James Madison (1751–1836), the chief author of the Bill of Rights and thus of the First Amendment, was the foremost champion of religious liberty, freedom of speech, and freedom of the press in the Founding Era.

Madison played a central role in drafting, explaining, and ratifying the Constitution; after it was ratified he sought to reassure its critics by adding guarantees of fundamental liberties.

His life’s work, as statesman and as political theorist, was to secure the American revolutionary experiment by guarding against its own potential weaknesses and excesses. Republican government was endangered, he believed, if unrestrained majorities violated the rights of individuals or if elected officials were immune from the scrutiny of a free press.

Madison drafted religious liberty language for Virginia

Madison was born to a well-established Virginia planter family. In 1769 he enrolled at the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) and came under the intellectual and political influence of the college’s new president, John Witherspoon, whose stated goal was to foster a spirit of liberty and free enquiry and who opened the curriculum to currents of religious and political dissent.

After returning to Virginia, Madison joined passionately in the political ferment of the impending revolution and was appalled to find that his state was jailing ministers who were not licensed by the established church. In the spring of 1776 he served on a committee preparing a Declaration of Rights for Virginia’s new constitution. He amended draft language on religious liberty to remove the weaker word toleration and instead to declare “that all men are equally entitled to enjoy the free exercise of religion, according to the dictates of conscience.”

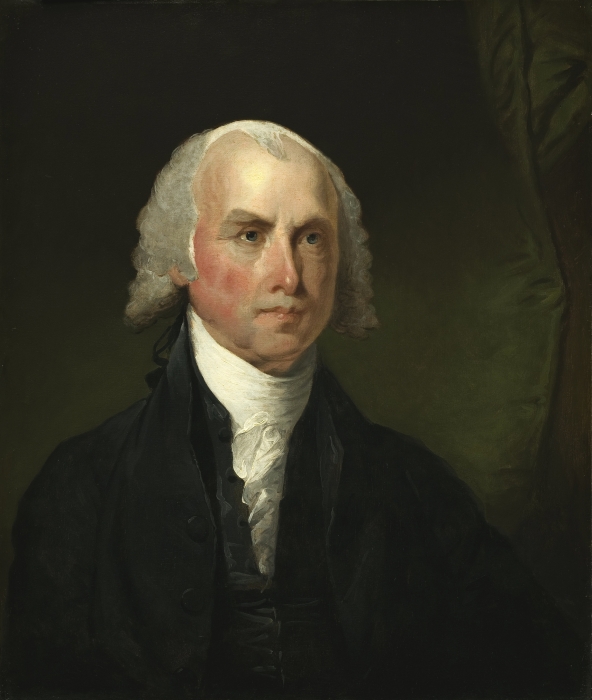

Madison played a crucial role in calling the Constitutional Convention of 1787, in Philadelphia, and in shaping deliberations during the convention. Like most other delegates, he sought to remedy the weaknesses of the federal government under the Articles of Confederation. But Madison was equally concerned with remedying the internal injustices of states, the tendency of state-level majorities to violate the rights of individuals and minorities. (Image via Library of Congress, painted by Charles Wilson Peale in 1783, public domain)

Madison deterred a bill that established Christianity as the Virginia state religion

Madison served in the Continental Congress from 1780 to 1783, where he learned firsthand the weaknesses of the federal government under the Articles of Confederation. He then served in the Virginia Assembly, where, in 1785, he produced his first great political pamphlet, the “Memorial and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments.” The target of the pamphlet was a bill before the Virginia Assembly supported by Gov. Patrick Henry that would have laid a general tax to pay Christian teachers a modest salary. The bill would not have established any one denomination (all Christian churches were eligible for the funds), but it would have made Christianity the established religion of the state.

Madison considered the bill a “dangerous abuse of power”; he reasoned that if government could establish Christianity over other religions, then it would also have the power to elevate one Christian group over another. Madison believed that religion was a matter of individual conscience and that giving legislators control over religious belief would inevitably lead to violation of other basic rights: “It is proper to take alarm at the first experiment on our liberties.” Madison succeeded in defeating the religious assessment bill and then spearheaded passage, in 1786, of Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom.

Madison played crucial role in developing Constitution

Madison played a crucial role in calling the Constitutional Convention of 1787, in Philadelphia, and in shaping the Virginia Plan, which offered a clear alternative rather than mere alterations to the Articles of Confederation. He also actively participated in deliberations during the convention.

Like most other delegates, he sought to remedy the weaknesses of the federal government under the Articles of Confederation. But Madison was equally concerned with remedying the internal injustices of states, the tendency of state-level majorities to violate the rights of individuals and minorities. Madison was a slaveholder, and although he appeared to recognize the evils of this institution, he was far more interested in strengthening the Union at the Convention than in dealing with this issue, and he was not in a financial position to free his slaves upon his death.

