In Federal Communications Commission v. Pacifica Foundation, 438 U.S. 726 (1978), the Supreme Court allowed the government to regulate indecent speech over the broadcast medium.

The decision reaffirmed the notion that the government has a freer hand to regulate the broadcast medium than other forms of media.

FCC said radio station could face sanctions for playing program with profanity

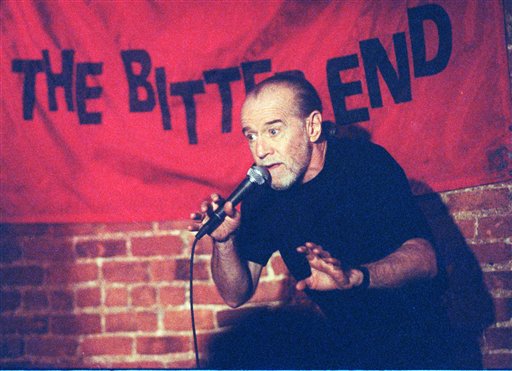

The case began in October 1973 when a man, who was riding in a car with his minor son, heard an afternoon radio broadcast of comedian George Carlin’s “Filthy Words” monologue.

The man filed a complaint with the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), contending that minors should not be exposed to such profane and indecent comments. The FCC agreed and issued an order in February 1975 pointing out that the Pacifica Foundation, which owned the New York radio station that broadcast Carlin’s monologue, could have been subjected to administrative sanctions.

The FCC did not impose formal sanctions, but placed a letter in the station’s file that could be used to enhance future punishments. The commission determined that “the language as broadcast was indecent and could be prohibited by 18 U.S.C. section 1464,” which enjoins the radio broadcast of “obscene, indecent or profane” speech.

Court ruled in favor of FCC

Pacifica appealed to the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals, which ruled 2-1 that the FCC had engaged in improper censorship. The FCC then appealed to the Supreme Court, which ruled in its favor 5-4.

In his opinion for the Court, Justice John Paul Stevens rejected Pacifica’s statutory and constitutional challenges. The statutory challenges centered on whether 47 U.S.C. section 326 authorized the prohibition of indecent speech and whether 18 U.S.C. section 1464 reached indecent speech or simply obscenity. Stevens concluded that the statutory language empowered the FCC to regulate indecent speech.

Court said broadcast media had limited First Amendment protection

Stevens characterized the constitutional issue as “whether the First Amendment denies government any power to restrict the public broadcast of indecent language in any circumstances.”

Stevens reasoned that the government had greater power to regulate the sexual speech at issue in this case for at least two reasons based on content and context.

- First, the sexual speech at issue in this case had lower value and was not entitled to as much protection as political speech.

- Second, the speech took place in the broadcast medium that “has received the most limited First Amendment protection.”

He reasoned that the broadcast medium was “uniquely accessible to children,” and he emphasized the indecent speech was broadcast during daytime hours.

Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., joined by Justice Harry A. Blackmun, concurred and agreed with much of Stevens’s analysis except the proposition that the First Amendment allowed the government to decide that certain forms of speech are more “valuable” than others.

Dissenters disagreed on First Amendment, statutory grounds

Justice William J. Brennan Jr., joined by Justice Thurgood Marshall, dissented vehemently, accusing the majority of “misapplication of fundamental First Amendment principles.” Brennan contended that if the First Amendment protected Robert Paul Cohen from wearing a jacket bearing the words “Fuck the Draft” in a California courthouse, at issue in Cohen v. California (1971), then it should also protect the radio station in this instance.

Brennan criticized the plurality for allowing the suppression of nonobscene speech that adults and older minors should be able to listen to if they wished. He also accused the majority of failing to appreciate “cultural pluralism”: “It is only an acute ethnocentric myopia that enables the Court to approve the censorship of communications solely because of the words they contain.”

Justice Potter Stewart, joined by Justices Byron R. White, Brennan, and Marshall, dissented on statutory grounds. Stewart argued that the prohibition in 18 U.S.C. section 1464 against “obscene, indecent or profane language” should be limited to reaching just obscene expression, as the Court had done with a similar federal statute in Hamling v. United States (1974).

In 2008 the Court would revisit the issue of broadcast indecency in Federal Communications Commission v. Fox Television Stations.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.