The Supreme Court in Heller v. New York, 413 U.S. 483 (1973), vacated and remanded an obscenity conviction in light of its decisions four days earlier in Miller v. California and Paris Adult Theatre I v. Slaton, where it had set new standards for determining which materials were obscene, and therefore unprotected by the First Amendment. The Court did so even though it upheld a warrant that a New York judge had issued confiscating a copy of the sexually-oriented film, Blue Movie.

Heller arrested after showing sexually-oriented film

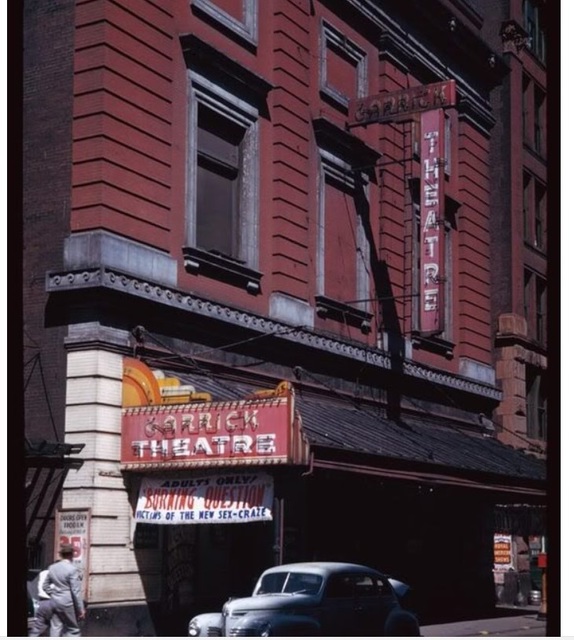

Heller, the manager of a commercial movie theater, and others connected with the establishment, had been arrested after a judge had viewed the movie, which contained scenes depicting a nude couple engaged in ultimate sexual acts. The judge had also seized a warrant for the seizure of a copy of the movie.

Court said judge could confiscate movie copy for evidence

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger agreed that the judge in the lower court could issue a warrant without first conducting an adversary hearing on its probable obscenity. The present case did not involve an instance of “final restraint,” as in United States v. Thirty-seven Photographs (1971) or Freedman v. Maryland (1965), since in Heller the judge had seized only one copy of the film for evidentiary purposes. Neither did he confiscate and destroy vast quantities of books of materials as in A Quantity of Books v. Kansas (1964). The record also gave no indication that this was the theater’s only copy.

Dissenters said obscenity law in question violated First Amendment

Justice William O. Douglas wrote a dissent, which also applied to Roaden v. Kentucky (1973), stating that the obscenity law in question violated the First Amendment. Justice William J. Brennan Jr. also wrote a dissent, joined by Justices Potter Stewart and Thurgood Marshall, arguing that the law was “unconstitutionally overbroad” and therefore facially invalid.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.