Despite his concerns over state injustices, Madison failed in his attempt to include in the Constitution a federal veto on state laws in order “to secure individuals against encroachments on their rights.” Nevertheless, during the ratification debate Madison, in which he helped author the Federalist Papers, he claimed that the federal government under the proposed Constitution would better protect the rights of individuals and minorities, because (as he argued in Federalist No. 10) national legislation would be crafted by more political parties and interests than existed within the states, making it more difficult for any one faction to carry out its “plans of oppression.” Madison was especially concerned with violation of property rights, but he also spoke of religious zeal as a dangerous source of conflict and oppression. Madison was a key figure at the Virginia ratifying convention, where his opponents included Patrick Henry and George Mason.

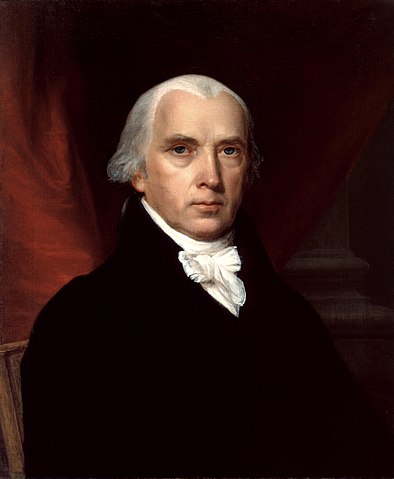

Despite his commitment to individual liberties, Madison opposed making inclusion of a bill of rights a precondition for ratification of the Constitution. He also doubted that mere “paper barriers” against violating basic rights were sufficient protection. A combination of electoral politics and a change in Madison’s own thinking, however, turned him into an active proponent of a federal bill of rights. In a hard-fought 1788 campaign for a seat in the First Congress, Madison promised to support a bill of rights, and in June 1789 he introduced in Congress a series of proposed amendments that formed the core of what became the Bill of Rights in the Constitution. (Image via the White House Historical Association, painted by John Vanderlyn in 1816, public domain)

Madison was a proponent of a bill of rights

One of the most influential objections to the proposed Constitution was that it lacked a bill of rights. Thomas Jefferson raised this issue in a December 1787 letter to Madison. Several states, including Virginia, appended to their ratification of the Constitution a long list of recommended amendments, including protection of basic rights and liberties. When the First Congress convened in April 1789, North Carolina and Rhode Island had not yet ratified the Constitution, and many citizens in the 11 ratifying states still feared this new federal government was a threat to liberty.

Despite his commitment to individual liberties, Madison opposed making inclusion of a bill of rights a precondition for ratification of the Constitution. He also doubted that mere “paper barriers” against violating basic rights were sufficient protection. A combination of electoral politics and a change in Madison’s own thinking, however, turned him into an active proponent of a federal bill of rights. In a hard-fought 1788 campaign for a seat in the First Congress against none other than James Monroe, Madison promised to support a bill of rights, and in June 1789 he introduced in Congress a series of proposed amendments that formed the core of what became the Bill of Rights in the Constitution.

In introducing his proposed amendments, Madison particularly emphasized the role of public opinion in a republic. Even if the Constitution did not actually threaten liberty, many people believed it might have that effect, and it was important to allay their fears. Moreover, the wide support for a bill of rights expressed in state ratifying conventions promised to enlist public opinion in support of individual liberties. Paper barriers alone would not prevent violation of rights. But if basic rights were declared in the Constitution, they would influence public opinion against their abridgement and help restrain intolerant majorities. As Thomas Jefferson had pointed out, such guarantees would also provide a basis for individuals to seek protection for their rights in courts.

Madison proposed more descriptive First Amendment

Madison’s proposal for what eventually became the First Amendment is broadly consistent with the final product but in some respects more descriptive:

“The civil rights of none shall be abridged on account of religious belief or worship, nor shall any national religion be established, nor shall the full and equal rights of conscience be in any manner, or on any pretext infringed.

“The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.

“The people shall not be restrained from peaceably assembling and consulting for their common good; nor from applying to the legislature by petitions, or remonstrances for redress of their grievances.”

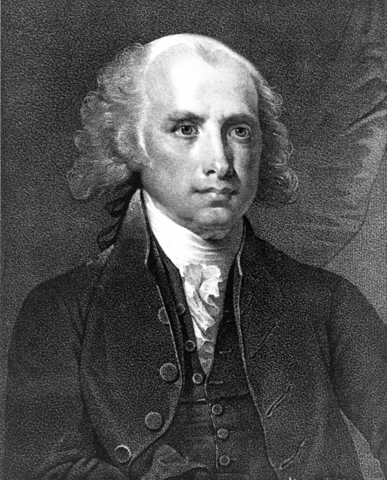

In one important respect what Madison proposed was very different from what ultimately made it into the Bill of Rights. Madison envisioned a bill of rights that would have prevented both the federal government and the states from violating basic liberties. The Bill of Rights as ultimately ratified restricted only the federal government. (Image via Library of Congress, created by Pendleton’s Lithography circa 1828, public domain)

Madison wanted the Bill of Rights to apply to the states

In one important respect what Madison proposed was very different from what ultimately made it into the Bill of Rights. Madison’s fifth resolution, which he thought was the most important amendment of all, would have provided that “No state shall violate the equal rights of conscience, or the freedom of the press, or the trial by jury in criminal cases.” The Bill of Rights as ultimately ratified restricted only the federal government.

