Conscientious objection to military service refers to the position taken by individuals who oppose participation in war on the basis of their religious, moral, or ethical beliefs. Such objection can take many forms, such as refusing to serve in combat, register for the draft, pay taxes tied to war allocations, or make any type of contribution to a war effort.

Primary impetus for conscientious objection has been religion

Conscientious objection has a long history and is international in scope. The primary impetus has historically been religious.

Before the American Revolution, most conscientious objectors were members of “peace churches” — among them the Mennonites, Quakers, and Church of the Brethren — which practiced pacifism. Other religious groups, like Jehovah’s Witnesses, although not strictly pacifist, also refused to participate.

Governing authorities have dealt with conscientious objectors disparately, with some receiving exemptions and others being fined or imprisoned.

Alternative service allowed for religious-based conscientious objectors

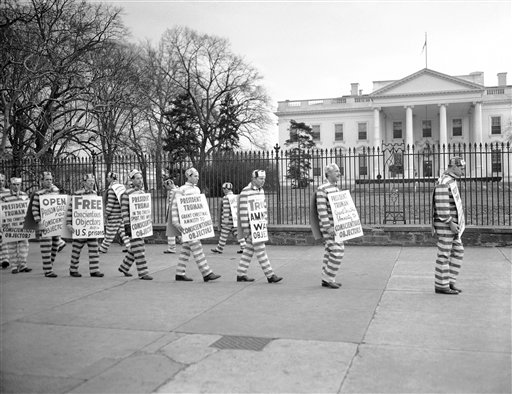

A group of sign-bearing demonstrators, clad in prison-garb, parade before the White House in Washington, Dec. 22, 1946, in connection with a campaign for the release from prison of conscientious objectors. (AP Photo, used with permission from The Associated Press)

During the Civil War, Congress enacted the nation’s first federal military conscription legislation, in which it provided exemption for anyone who paid a substantial fee. After riots and debates about the discriminatory nature of the fee exemption, Congress passed legislation allowing alternative service for members of the peace churches.

The alternative service option for religious objectors continued during World War I, but those conscientious objectors who based their beliefs on political, moral, or personal grounds were conscripted and punished if they refused to serve.

In World War II, the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 provided for mandatory alternative service for those who refused to take part in combat “by reason of religious training and belief.” Those who failed to meet these qualifications but refused nonetheless to participate were imprisoned.

Supreme Court decides conscientious objector cases in Vietnam War

The number of conscientious objectors numbered in the thousands during the Vietnam War, with many objectors, and others, viewing the conflict as an unjust war.

The Supreme Court was called on to interpret the exemption for conscientious objection and its relation to the First Amendment in Welsh v. United States (1970) and Gillette v. United States (1971).

Section 6(j) of the Military Selective Service Act of 1967 provided, “Nothing contained in this title . . . shall be construed to require any person to be subject to combatant training and service in the armed forces of the United States who, by reason of religious training and belief, is conscientiously opposed to participation in war in any form.”

In Welsh, the Court somewhat creatively interpreted and thereby broadened the phrase “by reason of religious training and belief.” According to the Court, “What is necessary . . . for a registrant’s conscientious objection to all war to be ‘religious’ within the meaning of 6(j) is that this opposition to war stem from the registrant’s moral, ethical, or religious beliefs about what is right and wrong and that these beliefs be held with the strength of traditional religious convictions.”

Today’s Selective Service guidelines state, “Beliefs which qualify a registrant for CO status may be religious in nature, but don’t have to be. Beliefs may be moral or ethical; however, a man’s reasons for not wanting to participate in a war must not be based on politics, expediency, or self-interest.”

Conscientious objection to military service refers to the position taken by individuals who oppose participation in war on the basis of their religious, moral, or ethical beliefs. Such objection can take many forms, such as refusing to serve in combat, register for the draft, pay taxes tied to war allocations, or make any type of contribution to a war effort. This Feb. 2, 1972, file photo shows Draft Director Curtis W. Tarr spinning one of the two Plexiglas drums in Washington as the fourth annual Selective Service lottery begins. (AP Photo/Charles W. Harrity, used with permission from the Associated Press)

In Gillette, Court reasoned objectors must oppose all wars, not only “unjust” wars

The Court in Gillette declined to provide additional relief to conscientious objectors to the Vietnam War.

Gillette had objected to participation in the Vietnam War and had refused induction, but he was not necessarily opposed to all wars. Gillette’s view of his duty was to abstain from any involvement in unjust wars. He alleged that if section 6(j) were construed to cover only objectors to all war, it would violate the religion clauses of the First Amendment.

The Court rejected that view and in the process made it clear that objection to a particular war, as opposed to war in any form, was an impermissible basis for asserting a claim of conscientious objection.

This article was originally published in 2009. Professor John H. Matheson is the Law Alumni Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Minnesota Law School. He is an internationally recognized expert in the area of corporate and business law. He is also a practicing lawyer.