Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. authored the unanimous Supreme Court decision in Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919), sustaining socialist leader Eugene V. Debs’s conviction under the Sedition Act of 1918.

Debs was a well-known public figure; he had received almost 1 million votes when he ran for President in 1912. On June 16, 1918, Debs gave a speech outside the Canton, Ohio, prison, where he had visited three Socialists convicted of violating the Sedition Act.

Debs arrested for speech even though he avoided illegal advocacy

Before an audience of about 1,200 people, Debs offered his support for the prisoners, saying that they were paying the price for “seeking to pave the way to better conditions for all mankind.” Debs, a pacifist, condemned the ongoing war but took care not to advocate any illegal activity and even commented to his audience that he had to be prudent with his word choice.

He was arrested for the speech, however, and was convicted of obstructing military recruitment and enlistment. Sentenced to 10 years in prison, Debs appealed his conviction, arguing his speech was protected by the First Amendment.

Just one week before the Debs opinion was announced, Holmes had introduced the “clear and present danger” test in Schenck v. United States (1919), suggesting that judges must examine the context in which the speech was made, rather than the “bad tendency” of the words alone as had been traditional in free-speech cases.

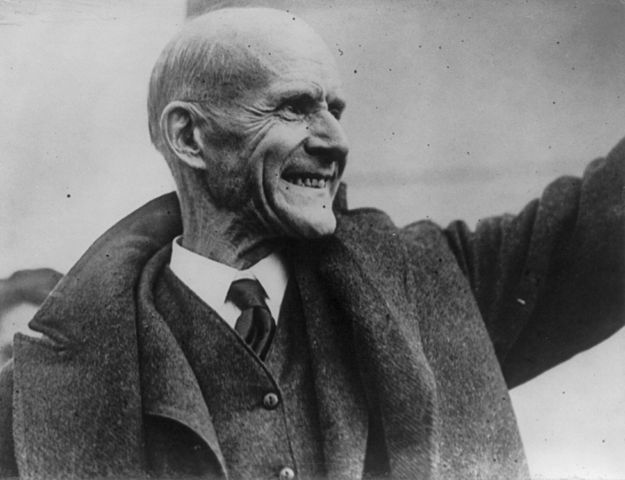

Eugene V. Debs giving a speech in Chicago in 1912. In 1918, Debs was jailed for a speech given in Canton, Ohio. He was convicted of obstructing military recruitment and enlistment. Sentenced to 10 years in prison, Debs appealed his conviction, arguing his speech was protected by the First Amendment. However, the Court upheld the conviction. (Image via Wikimedia Commons, public domain)

Holmes focused on Debs’s underlying intent in his speech

In Debs, however, Holmes did not address the circumstances that may have led Debs’s speech to be potentially dangerous to recruitment. Instead, Holmes determined that even though Debs did not expressly advocate draft resistance, his intent and the general tendency of his words were together sufficient for a jury to convict him fairly.

According to Holmes, Debs’s warning that he had to be careful with his words meant that the audience was free to infer an underlying meaning. The decision did not discuss potentially salient differences between Debs and Schenck; for example, Schenck had addressed draft inductees, whereas Debs had spoken to a general audience.

Scholars generally view Debs as a low-water mark in the protection of free speech during wartime.

Holmes moved to a strong defense of First Amendment eight months later

One of the pressing questions in the history of the First Amendment concerns how Holmes moved from Debs in March 1919 to the strong defense of free speech he penned eight months later in his dissent in Abrams v United States (1919).

Holmes’s correspondence at the time reveals that although he never questioned the correctness of his decision, he was unhappy that the federal government had chosen to prosecute Debs and that he had been chosen to write the opinion.

Discussions over the value of free speech and dissent with Judge Learned Hand and political science professor Harold Laski, combined with an influential article by Ernst Freund criticizing the Debs decision in the May issue of The New Republic, may have led Holmes to reevaluate the relationship between political liberty and criticism of the government, as well as his own commitment to free speech.

In 1920, while in prison, Debs again ran for President and received almost 1 million votes. President Warren G. Harding commuted his sentence in 1921.

This article was originally published in 2009. Douglas C. Dow, Ph.D., is a professor at the University of Texas at Dallas specializing in political theory, public law, legal theory and history, and American politics.