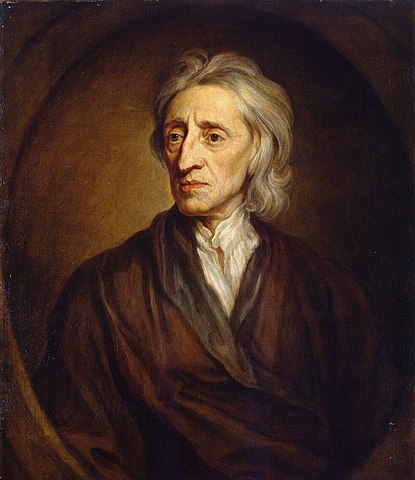

The American revolutionary generation drew many of its ideas from the English philosopher John Locke (1632–1704). Often credited as a founder of modern “liberal” thought, Locke pioneered the ideas of natural law, social contract, religious toleration, and the right to revolution that proved essential to both the American Revolution and the U.S. Constitution that followed.

Locke argued against the ‘paternal’ supervision of government

Locke was born into a prosperous family that held parliamentary sympathies during the English Civil War. Trained in medicine at Oxford, he worked as a family physician and adviser for Anthony Ashley Cooper (later to be the Earl of Shaftesbury), who emerged as the most prominent leader of the Whig opposition after the “Restoration” of the Stuart monarchy in 1660. During political exile in Holland, Locke refined his most famous works of philosophy and political theory: the Essay concerning Human Understanding and the Two Treatises of Government, respectively. Both works are based on the premise that since human beings are capable of exercising reason, they can be trusted to manage their own affairs without the “paternal” supervision of government, as he argues in his Second Treatise (1952 edition: 30).

Locke published these works only after the Glorious Revolution of 1688, when Parliament had deposed the absolutist James II in favor of a constitutional monarchy, and even then he kept the authorship of the Treatises anonymous. Whereas the First Treatise dismantles the philosophy of the “divine right of kings,” the more influential Second Treatise lays out Locke’s positive theory of government. It proved essential to the American founders, although later historians have engaged in wide-ranging debates as to whether Locke was chiefly a radical libertarian, an apologist for capitalism, a social democrat, a moral individualist, an atheistic hedonist, or a deeply religious reformer.

Locke said mankind’s ‘original’ condition is ‘a state of perfect freedom’

The core ideas in the Second Treatise are deceptively simple. To understand government, Locke begins with mankind’s “original” condition, which he describes as a prepolitical “state of nature”: men and women in “a state of perfect freedom to order their actions and dispose of their persons and possessions as they think fit, within the bounds of the law of nature, without asking leave or depending upon the will of any other man.”

This is also a state of equality: absent any natural hierarchy, each and every human being is born with equal rights to “life, liberty, and estate,” all of which qualify as “property,” the most essential natural right (1952: 48). Nonetheless, the state of nature is an undesirable condition; as creatures of passion, individuals tend to be biased in their own favor and lack both a neutral “umpire” to decide disputes and an impartial enforcer to carry out natural law (1952: 49).

When the state of nature descends into a “state of war,” these free and equal individuals rationally choose to form a social contract, one grounded in mutual “consent” and guided by the “determination of the majority” (1952: 55). Individuals give up their natural rights to judge disputes and enforce the law of nature, and in thus giving up their individual rights they create the original powers of government: the legislative and executive, a distinction that Locke uses to justify a fundamental separation of powers. If either branch exceeds its proper authority, the people retain a right to revolt after a “long train of abuses” (1952: 126).

Americans were influenced directly by Locke’s principles

American revolutionaries often drew a direct line between Locke’s principles and their own. They frequently cited him during the Stamp Act protests and the Pamphlet War. Thomas Jefferson, describing his writing of the Declaration of Independence, commented that “All its authority rests then upon the harmonizing sentiments of the day,” taken from “the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c.” (1999 edition of his Political Writings: 148).

Although Locke’s name was invoked less often during the framing of the Constitution, his concerns about the protection of “life, liberty, and estate” were universally shared by the delegates in Philadelphia, who worried that the state governments had failed in this basic Lockean task. Prominent Anti-Federalists, disappointed by the initial lack of a bill of rights, appealed to Locke’s philosophy as well. As Richard Henry Lee wrote, “There are certain unalienable and fundamental rights, which in forming the social contract, ought to be explicitly ascertained and fixed” (1985 edition: 232).

Locke defended religious toleration

Locke’s most direct contribution to the First Amendment lies in his defense of religious toleration. Although toleration in the American colonies predates Locke, especially in the pluralistic middle colonies and in the writings of Rhode Island’s Roger Williams, Locke lent considerable support to the cause in his Letter concerning Toleration (1689). As a Christian rationalist, Locke renounced the ideas that faith can be forced and that piety demands a particular organizational or doctrinal orthodoxy.

If government exists simply to secure property, it can have no say over religion: “the Care of Souls is not committed to the Civil Magistrate, any more than to other Men. . . . Nor can any such Power be vested in the Magistrate by the consent of the People; because no man can so far abandon the care of his own Salvation, as blindly to leave it to the choice of any other” (1983 edition: 26). He added that “the Church itself is a thing absolutely separate and distinct from the Commonwealth. The boundaries of both are fixed and immovable. He jumbles Heaven and Earth together . . . who mixes these two” (1983: 33).

Although Locke, responding to the fevered religious battles of his day, conceded the impracticality of extending tolerance to atheists, who he thought lacked morality, or Catholics, who he felt despised the rule of law, he still sought to distance religious belief from the coercive and corrupting force of the state. For in Locke’s opinion, it was politically imposed unity, rather than religious diversity, that caused conflict.

This article was originally published in 2009. Robb A. McDaniel is an Associate Professor at Middle Tennessee State University.