Madison envisioned a bill of rights that would have prevented both the federal government and the states from violating basic liberties. In this respect Madison anticipated the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) and the subsequent process of incorporation whereby key Bill of Rights protections were made binding on the states.

During the 1780s Madison had believed the principal threats to basic liberties came from the states, not from the federal government. Events of the 1790s persuaded him that an unchecked federal government was equally dangerous. He and his close friend Thomas Jefferson subsequently became the leaders of the Democratic-Republican Party, which opposed many policies of the first two Federalist presidents, including the establishment of a national bank.

Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts

In 1798 the Federalist-dominated Congress, responding to fears of foreign subversion and intense domestic partisanship, passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Sedition Act made it a crime to “write, print, utter or publish . . . any false, scandalous, and malicious writing or writings” that would have the effect of bringing office holders “into contempt or disrepute” in the opinion of “the good people of the United States.”

Supporters of the law, citing English common law precedent, claimed that the First Amendment prohibition on abridging the freedom of the press forbade only “previous restraint on printed publications,” not subsequent punishment for what one had printed. The Sedition Act also provided that those charged were absolved if they could prove the truth of what they had asserted in their publications.

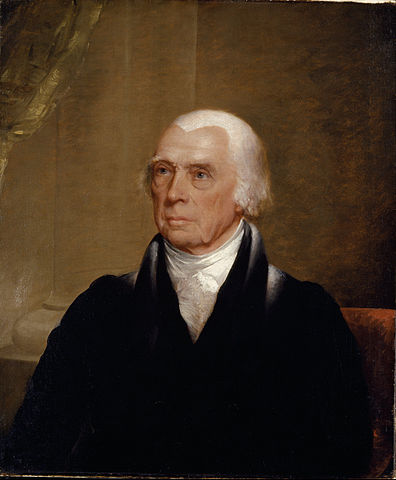

During his long retirement Madison became the last surviving major figure of the founding generation. He self-consciously assumed the role of guardian and interpreter of the revolutionary experiment — or what he had once named “the sacred fire of liberty” — for a new and turbulent generation of Americans. (Image via National Portrait Gallery, painted by Chester Harding circa 1830, public domain)

Madison denounced the Sedition Act

In his Virginia Resolutions of 1798, and in the Report of 1800 that further explained those resolutions, Madison denounced the Sedition Act, and its restrictions on freedom of speech and press, as a flagrant violation of the First Amendment and as a fundamental threat to republican government.

Madison denied that the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of the press meant only freedom from prior restraint on publications. English common law understandings of press liberty, Madison argued, were inapplicable to a republic like the United States founded on the principle that “the people, not the government, possess the absolute sovereignty.” In order to hold public officers responsible in a republic, people must be able freely to discuss public officials and their policies. If office holders have violated the people’s trust, they should not be able to shield themselves from criticism by restricting the press.

Madison argued that the opportunity to prove that one’s writings were true was inadequate protection. First, it is extremely difficult for anyone to demonstrate “the full and formal truth” of every publication, and, second, the obvious purpose of the law was to punish political opinions, not to correct misstatements of fact. Madison admitted that freedom of the press could be abused, but he thought it was better to leave a few “noxious branches” than to cut away the “proper fruits.”

Madison was 4th U.S. president

In the early days of the republic, Madison served as secretary of state under Thomas Jefferson, during whose administration the United States made the Louisiana Purchase. He then served as president himself for two terms, and was in turn succeeded by his Secretary of State, James Monroe.

His presidency (1809–1817) was clouded by his failure adequately to prepare the country for the War of 1812, but he demonstrated his commitment to the First Amendment by refusing to muzzle the press despite intense domestic opposition to the war. He also vetoed two pieces of legislation that he considered unconstitutional financial support for religious institutions.

As president, Madison appointed Joseph Story and Gabriel Duvall to the U.S. Supreme Court. In addition to being influential, Story wrote some of the most important commentaries on the U.S. Constitution.

During his long retirement, which included his participation in a convention to revise the Virginia Constitution, Madison became the last surviving major figure of the founding generation. He and his vivacious wife Dolley, who would move to the nation’s capital after his death, entertained many guests at their plantation near Orange, Virginia, called Montpelier, which has been restored and is open to the public. Madison self-consciously assumed the role of guardian and interpreter of the revolutionary experiment — or what he had once named “the sacred fire of liberty” — for a new and turbulent generation of Americans. Madison’s records of the debates of the Constitutional Convention, published after his death, remain the single-most important source for detailing these deliberations.

This article was originally published in 2009. James H. Read is Professor of Political Science at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University of Minnesota. He is the author of Power versus Liberty: Madison, Hamilton, Wilson, and Jefferson (2000) and Majority Rule versus Consensus: The Political Thought of John C. Calhoun (2009), as well as several articles and book chapters in the field of American political thought. He has recently published "Sovereign of a Free People: Abraham Lincoln, Majority Rule, and Slavery."