national freedom?” (Wilson, I, 172).

At the Pennsylvania ratifying convention, Wilson made a similar argument. He explained that “What is meant by the liberty of the press is, that there should be no antecedent restraint upon it; but that every author is responsible when he attacks the security of welfare of the government or the safety, character, and property of the individual” (Bird 2015, 172). Historian Wendell Bird points out that, although this seems to accept the limited view of freedom of press by British jurist William Blackstone, Wilson was writing before the adoption of the First Amendment and was referring to existing state laws on the subject (Bird 2015, 172-173).

In drafting the Pennsylvania Declaration of Rights in 1789, Wilson proposed that:

The printing presses shall be free to every person who undertakes to examine the proceedings of the legislature or any branch of government, and no law shall ever be made restraining the right thereof. The free communication of thoughts and opinions is one of the most invaluable rights of man, and every citizen may freely speak, write and print, being responsible for the abuse of that liberty. (Bird 2015, 174).

Part of Wilson’s opposition to Pennsylvania’s earlier constitution was that it required individuals to take an oath supporting it, which he feared would take away their right of dissent (Bird 2015, 181). Moreover, although apparently allowing room for prosecution of unfounded libels of falsehood directed at individuals, Wilson did not endorse the idea of laws of seditious libel punishing individuals for criticizing he government or its agents (Bird 2015, 174).

In a broadside, Wilson further identified “the great and fundamental principles of free government” with “Liberty of Conscience—Trial by Juries—Freedom of the Press—Annual Elections—and the Division and Rotation of Offices” (Bird 2015, 177). In his lectures on law, he further lionized both Lord Baltimore and William Penn for their roles in supporting religious liberty in their colonies (Wilson I, 434).

Wilson did not support English law of seditious libel

In Wilson’s famed lectures of law, he supported the idea of natural rights and further separated himself from the English law of seditious libel. More specifically, he rejected Blackstonian arguments that libel of a public official was greater than that of a private man; that truthful statements could be considered libelous; and that words that injure individuals also injure the public as a whole (Wilson, 2007, II: 1135-1136). Wilson also favored allowing jurors to decide both matters of law and fact in libel cases.

Wilson left the Supreme Court prior to the time when he had occasion riding circuit to comment on the Sedition Act of 1798, but the most thorough reviewer of Wilson’s views on the subject does not believe he supported it (Bird 2015, 436-444).

John R. Vile is a professor of history and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.